It happened much as the critics had feared and without any headlines. Last December, a giant for-profit health insurance company pulled nearly $29 million of accumulated Oregon Health Plan profits and reserves out of Oregon, public records show.

OREGON'S MEDICAID BONANZA

This article is fourth in a series that delves into CCO finances.

Read the series:

Pandemic handed big profits to companies serving the Oregon Health Plan

Flush with profits, Oregon Health Plan insurers tell Kotek they need flexibility

Oregon Health Plan insurers propose spending $25 million to offset record profits

The funds had come from state and federal taxpayer spending on the program, which provides free health care for the poorest Oregonians. With state regulators’ approval, the Missouri-based company, Centene Corp., moved the money from its Lane County subsidiary to the coffers of the publicly traded parent company. That came atop nearly $6 million Centene had quietly pulled out its Oregon Health Plan operations a year earlier.

By contrast, more than a decade ago, when a group including then-Gov. John Kitzhaber spearheaded Oregon Health Plan reforms, they envisioned a system marked by local control in which profits would be reinvested in community health. Compromises were made, however, and efforts over the years to prevent Oregon Health Plan profits from being siphoned from the system — led by late state Rep. Mitch Greenlick and then-Speaker of the House, Rep. Tina Kotek — repeatedly stalled in the face of opposition by for-profit contractors to the program.

Since the launch of the new Oregon Health Plan system 12 years ago, the payouts, called dividend payments, have added up, a Lund Report analysis of financial statements shows. Nine regional Oregon Health Plan insurers, including Centene’s Oregon subsidiary, Trillium Community Health Plan, have paid out a total of more than $300 million in dividends to the companies that own them.

To put that in context, the state of Washington recently spent $30 million to buy a much-needed 100-bed behavioral health hospital.

In Oregon, $300 million is enough to pay for a year of free health care for 50,000 uninsured poor people — or the entire city of Tigard.

Now, the insurance contractors in the Oregon Health Plan have garnered massive profits and reserves during the pandemic, opening the door for them making further dividend payouts to owners. That puts the system at a turning point, some advocates and leaders say.

The state program has proven financially solid, but some fear a national trend of rapid consolidation in health care could erode its community-focused vision. They say it is time to stanch payouts by the regional care organizations to owners.

“It’s unfortunate to know so many dollars are leaving the state or leaving the communities,” said Dr. Bruce Goldberg, former director of the Oregon Health Authority, who was a primary author of the system approved in 2011. “The dollars were meant to stay in the community to improve the health of the community.”

“The dollars were meant to stay in the community to improve the health of the community.”

Kitzhaber told The Lund Report “it is important to revisit” the Oregon Health Plan to see how the program has evolved, including the model of “unique, community-based organizations” set up to administer it.

State Rep. Rob Nosse, D-Portland, said the payouts tallied by The Lund Report should “absolutely” be a focus of legislators and the Oregon Health Authority as the state begins a review of potential Oregon Health Plan reforms in 2024. Nosse chairs the House Interim Committee on Behavioral Health and Health Care. Of the $300 million that’s left the system, he said, “That’s a lot.”

Concerns over how the care organizations that administer the Oregon Health Plan spend their profits and reserves have also surfaced in the proposed merger of CareOregon, which provides care to 500,000 members of the plan. Under the proposal, CareOregon would ship as much as $120 million to a new merged entity based in California.

Dr. John Santa, a prominent Oregon health care leader who is opposing the deal, wrote in comments on the proposal, “Those assets are the community’s assets. They should be available for CareOregon’s members.”

Asked to comment on the issue, Eric Hunter, president and CEO of CareOregon, did not address whether the system needs reforms. But he defended the merger plan, saying $50 million of the funds that would be shifted to the new entity would be for reinvestment in Oregon to improve services.

