As science teacher Zach Lazar looks out across his classroom at South Eugene High School, he sees more kids struggling than he did before the pandemic. In the past two years, Lazar said, three of his students have died from drug use.

“It makes me sad to see how easy it is for students to go down the wrong path,” Lazar said. “I feel like it’s gotten worse, substantially, since we came back from online learning.”

This article is part of an investigative series showing that as Oregon kids face a world with increasingly dangerous drugs and unparalleled external pressures, the state’s education establishment has failed to adapt.

Lazar’s experience aligns with alarming trends: The rate of substance use disorder among Oregon youth ranks third in the country, and in the past six years, 348 Oregonians aged 15 to 24 died from accidental drug overdose. That’s enough to fill more than 15 high school classrooms.

In no other state have overdoses among teens aged 15 to 19 grown faster over the same time period, according to not-yet-finalized federal data. Now, a six-month investigation by The Lund Report in collaboration with the University of Oregon’s Catalyst Journalism Project and Oregon Public Broadcasting shows that a key institution — the state’s K-12 public school system — has failed to adapt to the new reality facing Oregon’s kids.

Oregon law requires administrators of every public school district in Oregon to have a robust substance use prevention strategy based on research. And studies suggest that well-crafted prevention programs can save tax dollars and young lives.

For this project, reporters asked the state’s 197 public school districts what they are doing to prevent substance use among their students. Districts teaching nearly 9 out of 10 of Oregon’s public school students responded.

The results show that most Oregon kids — living in a world with increasingly dangerous drugs and unparalleled external pressures — aren’t getting evidence-backed substance use prevention. That’s judging by the reviews of well-respected expert clearinghouses consulted with for this project. They examine prevention programs and curricula to determine whether they have strong scientific backing.

Among the findings:

- 60% of Oregon’s school districts don’t use prevention curricula or programs at any grade level that meet even the lowest bar for evidence, including Portland Public Schools, according to the nation’s top prevention and curricula clearinghouses.

- District responses showed 20% of districts rely on little more than a chapter in a health textbook to get the job of addiction prevention done.

- Though prevention experts emphasize starting substance use prevention early, only 44 of the 119 districts surveyed use programming endorsed by an expert clearinghouse’s evidence review at the elementary school level.

- Only one of the responding districts offers an evidence-based program that involves parents — which experts call a powerful component of effective prevention.

- Oregon’s school districts receive little support and guidance from the state to select substance use prevention programs backed by evidence.

- Other states follow the science, helping schools adopt evidence-backed programs.

A publicly accessible data portal details the results of the statewide inquiry reporters conducted, linking each responding Oregon school district’s prevention program with ratings and evidence reviews.

The data comes with caveats. Among them: Reviews of individual curricula may be incomplete or not done in a timely manner, and prevention science has limitations.

clearinghouses

The Lund Report consulted the following expert clearinghouses:

Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development at the University of Colorado Boulder.

CrimeSolutions at the National Institute of Justice. It focuses on reducing criminal behavior.

What Works Clearinghouse is housed within the U.S. Department of Education. It focuses on educational outcomes.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning evaluates and recommends social emotional learning programs.

These clearinghouses critically appraise the scientific credibility of evidence surrounding prevention methods.

But local experts say this project’s findings show that the state’s leaders could — and should — be doing more to improve the trajectory of young Oregonians.

