Gov. Tina Kotek is getting an earful from insurers serving the Oregon Health Plan after challenging them to spend more on the communities they serve.

The 16 regional insurers, who are contracted to spend public funds for care of low-income Oregonians, last year enjoyed what state officials termed a “windfall” of profits, as first reported by The Lund Report.

Oregon's Medicaid Bonanza

This article is second in a series that delves into CCO finances. Read the first here.

In late June, Kotek and Oregon Health Authority officials asked the state’s Oregon Health Plan insurers to detail their spending on patients and communities, while describing what more they can invest in housing and behavioral health.

What Kotek and the health agency received instead amounts to a long list of what insurers portrayed as major defects in how the Oregon Health Authority oversees the system, records show.

The insurers, called coordinated care organizations, told the governor that the health authority should get rid of conflicting rules that stifle the insurers’ efforts to fund community-focused work.

The exchange between the state and the insurers — and what comes next — could serve as a litmus test for how Kotek’s administration will direct a program that spent more than $7 billion last year in federal and state money. More than a decade ago, Gov. John Kitzhaber spearheaded reforms intended to hold Oregon Health Plan insurers accountable while giving them leeway on how best to improve care. In recent years, however, the insurers complained that Gov. Kate Brown was too prescriptive.

The insurers’ responses, obtained through a public records request, included these complaints to Kotek:

- The health authority requires the insurers to hold excessive amounts in reserve, preventing them from spending it on services.

- Insurers’ spending on some innovations, such as paying for health care workforce training, is inappropriately categorized by the health authority as administrative work, putting the insurers at risk of violating state rules limiting how much they can spend on administration.

- State rules don’t give insurers discretion to spend on customized community-oriented projects that address a region’s specific needs.

Big pandemic profits

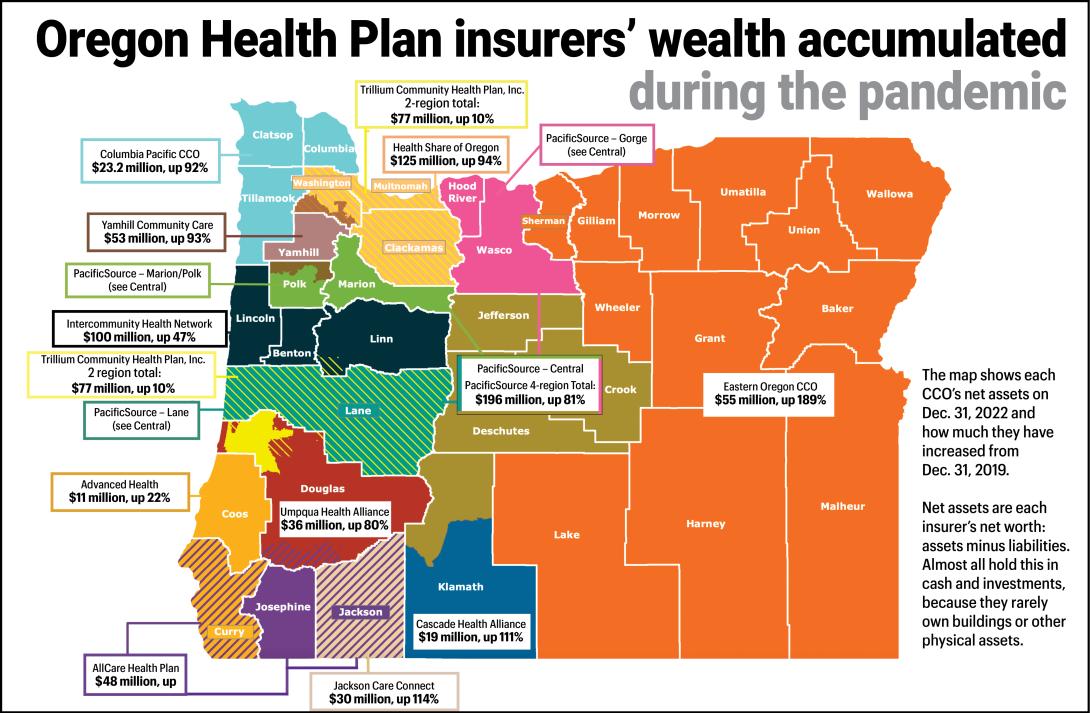

Kotek’s focus on the insurers is driven by the high profits and massive investment portfolios the companies accumulated during the pandemic.

The state issues five-year contracts to the regional insurers to oversee the spending of state and federal Medicaid funds on health care.

During the pandemic, while the insurers’ membership and revenues from the state grew, their spending on health care services was stagnant due to workforce shortages and pandemic-related restrictions at hospitals, clinics and other providers.

An analysis of financial filings by The Lund Report found that:

- From the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 to early 2023, the insurers serving the Oregon Health Plan collectively garnered profits of nearly $440 million.