A plan built on compromise

Oregon won federal Medicaid officials’ approval for the Oregon Health Plan in 1994. Spearheaded by Kitzhaber, the plan enlisted the cooperation of local physician groups — many organized as for-profit associations — to run the insurance system for low-income people in communities where no commercial insurer felt the work would be sufficiently profitable.

Starting in 2009, the state launched a redesign to improve accountability and ensure local control, cementing a system of what amounted to regional for-profit and nonprofit franchises. Called coordinated care organizations, they had to meet performance measures to receive state funding, offer coverage and oversee the provision of care.

Kitzhaber, an emergency room physician who began a second stint as governor in 2011, joined Goldberg and others in crafting the reforms that drew national acclaim.

The for-profit managed care organizations, however, fought off efforts by Greenlick, a pharmacist and health systems researcher, to require that organizations providing the Oregon Health Plan be nonprofits as a way to keep money in the community.

Still, the design was intended to enshrine local control, give community members and local health care providers a voice in spending and keep profits in the community, recalls Goldberg, who helped implement the reforms as director of the Oregon Health Authority from 2010 to 2014.

“That was clear, and there was a lot of general agreement among policy makers, providers, consumers, that that was a laudable goal,” he said. Coordinated care organizations, he said, were not intended to be “profit-generating machines. They were meant to put dollars back into the community.”

State regulators can’t stop it

But the final rules of the 2011 reforms left the care organizations latitude on how to use profits they accumulated.

Since then, expansion drives by several ambitious CCOs have pushed the Oregon program away from its original vision of local control. Centene has expanded from Lane County into Washington, Multnomah and Clackamas counties; CareOregon has moved into the Jackson and Tillamook regions; and Springfield-based PacificSource now operates coordinated care organizations in Lane and Marion counties, the Deschutes County area and the Columbia Gorge area.

Meanwhile, the rate at which owners have pulled dividends out of the system has accelerated even as state regulators have increasingly realized there’s little they can do to stop it.

Nearly a third of the dividend payments sent out of the program by care organizations over the last 11 years — $90 million — came in 2020-22.

A large chunk went to Centene through its control of Trillium, which receives taxpayer dollars to provide Oregon Health Plan insurance to 77,000 low-income residents in Lane County and the Portland metro area.

For years, Trillium was owned by a for-profit group of Lane County-area doctors, business people and other investors. Profits from the Oregon Health Plan business rolled in. Trillium stashed the money into its reserves.

In 2015, the local owners decided to sell the business to Centene. The owners paid themselves a dividend of $22 million from Trillium’s reserves, Trillium’s filings show. Then, the individual owners received $80 million from Centene as payment for the business, with the promise up to $50 million more, depending in part on Trillium’s financial performance.

Under Centene, Trillium’s Oregon Health Plan business has made a profit every year except one. Profits for 2016-2022 totaled $54 million, of which $47 million came during the pandemic. Trillium stashed the money into its reserves.

In 2021, records show, Trillium began pressing the health authority to approve dividend payouts. Centene wanted to pull as much of Trillium’s reserves and profits as legally possible and transfer them to the ownership of the parent company in St. Louis, state records reviewed by The Lund Report show.

Trillium’s first request, to send $71 million to Centene, ran into a wall of opposition from the Oregon Health Authority. Citing state rules that bar dividends from exceeding the total of the profits of the previous three years, the health authority denied the $71 million request, but eventually allowed a $5.8 million dividend for 2021.

In late 2022, Centene wanted more. By that time, with pandemic profits, Trillium had accumulated reserves of $106 million.

Trillium in August 2022 notified the Oregon Health Authority it wanted to ship a $28.9 million dividend payout to the parent. That triggered nearly three months of scrutiny by state regulators, who concluded they had no choice but to approve the payout, internal emails show.

“Under the OHA statutes, the dividend was deemed to be ordinary and OHA could not deny this distribution,” a health authority actuary, Rebecca Level, wrote to other agency staffers in December 2022.