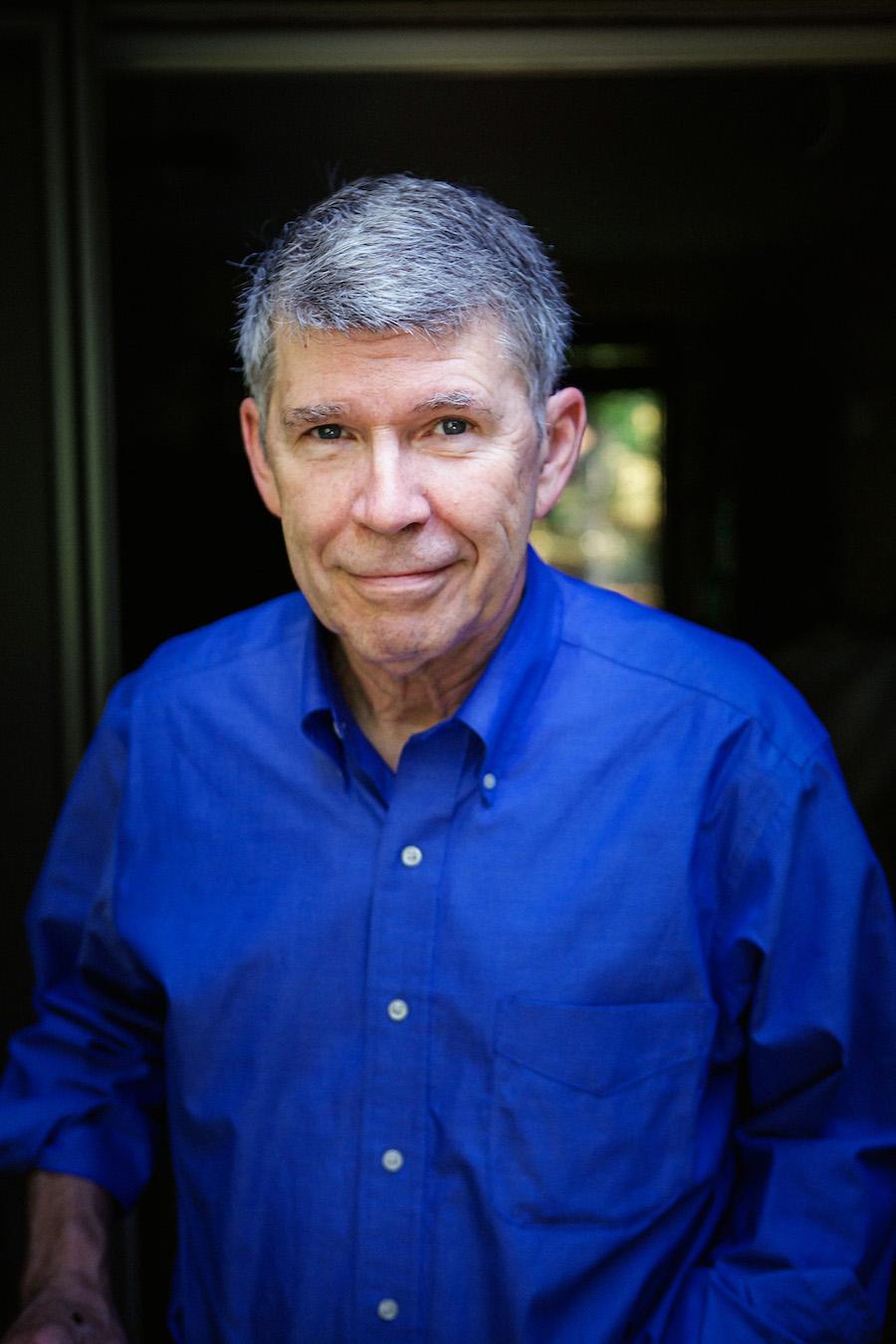

“These are dire findings and extremely important,” Mark Van Ryzin, a research professor who studies prevention at the University of Oregon’s College of Education, told The Lund Report.

Anthony Biglan, a senior scientist at the Oregon Research Institute said that if acted upon, the findings “could make an enormous difference.”

Gov. Tina Kotek vowed to take action. “These findings are alarming,” she said through a spokesperson. “I pledge to bring key agency leaders together to review these findings and develop a specific action plan to address these gaps. Prevention is part of the solution to Oregon’s addiction crisis.”

The good news? Some schools and educators are showing that evidence-backed prevention in Oregon is possible.

Across the state, 8% of districts have put in place curricula and programs that, according to expert clearinghouses, have the potential to reduce risk factors for addiction, across both their primary and secondary schools.

Still, Oregon’s youth live in a world where drugs are easily accessible through social media and can cost less than a dollar a dose. They are also growing up in the only state to decriminalize possession of hard drugs. The long-term effects of that change on teenage perceptions of drug-use harms and social norms is yet to be seen, as was underscored in interviews with students.

