Seamus McCarthy, CEO and president of Yamhill Community Care, is still proud of the $1 million that the regional health care nonprofit spent eight years ago, equipping kids with skills that would help them later in life.

This article is part of an investigative series showing that as Oregon kids face a world with increasingly dangerous drugs and unparalleled external pressures, the state’s education establishment has failed to adapt.

The nonprofit started spending the money eight years ago to buy a new curriculum and train teachers at three schools in the county. And it’s since spread and paid off.

“Kids who have gone through this intervention in elementary school now, as adults, are having less incidence of chronic diseases like high blood pressure, heart issues, diabetes, etc,” McCarthy said.

The program, called PAX Good Behavior Game, is also shown to help with preventing addiction and substance abuse later in life, said Anthony Biglan, a prevention scientist at the Oregon Research Institute who was consulted by Yamhill about it.

The story is relevant because it comes at a time when Oregon and other western states are battling a drug crisis and escalating youth overdose numbers. An investigation led by The Lund Report found that school districts around the state are struggling to meet state-law requirements that they provide an up-to-date substance-use prevention program backed by research. As part of that project, reporting from the Oregon Catalyst Journalism Project found that state agencies provide Oregon’s school districts with little support or accountability.

However, McCarthy’s story shows how some school districts have found other sources of support. Yamhill Community Care is one 16 insurer-like entities paid by the state to oversee care for low-income members of the Oregon Health Plan.

All 16 are funded with state and federal Medicaid dollars. They are obligated to provide health care to Oregon Health Plan members but also to spend on additional initiatives to boost health in the communities they serve, such as prevention.

Yamhill is hardly the only such organization to invest in school-based programs to improve health. But Biglan said that if more go that route, “It is one way that prevention could be increased.”

Indirect effects

The PAX Good Behavior Game program is not a substance-use-prevention program. It doesn’t talk about drugs.

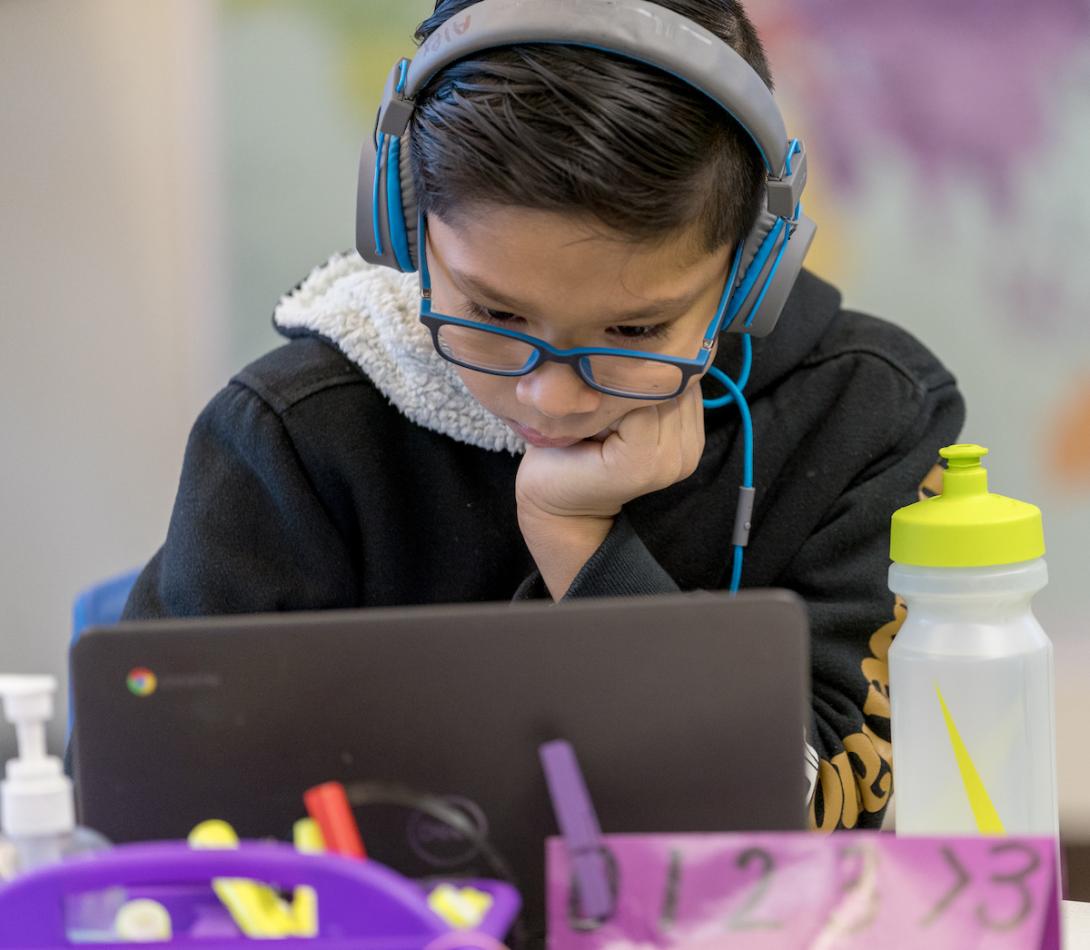

What it does is help kids regulate their own emotions and impulses, traits that can lead to long-term mental and physical health. And it also helps them in school.

The Yamhill program started with a small number of teachers in just three elementary schools, Biglan recalled. But pretty soon the feedback was, he said, “‘No, we want this for all the teachers.’ So the next year, we expanded it, but it also got expanded to other districts, and that was largely word of mouth. There was a demand for it.”

Yamhill was not the first place where one of the Oregon Health Plan organizations invested in schools.

In 2013, Trillium Community Health Plan launched a PAX Good Behavior Game initiative that it tried to spread throughout Lane County, part of nearly $1 million in overall spending on youth. A spokesperson for Trillium, which changed ownership in 2015, did not respond to several requests for information on its work on the initiative.

In 2015, AllCare Health launched a similar initiative that promptly spread to 10 out of 11 school districts in Jackson and Josephine County over the next two years. Josh Balloch of AllCare told The Lund Report his organization spent more than $600,000 helping schools adopt the program, not including additional support by community investment teams.

But he said that challenges negotiating Oregon Health Plan rules, combined with the pandemic, caused his group to transfer the PAX Good Behavior Game to the Southern Oregon Educational Services District.

Several of the regional care organizations told The Lund Report they are spending not just on schools, but on early childhood development efforts that they think could provide at least as big a benefit as substance-use prevention.

Becca Thomsen, a spokesperson for CareOregon, which operates two of the care organizations and serves the greater Portland region as well, told The Lund Report that her organization has been devoting its efforts to increasing connections between school staff and behavioral health providers, such as by funding yearly summits called “Behavioral Health in Schools.”

Last year, 176 people attended a four-part “learning series” hosted by the group for people who work with youth ages 12-17. The goal, Thomsen said, was to “increase access to treatment and knowledge of best-practices and supports for youth across the tri-county metro region by sharing clinical and community-based, evidence-based practices and interventions across the physical health, behavioral health, family, school and community settings.”

PacificSource, which operates four of the 16 regional Oregon Health Plan groups, has invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in vaping and overdose prevention, as well as binge drinking prevention for young adults.

Biglan, the researcher, said all of the Oregon Health Plan organizations would benefit from investing in school-based prevention programs that help curb anti-social behavior and risk factors for substance use disorders and other disease.

The responsibility of the organizations, he said, “is the health of the population that they serve. And the health of the population that they serve will be enhanced by these kinds of family and school interventions and community interventions.”