Contacted for comment on the dividend payouts and Oregon Health Plan, Centene declined to respond.

Other owners take dividends

Dividend payouts vary widely from one care organization to another. And what the owners then do with that money varies or is undisclosed.

Some of the biggest dividend payouts have been made by the Eastern Oregon Coordinated Care Organization, which provides the Oregon Health Plan in 12 counties east of the Cascades and has paid its owners $72.5 million in dividends since 2016. Another big dividend payer is Umpqua Health Alliance, which provides the insurance in the Douglas County area and has paid its owners $66.6 million in dividends since 2014.

Umpqua is jointly owned by a Douglas County-based for-profit group of doctors and the nonprofit Mercy Medical Center in Roseburg. Eastern Oregon CCO is jointly owned by regional nonprofit health care providers and Moda Holdings Group, a Portland-based for-profit health insurer.

Umpqua’s leadership did not respond to a request for comment.

A spokesman for Moda said most of the $10 million in dividends the CCO paid out last year went to the local nonprofit healthcare providers that are part-owners.

“Several (Eastern Oregon CCO) owners provide comprehensive care to local residents, and often are the largest employer in their community,” the spokesperson said in an email. Dividend payments “thus allow for further local investment in healthcare access and workforce development,” he said.

Another entity that has withdrawn dividends from the system is the for-profit owner of AllCare, which is a certified benefit corporation, or “B corp.” Josh Balloch, a vice-president, says the $20 million withdrawn was spent on technology for the organization and was counted as dividends due to a state agency form that has since been corrected. He noted that at times, owners of the care organizations have also put money into the organizations to comply with the state’s reserve requirements.

It’s perfectly legal for the care organizations to pay dividends to owners, David Baden, interim director of the Oregon Health Authority, told The Lund Report.

“Dividends are going to be part of their business model, depending on their ownership structure,” he added, “I’m not saying on its surface that dividends are bad for the (CCO) model.”

“Trillium and Centene and their business model have a legal right to operate” in the Oregon Health Plan market, Baden added. “Our job is to ensure that they are delivering the services that they are contracted to do.”

Nor are all dividend payouts profit sharing.

Springfield-based nonprofit PacificSource Community Solutions, which consists of four CCOs in the south and central Willamette Valley, Central Oregon and the Columbia Gorge, paid $30 million in dividends to its parent nonprofit PacificSource, a multi-faceted nonprofit health insurance group, in 2022. That was a partial return of $80 million in capital that the parent nonprofit put into PacificSource Community Solutions in 2019-20, PacificSource told Oregon Health Authority regulators. PacificSource Community Solutions had needed the extra reserves because its membership had greatly expanded, and the health authority calculates reserve requirements partly based on a CCO’s membership size. By the tail end of the pandemic, PacificSource’s CCOs had accumulated such large profits that they could afford to make the repayment, PacificSource told the health authority. The agency approved the payout.

Quandary over program’s design

Most states use a form of privatized managed care, contracting with big insurance companies to operate their Medicaid systems. When Kitzhaber and Goldberg spearheaded the Oregon Health Plan reforms more than a decade ago, health care leaders around the state agreed that Oregon wanted something different and better than typical Medicaid managed care.

They tried to set up a community-oriented public-private partnership in which profits made off service delivery would reward innovation and efficiency and also be reinvested to improve people’s health and bring down the overall cost of care.

Rather than being mere insurance companies, leaders agreed, the regional coordinated care organizations approved by the state would be highly regulated entities in which providers and community members would have a say in how to meet performance outcomes set by the state.

But Greenlick, the pharmacist-lawmaker, fell short in the Legislature when he sought to require all the organizations be nonprofit.

Charlie Swanson of Eugene, president of the advocacy group Health Care for All Oregon-Action, told The Lund Report that’s where things went wrong. If the state had required all coordinated care organizations to be nonprofits “they could accumulate reserves, but they couldn’t run away with them,” he said. “The whole thing was designed wrong.”

