This article has been expanded to incorporate additional reporting.

During the pandemic, a bonanza of state and federal funds caused the net assets of a small nonprofit Medicaid health insurer called Yamhill County Community Care to balloon, jumping from $28 million to $58 million.

The money was supposed to be spent on the needs of 34,000 low-income Oregonians enrolled in the Oregon Health Plan and living in the insurer’s service area.

Oregon's Medicaid Bonanza

This article is the first in a series that delves into CCO finances.

But even as the monthly amounts received by the McMinnville nonprofit went up, up, up during the pandemic, members’ actual use of medical and behavioral health services sagged due to COVID-19 clampdowns.

The result: The insurer reaped record profits and finds itself sitting atop a mountain of cash.

And it’s not alone, sparking unprecedented questions for the state.

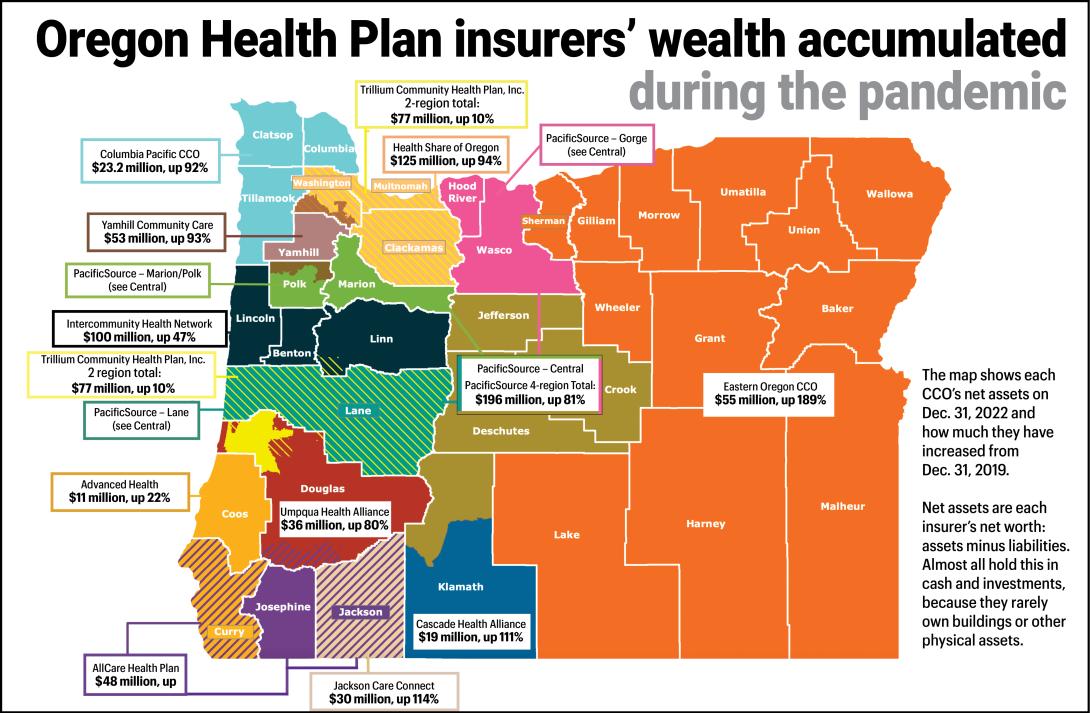

In all, the state contracts with 16 such regional health insurers to cover 1.5 million Oregonians on the Oregon Health Plan, the state’s version of Medicaid. Almost all those insurers had a similar scale of windfall revenues and profits during the pandemic, and for the same basic reason.

Before the pandemic, the insurers typically averaged annual profits just under 1%. But during the pandemic that leaped upward, to an average 4.6% by 2022, according to state data. That's well above what a consultant found was the national average of 3.3%

A Lund Report analysis of Oregon Health Plan insurers’ financial filings with the state found:

- Since the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 to early 2023, the insurers serving the Oregon Health Plan have collectively garnered profits of nearly $440 million.

- At their highest, in 2022, operating profits at some of the insurers, including Yamhill, topped 7%.

- Some of the insurers, including for-profit Springfield-based Trillium Community Health Plan and Roseburg-based Umpqua Health Alliance, which has a mix of for-profit and nonprofit owners, paid about $60 million of those profits out as dividends to their owners.

- But most of the insurers simply piled up the money in their reserves and investment portfolios, greatly increasing their net assets or net worth, which is essentially assets minus liabilities.

Collectively, fed by the profits of the last three years, the 16 insurers at the end of 2022 held $833 million in capital and retained profits — a measure akin to net worth — state calculations show. That’s nearly double the pre-pandemic amount.

