This article has been updated with Kotek's formal response issued hours after publication.

Under pressure from the Kotek administration to spend down the record profits they reaped during the pandemic, the insurers that the state pays to serve low-income Oregonians are offering $25 million toward a Kotek priority: behavioral health staffing and funding for facilities around the state.

The proposal by the insurers, who are contracted to oversee services for the Oregon Health Plan, is the latest development in a behind-the-scenes debate. At issue? How they should spend the taxpayer money that has swelled their coffers during the pandemic.

Oregon's Medicaid Bonanza

This article is third in a series that delves into CCO finances.

Read the series:

Pandemic handed big profits to companies serving the Oregon Health Plan

Flush with profits, Oregon Health Plan insurers tell Kotek they need flexibility

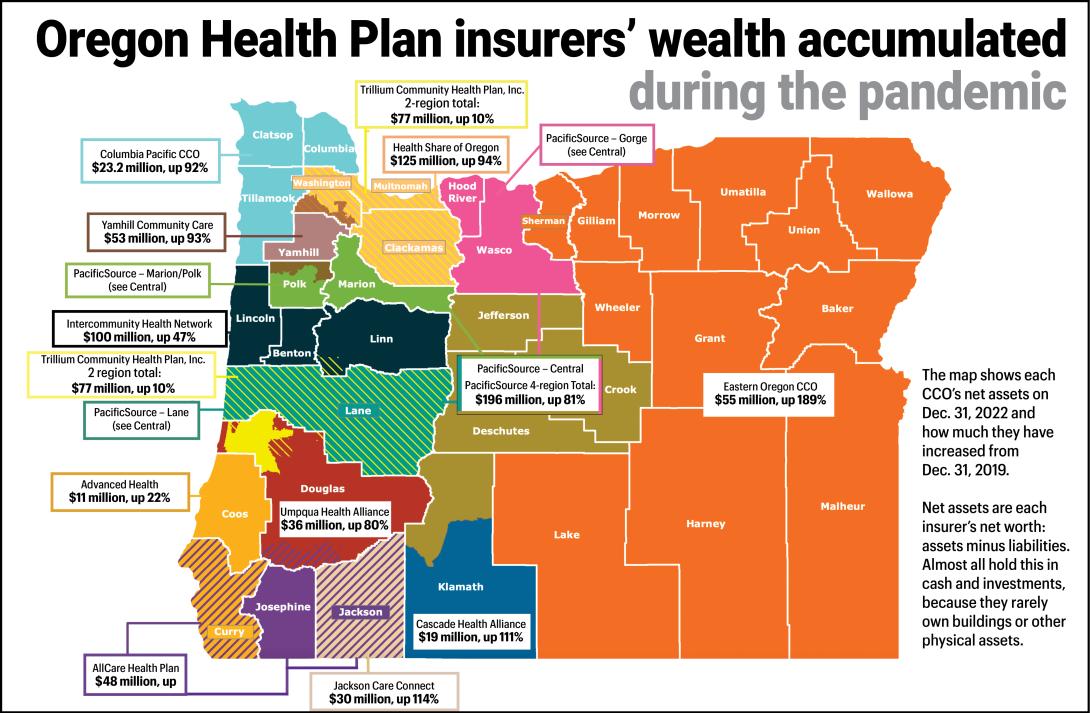

The $25 million amounts to a tiny slice of what an analysis by The Lund Report in July found to be the nearly $440 million in profits the insurers reaped from the onset of the pandemic to early 2023.

Like many states, Oregon has privatized its version of the federal Medicaid program, which serves 1.3 million people living in households earning no more than 138% of federal poverty level. That’s a little more than $20,000 annually for one person, or $41,400 for a family of four.

In the program, the state hands over a per-member monthly payment to insurers who in turn reimburse provider networks who care for Oregon Health Plan members. The insurers operate 16 regional coordinated care organizations around the state that have to report on metrics addressing access and quality of care as well as their members’ health.

The state pays the coordinated care organizations, or CCOs, roughly $7 billion a year to provide care. During the pandemic, members’ use of health care services dropped even as state payments to the insurers rose. The result: The organizations reaped record profits, which they mostly salted away into their reserves.

Before the pandemic, the state plan’s insurers typically averaged annual profits just under 1%. But during the pandemic that margin leaped upward, to an average 4.6% by 2022, according to state data. That’s well above what one consultant found was a national average of 3.3%.