Sparked by Centene’s acquisition of Trillium, Greenlick tried again in 2016 and 2017, seeking to keep profits made off the Oregon Health Plan invested in local communities.

But he ran into threats from the for-profits that they would shut down.

The legislation foundered, but not before Greenlick had enlisted an important co-sponsor — then-Speaker Kotek.

Now, she is one of only a few leaders still alive and in public service who participated in the Oregon Health Plan reforms.

Only a few states have moved away from the traditional Medicaid model — including Oklahoma in 2004 and Connecticut in 2012 — at times citing concerns that the major for-profit insurance companies ran up excessive operating costs and provided poor service.

But nobody has definitively studied states’ relative performance under the different systems.

“Beneficiaries, providers, and the public have a right to know how Medicaid dollars are being spent by organizations that are the stewards of healthcare for their enrollees.”

"The role of dividends in Medicaid is an issue on which reasonable people can disagree. That conversation starts with transparency about those dividends,” said Andy Schneider, a research professor at Georgetown University’s school of public policy, and formerly a Medicaid official in the Obama administration. “Beneficiaries, providers, and the public have a right to know how Medicaid dollars are being spent by organizations that are the stewards of healthcare for their enrollees.”

Time for a new look?

Leaders who worked on crafting the program more than a decade ago said the state left open the possibility of dividend-taking by care organization owners. It was a way to maintain participation of the local physician groups that had formed the regional entities that were vital to running the system.

Today, however, the system, with its 16 regional care organizations, is well established, and that financial incentive is no longer needed, said Martin Taylor, who worked on the legislation in 2011, when he served as an executive for one of Oregon’s largest coordinated care organizations, Portland-based CareOregon.

“We no longer have to make that compromise,” Taylor said in an interview with The Lund Report. “We can have a more principled approach in which the dollars would be protected for the public benefit.”

With Oregon seemingly moving closer to a universal health plan, Taylor believes the regional care organizations could be incorporated in that design — and now is the time where the system could be teed up for a transition.

Oregon's contracts with all the coordinated care organizations will lapse in 2026, and the Oregon Health Authority begins a formal re-contracting process next year. The state should use that opportunity to set new restrictions and stanch the flow of profits out of the system, Taylor said.

Kitzhaber and Goldberg, the pioneers who played a primary role in crafting the Oregon Health Plan system, agreed lawmakers and regulators should take up the issue of the program’s design as talks begin next year around potential revisions.

Kotek, asked to comment on whether the state should do more to keep its health care spending going to care, was noncommittal in a statement issued through a spokesperson.

“The Governor looks forward to public input to inform the goals of the next (CCO) procurement, and she will continue to focus on making sure tax dollars are focused on improving health outcomes for Oregonians,” it read. Kotek has a “long record of pushing for transparency and accountability” in the Oregon Health Plan, and “she continues to believe that CCOs must continually be held to a higher standard in service to their members, their immediate community, and the public.”

Balloch of AllCare, the for-profit coordinated care organization that serves the Grants Pass area, was also involved in the reforms more than a decade ago. The next system redesign could do more to keep money in the system, but not through top-down directives, he said. Rather, the rules could better reward community investment by coordinated care organizations, he said.

“It’s a question of incentives, not safeguards,” he said. “We’ve failed to really do a holistic approach of creating the incentive to reinvest back into the community.”

CCO DIVIDEND PAYOUT SNAPSHOTS

Financial summaries of CCOs that have paid dividends to owners.

PACIFICSOURCE COMMUNITY SOLUTIONS

Springfield-based non-profit covers 325,000 members in Lane, Marion and Polk counties and the Deschutes County and Columbia Gorge areas.

Part of non-profit PacificSource insurance conglomerate, which is 50% owned by Portland non-profit hospital system Legacy Health.