What should the insurers do with that money? How or when should they spend it down for the benefit of members and health care providers? How much sway does the state have over that spending?

The insurers and the Oregon Health Authority have been quietly tussling over these questions for months, their correspondence and other records show.

In recent weeks, the state has upped the pressure, including telling the insurers’ CEOs that Gov. Tina Kotek wants to meet with them individually to talk about their profits and their plans.

Kotek to Oregon Health Plan insurers: Fund more housing and behavioral health

On May 30, the health authority’s interim director, Dave Baden, sent a letter to the insurers’ CEOs alerting them that The Lund Report had requested their financial filings under Oregon Public Records Law and that he envisioned a “holistic” discussion of the rules governing their spending and care.

“As you know,” Baden wrote, “financials show an increased net operating margin, gaining several percentage points since 2021. Please anticipate future engagement with the Governor’s office and me concerning current and future expectations to maximize Medicaid funds for member benefit.”

“With the influx of net income for 2022, the Governor wants to see a significant amount … committed to community reinvestment, with a specific focus on housing and behavioral health.”

In a follow-up email to the insurers on June 29, Baden went into more detail, telling them they’d be hearing from Kotek’s office about scheduling. “With the influx of net income for 2022, the Governor wants to see a significant amount … committed to community reinvestment, with a specific focus on housing and behavioral health,” he wrote. The amount Kotek has in mind: as much as 2% of their spending, or about $140 million a year.

A spokesperson for Kotek confirmed in an email that the governor intends to meet with the CEOs personally, adding that "the goal is greater overall health," including addressing the social factors or determinants that play into that.

"The Governor’s office recognized that the significant 2022 net income of Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organizations presented an opportunity to invest further in the communities that CCOs serve without undermining their financial sustainability."

Behind the windfall, funding up but usage down

Like many states, Oregon has long contracted with health insurers who receive state and federal Medicaid money to cover the health care costs of low-income residents.

In 2011, state lawmakers passed a law setting up a more formalized structure that divvies up billions of dollars of Medicaid funds among regional insurers — known as “coordinated care organizations,” or CCO. These companies enroll members, contract with health care providers, pay for member care and report to the state on their spending and progress in meeting health care performance benchmarks. Last year, the state paid them more than $7 billion in state and federal funds — by far the largest service that state government contracts out to private entities.

The pandemic windfall the CCOs enjoyed stemmed from federal and state policies. Normally, state officials regularly purge Oregon Health Plan rolls, booting out members who, for example, no longer qualify because their income has risen above the cutoff to qualify for the program.

But, like other states, Oregon halted that during the pandemic in keeping with a new federal rule that provided extra Medicaid funding to halt the eligibility checks. Oregon CCO member rolls ballooned, from less than 1.1 million to 1.5 million.

As the number of people enrolled grew, the health authority sent more and more money to the CCOs under its funding formulas based on per-member, per-month payments.

Yet, with restrictions by hospitals and other providers, including cutbacks on elective surgeries and in-person office visits, member use of health care fizzled. Not only that, but low provider reimbursements paid by the insurers made it hard to keep providers for some services — meaning CCOs faced additional challenges delivering care.

Decade-old reforms promised efficiencies

The state’s 2011 Oregon Health Plan reforms envisioned a public-private partnership with CCOs to cut waste while improving care. But despite years of wrangling among CCO leaders, state officials and legislators, views continue to differ over how the state should regulate the regional insurers’ finances, including profits and reserve amounts.

Oregon’s funding of CCOs “is not a perfectly designed system, and there are ebbs and flows,” said John McConnell, director of the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

“Maybe the good part is that CCOs survived (the pandemic). But there’s discomfort when you see a lot of taxpayer money sitting in (CCO) reserves. We don’t see what it’s going toward.”

“Maybe the good part is that CCOs survived (the pandemic). But there’s discomfort when you see a lot of taxpayer money sitting in (CCO) reserves. We don’t see what it’s going toward,” McConnell told The Lund Report.

McConnell is particularly unnerved when CCOs use profits from their Oregon Health Plan operations to pay dividends to their out-of-state or for-profit owners. “That’s where there’s a seedy element to it,” he said.

Unlike in many states, most CCOs in Oregon are owned by Oregon-based entities, the majority of them nonprofits. Only a single medium-sized CCO — Trillium — is owned by a large out-of-state for-profit insurer, St. Louis, Mo.-based Centene Corp.

But CCOs in Oregon have something in common with their large for-profit corporate counterparts that dominate the national market, McConnell said.

The big corporations "all made tons and tons of money, so the Oregon (CCOs) are mirroring that," McConnell said.