That boosted their collective net worth – the value of all their assets, such as reserves, minus all liabilities – to $833 million.

Kotek gets involved

On May 30, the Oregon Health Authority’s interim director, Dave Baden, sent the CEOs of the insurers an email alerting them that The Lund Report had been requesting their financial reports. He asked them to turn in additional information about their spending, and notified them that Gov. Tina Kotek wanted to talk to them about their profits and investments in the community.

The CEOs met with Kotek on Aug. 10, and she asked them to promptly spend $25 million on behavioral health, given the high need for these services, according to a Sept. 1 memo they sent her that The Lund Report obtained under Oregon Public Records Law.

The proposal documented in the memo listed several projects. But the memo said that some of the insurers and their board members had “reservations” about being directed by the governor on how to spend their money. The letter said “engaging local providers, members and the broader community” is the best way to pick projects to serve Oregon Health Plan members.

Customarily, the Oregon Health Authority, community representatives and CCO management set CCO spending priorities. But the insurers have broad leeway on the specifics of how they spend their funds, including on special projects to address community needs.

The $25 million that Kotek urged the insurers to spend is for work on top of that.

For the most part, the spending laid out in the Sept. 1 memo would go to help projects already being pursued by nonprofits or health care agencies:

$2 million for Community Counseling Solutions in Boardman, as part of a project to build a proposed 14-bed psychiatric facility for children from around the state. An architect is working on construction plans. “This funding will speed the project toward completion, and benefit the behavioral health needs of children under 12, statewide,” said Tracy Forsyth, a spokesperson for Health Share.

$2.3 million for staffing costs to add 4 psychiatric beds at a Eugene facility run by nonprofit Looking Glass. The staff could be hired this fall. The money should staff those beds for a year, although payments from the Oregon Health Plan for services at the facility would likely extend that, Forsyth said.

$15 million for Trillium Family Services as part of a project to add 12 beds to The Parry Center in Portland, which serves youth with psychiatric needs. Additional money is needed to add those beds.

$7.5 million for Adapt in Roseburg as part of a project to add up to 77 beds for adult and youth detoxing and other substance use disorder treatment. Groundbreaking for some units is scheduled for this fall.

Under the proposal — which was unsigned — the $25 million would come from all the state’s CCOs in proportion to the number of members they insure. For instance, Health Share of Oregon, which covers the Portland metro area, would pay $8.4 million. Springfield-based PacificSource Community Solutions, which covers Lane and Marion counties along with the Deschutes area and the Columbia Gorge, would pay $6.2 million.

But the insurers’ memo stressed the state’s behavioral health care problems are far more serious than their proposal can address. The $25 million would only partly fund the ongoing projects, and more money is needed to “fully fund the proposed projects,” they wrote.

They called on Kotek “to convene a statewide conversation about the workforce and capacity needs of the behavioral health system and to leverage multi-stakeholder strategies.” They also urged Kotek to find public funds and “matching dollars from private insurers or other sources,” for the work.

Also, Forsyth said CCOs have asked the state for additional money to complete the Parry and Adapt projects.

“We are waiting on feedback from the governor’s office, which we expect shortly,” she said, adding that CCOs “welcome the opportunity to discuss project implementation timelines and further project details with the governor and her staff.”

On the afternoon of Sept. 25, Kotek issued a formal response to the insurers, saying she had heard their concerns about state rules that they say deter insurers from investing more in their communities and don't let some of that spending count as member care. She promised to continue discussing opportunities for improvement.

“As stewards of public funds, our responsibility to maximize Medicaid funds for member benefit must remain at the center of our work,” she wrote. “It is my expectation that CCOs will continuously improve member access to care and have a clear strategy for reinvesting profits. Reinvestment must continue to occur regardless of whether spending 'counts.'”

Records show the CCO’s profitability has continued into 2023. Of the state’s 16 regional coordinated care organizations, 11 reported net profits and five reported net losses for the first six months of this year. For the first half of this year, they collectively reported profits totaling $36 million.

Allocating additional spending to Behavioral Health is needed - but there continues to be a deep shortage of providers in this area. Allocating BH provider training to 'administrative expense' rather than considering it 'healthcare expense' will not help us increase the amount of available services to our community. Instead, BH patient needs continue to grow exponentially while those available to serve grow at a shockingly slow rate. In the meantime, the BH bucket of state money will stay where it is while patients are denied care in other areas due to a lack of funding. If all OHA cares about is numbers, why aren't they solving this simple algebra problem?