Financials:

Net assets/capital at end of 2022: $196 million, up from $108 million at end of 2019.

Total 2020-22 profits: $120 million on revenues of $5.1 billion; annual average profit margin of 2.4%. Profits were rolled into reserves/investments.

Dividends: Paid $30 million to parent company in 2022 as partial repayment of capital parent had put into PacificSource Community Solutions as it expanded into Marion and Lane counties. Also paid $30 million in dividends in 2016-17.

EASTERN OREGON CCO

Owned by a mix of for-profit and nonprofit entities. Covers 72,000 Medicaid members in 12 Eastern Oregon counties. Ownership structure: For-profit Portland-based Moda Holdings Group, 29%; nonprofit Greater Oregon Behavioral Health 29%; remaining 42% owned by St. Anthony Hospital; St. Alphonsus Hospital; Grande Ronde Hospital; Good Shepherd Health Care System; Yakima Farm Workers Clinic; Eastern Oregon Independent Practice Association.

Financials:

Net assets/capital at end of 2022: $55 million, up from $19 million at end of 2019.

Total 2020-22 profits: $52 million on $1.2 billion revenue; annual average profit 4.3%.

Paid dividends to owners in 2022: $10 million; Also, in 2016-2019 paid total of $62.5 million in dividends to owners.

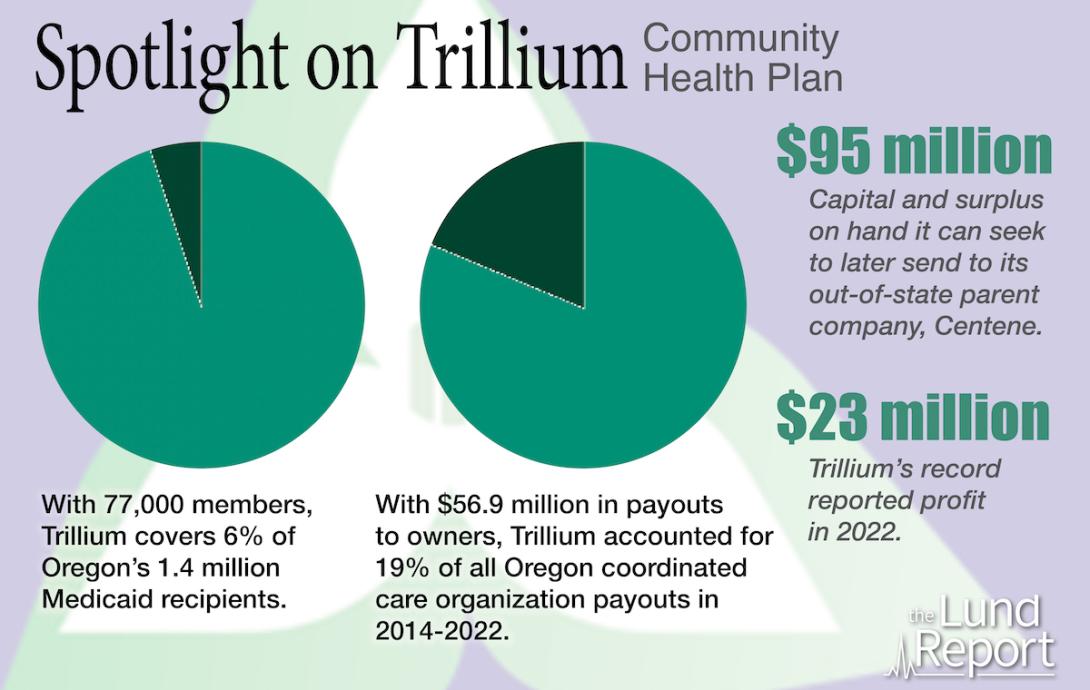

TRILLIUM COMMUNITY HEALTH PLAN

For-profit Springfield-based company covering 77,000 Medicaid members in two separate CCOs, one in Lane County, the other in the Portland metro area. Wholly owned by for-profit Centene Corp., based in St. Louis, Mo.