A new report by Seattle-based health care consultant Milliman Inc. found net profits soared at Medicaid insurers nationwide, to 3% in 2020, 3.5% in 2021 and 3.3% in 2022, from under 1% in 2018 and 2019.

A handful of dominant, large for-profit insurance corporations that work for state Medicaid programs around the country reaped record revenues and profits from that work during the pandemic, their disclosures with the federal Securities & Exchange Commission show.

Andy Schneider, a research professor at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, has been drawing attention since mid-2020 to Medicaid insurers’ swelling pandemic profits and some states’ efforts to channel that money into member health.

“The industry, whether for-profit or not-for-profit, they are not really interested” in further state restrictions on profits, he told The Lund Report.

The industry’s net profit margin nationwide as reported by Milliman, about 3.3% in 2022, might not seem particularly high. But that margin is on a massive amount of revenue, $276 billion dollars nationwide, according to the Milliman report, Schneider noted to The Lund Report.

“They can leave (the Medicaid market) if they are not happy about the rates, but as far as I can tell we are not close to that point,” he said.

“Unjustified windfall” predicted

Even in the first year of the pandemic, state officials recognized the Oregon Health Plan had a problem because CCOs were not spending enough on care, potentially violating federal rules, according to a recent report submitted to the federal government obtained by The Lund Report.

“The state was facing a situation where CCOs were set to reap an unjustified windfall at a time when provider payments were cratering,” according to the report. “The state also wanted to support Medicaid providers in their time of need with sufficient revenue to keep their doors open and ensure ongoing access for OHP members.”

But the agency’s efforts to increase CCO spending — by amending the contracts to allow greater spending flexibility in 2020 — achieved only limited success.

So the profits pulled in by most CCOs during the pandemic only grew. In 2022, they collectively hit their highest profitability rate since 2015, according to state data.

Between them, the 16 insurers reaped $394 million in profits in 2020-2022, The Lund Report’s analysis of their financial filings show. That’s three times higher than their average pre-pandemic levels. The bounty continued into 2023. In the first quarter of this year, even with the pandemic fading, the CCOs reaped an additional collective profit of $44 million, on a par with their profit a year earlier.

Money stays “in the community,” insurers say

Like most insurers contacted by The Lund Report for this article, the leaders of Yamhill County Community Care did not offer any detailed plans for how its big surplus will be used to benefit community members.

“All resources — including surplus funds — remain in the community.”

“All resources — including surplus funds — remain in the community,” said Dan Cushing, the CCO’s government affairs director, in response to an inquiry from The Lund Report. The money will go to “community benefit initiatives, grants to community-based organizations, and other investments aligned with our mission, vision, and values and at the direction of our local board of directors,” he wrote in an email.

Some CCO representatives told The Lund Report they are voluntarily planning to put some of their windfall into special health projects.

Others favor keeping their money in reserve to cover a possible sharp post-pandemic rise in medical outlays as members seek long-delayed care. Indeed, state regulations recently changed to recommend much higher levels of reserves.

Some say the health authority’s resumption of eligibility checks on Oregon Health Plan members may have the effect of removing healthier, younger adults from the program, leaving CCOs to care for a core membership of older, sicker, marginalized and very low income people who are much more costly to cover.

State wants answers

In an interview, Baden, interim director of the Oregon Health Authority, said he wants all CCOs to explain their plans for the profits and reserves they accumulated during the pandemic.

CCOs need to show they have “a strategy for how that (money) is benefitting Medicaid members on a daily basis,” Baden told The Lund Report.

“I really do want to understand the CCOs’ plans (for that money) and assuring that these dollars are effectively going to better population health, building better systems of care, helping providers that are struggling. There are a lot of different things that these dollars could benefit,” he said. He declined to elaborate on how he might pressure the CCOs.

In his June 30 email to CCOs, he asked them to spell out all their ongoing and planned “community reinvestment initiatives” and other projects.

Insurers feel pushed, pulled

Despite their recent big profits, several CCOs complain that the state has been increasingly and unreasonably squeezing them with financial restrictions. Citing the program’s history as a partnership based on cooperation, some of them say an over-regulatory approach will hurt care.

New state rules that took effect in 2020 require CCOs to keep larger amounts of cash in reserve to cover emergencies or a CCO's sudden closure. Those rules also urge — but don’t mandate — CCOs to keep additional amounts of cash in reserve. Yet the state also prods CCOs to spend more on special community-oriented projects to improve member health. And it wants the insurers to cut the amount they spend on administrative costs or keep as profits.