- Some insurers’ profit margins topped 7% — well over the margin of close to 1% projected by state officials for the program.

- The Oregon Health Plan insurers’ combined profit margin of 4.6% in 2022 was well over a reported national average of 3.3%.

- Collectively, fed by the profits of the last three years, the 16 insurers at the end of 2022 held $833 million in net capital and retained profits, state calculations show. That’s nearly double the pre-pandemic amount.

In light of those profits, the health authority’s Interim Director Dave Baden informed the insurers in a June 29 letter that Kotek wants the coordinated care organizations to spend more on the community, particularly housing and behavioral health, and requested responses be directed to Kotek aide Abby Tibbs that included financial summaries, future plans and thoughts on whether the state’s reporting system properly captured the insurers’ investments in community health.

Baden suggested the regional insurers spend up to 2% of gross revenues in addition to their current spending on community-oriented projects. That would be equivalent to about $140 million a year.

Reserve concerns

In response to Baden’s letter, executives of the coordinated care organizations sounded off, some more sharply than others.

“The current regulatory structure creates conflict in how CCO dollars are spent,” wrote Eric Hunter, executive director of CareOregon, a Portland-based nonprofit health insurance company that operates regional coordinated care organizations in Jackson, Tillamook, Columbia, and Clatsop counties.

A project that CareOregon in Columbia County launched paid to improve the training and number of behavioral health workers in that region, but state officials ruled that was not a health related service and was instead an administrative expense, Hunter wrote. “This reinvestment clearly responds to community need but does not meet (health related service) criteria,” he wrote.

Another of the regional insurers, Advanced Health in Coos Bay, echoed that complaint. “We are cautious about over-committing to community investments when much of that work will necessarily be categorized as administrative,” the insurer wrote in an unsigned letter.

New state regulations in 2020 required Oregon Health Plan insurers to sharply increase the amount they hold in reserve, putting that money off limits to spending, wrote Josh Balloch, vice president of government affairs at AllCare Health, the coordinated care organization in the Medford area. Balloch urged the state to cut the reserve requirements for insurers that want to channel the money into community health projects. Several other insurer responses to Kotek echoed him.

The state wants the insurers to hold substantial reserves to cover expenses in case they go out of business. But just how much of their investment portfolios they can dip into without running afoul of state reserve requirements varies from insurer to insurer, and is sometimes unclear. Some coordinated care organizations appear to have investment portfolios that far exceed reserve requirements, while others have barely enough to meet mandated levels.

Insurers cite community spending

In their responses to Kotek and the health authority, the insurers stressed that they already have spent heavily on community-focused work. They reeled off scores of projects, from funding housing for low-income families and temporary shelters for the homeless, to paying for bus transit passes, funding cultural activities for non-English speakers, and improved training and recruitment of health care professionals.

And not all insurers complained about the state-imposed reserve requirements. PacificSource, the Springfield-based nonprofit health insurer that operates four Oregon coordinated care organizations that serve the Oregon Health Plan, noted in its response to Kotek that a new health authority regulation, which took effect last year, lets insurers put a portion of their required reserves into the development of housing for low-income families. PacificSource is working with the state to finalize procedures so that the insurer can channel money to Homes for Good, a Lane County nonprofit that develops and runs affordable housing in the county. PacificSource wrote that it “is actively seeking other housing agencies for similar arrangements in other regions.”

In their responses to Kotek, some insurers did not directly detail any specific plans they have for additional spending above the community-oriented work they already fund.

Advanced Health, the Oregon Health Plan insurer in the Coos Bay area, said its additional spending will depend on community needs and the region is in the midst of developing an updated community health improvement plan that won’t be ready until 2024.

The insurers also warned that while their profits ran unusually high during the pandemic, they are likely to drop in the next year or two. That’s because the state’s resumption of eligibility checks is expected to winnow several hundred thousand members from the Oregon Health Plan rolls. The remaining members generally are expected to have greater medical needs.

Also, the profits experienced by Oregon Health Plan insurers have fluctuated greatly over the years, wrote Sean Jessup, CEO of the Eastern Oregon Coordinated Care Organization.

In 2020-22, his organization made profits of $52 million on revenues of $1.2 billion, the Lund Report analysis found. But in the first five months of 2023, it had an operating loss of $2.8 million, Jessup wrote, adding, “This does provide an early indication that profitability will likely be significantly lower compared to the prior two years.”

This article is second in a series that delves into CCO finances. Read the first: “Pandemic handed big profits to companies serving the Oregon Health Plan”

This is what happens when services are privatized. Each privatization has its own details but they all result in private entities administering programs that should be run by government directly. The programs end up being more expensive and less accountable than public services. Oregon Medicaid used to be run by the state government until Gov. Kitzhaber handed control over to the private sector (mostly hospitals and insurance companies).