Financials:

Net assets/capital at end of 2022: $78 million, up from $70 million at end of 2019.

Total 2020-22 profits: $47.2 million on total revenue of $866 million.; 5.4% annual average profit margin.

Dividends paid to parent company: $28.9 million in 2022; $5.8 million in 2021; rest of profits rolled into reserves/investments. Prior dividends to previous owners: $22 million in 2015.

ALLCARE HEALTH

For-profit, doctor-owned, based in Grants Pass, serves 63,000 Medicaid members.

Financials:

Net assets/capital at end of 2022: $48 million, up from $18 million at end of 2019.

2020-22 financials: $29 million total profit on total revenue of $893 million; average 3.2% profit margin. No dividends paid to owners 2018-2022; profits rolled into reserves/investment portfolio. Dividends paid to ownership 2014-2017: $20 million, which the company says it spent on technology improvements for the CCO.

UMPQUA HEALTH ALLIANCE

Roseburg-based entity serving 38,000 Medicaid members in Douglas County.

Ownership structure: 50% by for-profit doctor group Douglas County Individual Practice Association; 50% by nonprofit Mercy Medical Center in Roseburg, part of non-profit CommonSpirit Health Catholic hospital system based in Denver.

Financials:

Net assets/capital at end of 2022: $36 million, up from $20 million at end of 2019.

Total 2020-22 profits: $30.2 million, on revenues of $573 million; average annual profit margin 5.2%.

Paid dividends to owners in 2020-22: $13.5 million ($2.3 million in 2022; $10 million in 2021; $1.2 million in 2020. Also paid dividends to owners totaling $53.1 million in 2014-19.

ADVANCED HEALTH

For-profit based in Coos Bay serving 27,000 members in Coos, Curry counties.

Owned by individual doctors, others.

Financials:

Net assets/capital at end of 2022: $11 million, up from $9 million at end of 2019.

Total 2020-22 profits: $3 million on $462 million revenues; average profit less than 1%.

Paid dividends to owners in 2020-22: $880,000 ($519,000 in 2022; $361,000 in 2021).

CASCADE HEALTH ALLIANCE

Klamath Falls-based for-profit/nonprofit mix serving 26,000 Medicaid members. Ownership structure: 33% owned by Sky Lakes Medical Center, rest owned by area doctors and other individuals or groups.

Financials:

Net assets/capital at end of 2022: $19 million, up from $9 million at end of 2019.

Total 2020-22 profits: $10 million on revenues of $366 million; average annual profit margin of 2.8%.

Paid dividends to owners in 2020-22: $500,000 in 2021; rest of profits rolled into reserves/investments. Also paid $9 million dividend in 2019.

You can reach Christian Wihtol at [email protected] and Nick Budnick at [email protected].

Comments

I do not understand why we…

I do not understand why we do not require CCO's to integrate behavioral health care into their primary care clinics. The continued segregation of behavioral healthcare and those who need it is a major disconnect. Some of what is labeled as profit may actually be dollars that should be spent proving BH care to all in primary care and primary care to all in the segregated BH care system.

Thank you, Lund report for…

Thank you, Lund report for delving into the complex financial and political mechanisms behind the CCOs and the payouts / dividends.

I genuinely don't see how this is different from the financial behavior of health insurers operating in the private market. For-profit insurance companies pay dividends to their shareholders too. I do think it's important to question why Oregon utilizes the CCO model at all though, when it has consistently failed to achieve progress on any of its original stated goals (lower costs, improved health outcomes, and increased healthcare accessibility/quality). The only noticeable impact the "local control" element has is increasing the ability of local healthcare companies to influence actual policy. Paying shareholder dividends to out-of-state insurers benefits the "local community" exactly as much as investing public funds on highly inefficient local monopolies.