Cascade Health Alliance, the Klamath Falls-area CCO that has for-profit and nonprofit owners, pushed back against a recent health authority proposal to tamp down on how much CCOs can spend on administration and take in profit. The state’s proposal “appears to remove any and all potential profits from CCOs,” leaving them in a position where they “are only able to break even or have losses,” wrote Cascade Health CFO Dawna Oksen. In the face of this and similar objections from other CCOs, the state dropped its idea of tightening what is called the "medical loss ratio."

Yet on the flip side, some CCOs say they expect continued good profits.

In Douglas County, the Umpqua Health Alliance, which is owned by a for-profit local doctor group and Roseburg’s nonprofit Mercy Medical Center, “is experiencing and expects to finish with another strong financial performance in 2023,” the insurer wrote in the annual management report it filed with the National Association of Insurance Commissioners earlier this year.

Umpqua Health’s profits for the first quarter of 2023 were $2 million, up from $1.2 million the year-earlier quarter, according to its latest filing. The CCO did not respond to requests for comment from The Lund Report.

Some CCOs say the state’s rules on their reserves make it seem like they are sitting on piles of cash, but don’t let them spend it on care. The state tightened the reserve requirements with "risk-based capital" rules in 2020.

“They are encouraging us to lock up more dollars and not invest more on (health services),” said Josh Balloch, vice president of government affairs at AllCare Health, the doctor-owned for-profit CCO that covers the Medford area. An insurer’s top priority is to pay health care providers for services, he noted. Left-over dollars can then be spent on social problems that affect health, Balloch told The Lund Report. But the state’s new"risk-based capital" rules have the effect of limiting that extra spending, he said.

AllCare, for example, held onto its strong 2020-22 profits of $29 million, putting them into its investment portfolio. That pushed AllCare’s net capital to $48 million by the end of 2022, double its pre-pandemic amount. Under the state’s rules, it must designate about $10 million of that as a reserve. But, to comply fully with the state’s "risk-based capital" guidance, it would need to hold a further $20 million in reserves.

Balloch said AllCare hasn’t decided how it will handle its surplus capital. But he fears the organization will incur big bills in coming months as the resumption of eligibility checks cuts Oregon Health Plan membership rolls back to roughly their pre-pandemic levels. That may leave CCOs with members who have unusually costly medical needs, Balloch said.

Baden, at the Oregon Health Authority, is sympathetic to that concern. The insurers need to be ready “for what is going to be a potential downturn” as a result of the eligibility checks, he said.

One of the state’s biggest CCOs, Springfield-based nonprofit PacificSource Community Solutions, has $196 million in net capital. But almost all of that is tied up meeting state-mandated reserves and the additional recommended reserves, said spokesman Lee Dawson. That’s because the larger a CCOs membership, the more it must set aside in reserves. PacificSource has 325,000 members in the Willamette Valley, Central Oregon and Columbia Gorge area. Compared to many smaller CCOs, PacificSource had a low profit margin in 2020-22: 2.4%.

McConnell said one positive of Oregon’s system is that most of its CCOs are Oregon-based nonprofits. So, if they eventually spend their saved-up profits, it will likely be on such things as new services for patients or higher payment rates to health care providers, he said.

At CareOregon, a Portland nonprofit that performs most of the Medicaid member management work for CCO Health Share of Oregon — while operating two smaller CCOs — profits and reserves swelled during the pandemic. Health Share, which is the official CCO for the 434,000 Portland metro area Medicaid members, had scant profits during the pandemic. But CareOregon reaped profits totalling $228 million from its work for Health Share in 2020-22, filings show. The profit margin averaged 7%. By the end of 2022, CareOregon’s net assets hit nearly $711 million, filings show, nearly double the pre-pandemic number.

As a nonprofit, CareOregon plans to spend its wealth on health care-related projects, said Jeremiah Rigsby, CareOregon’s chief of staff.

“The money has no place to go but back into the community,” he told The Lund Report. “That doesn’t mean it goes all at once.”

As the manager of a clinic with a 90% Medicaid patient population, this absolutely sickens me! CCO's - who are mandated to provide care to our most vulnerable citizens - are stealing from taxpayers to line their own pockets. Providers who actually care for patients are paid well below the cost of actually providing the care due to inflation, staffing issues, and an increased demand for services not always covered by OHP. Having a small amount in the bank to leverage against potential future costs? OK. Why are CCO's allowed unlimited dollars in this bucket (or to pay them out to 'investors') without having to actually pay it out to those who do the work? Quality measure 'payouts' are increasingly difficult to reach and those earned are but a fraction of these profit numbers. With fewer and fewer providers willing to stay in this market, how can those of us left continue meeting the demands of a larger patient population with decreasing reimbursement? Answer: They can't. Then what happens to these patients?