“We are at war in prevention, with big pharma, big tobacco, big alcohol, now big marijuana and drug cartels out of Mexico,” said Rodney Wambeam, a prevention scientist out of the University of Wyoming who’s conducted prevention work in about 40 of the 50 states. “And they are better funded.”

How Linn County brings an evidence-based program into classrooms

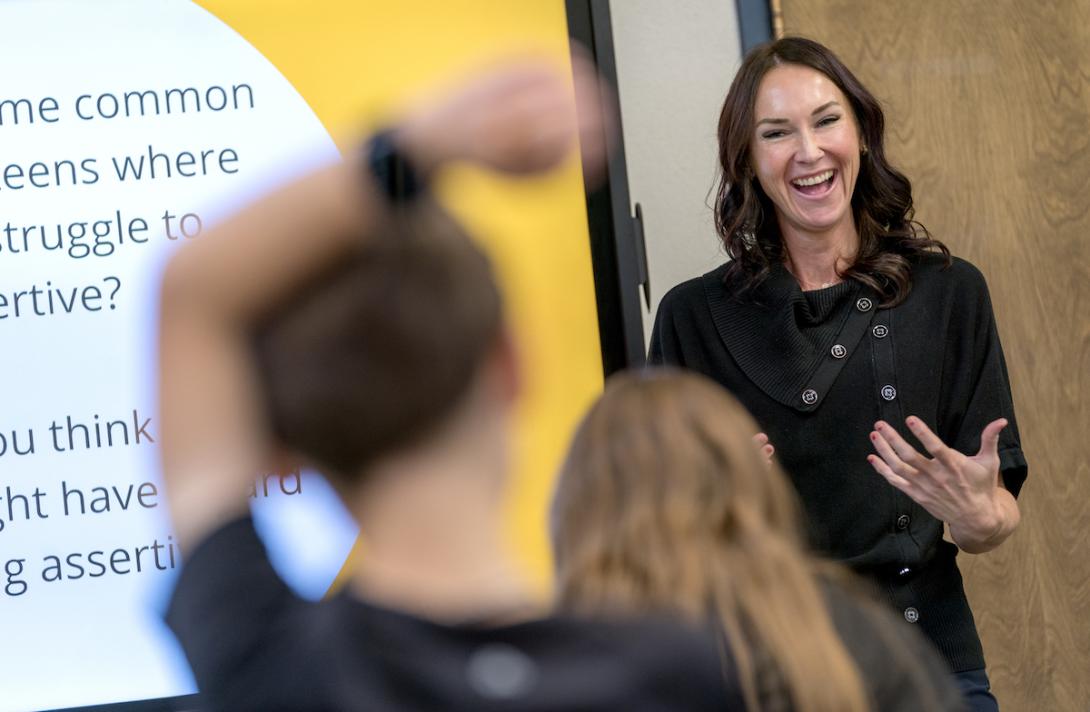

“Do you guys know what it means to be assertive?” Standing tall and dressed in black, Shannon Snair commanded attention in a classroom full of 11- and 12-year olds.

It was just past noon at Scio Middle School in rural Willamette Valley, and the sixth graders who had noisily settled into seats moments ago were now listening intently to Snair’s words.

“It’s when you act in a really strong, confident way, letting people know what you need, and why you need something,” Snair said. “And I will tell you, being assertive is not always easy.”

Snair, a county behavioral health worker, spoke with confidence and exuded charisma as she led a lively conversation about situations in which kids may need to stand up for themselves.

Fewer than 1,000 people live in Scio, a farming community, and Snair was visiting its school to teach the final course of the year in LifeSkills Training. It’s one of the most studied and highly regarded substance use prevention curricula available.

Clearinghouse certified studies have shown that LifeSkills can lead to reductions in the use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis years later among students who’ve completed the program.

Spread over three years, it consists of 30 one-hour sessions that weave together demonstrations, practice and student feedback.

Snair, a mother of two, likes that LifeSkills goes beyond teaching how drugs and alcohol will affect kids’ bodies.

“It also teaches kids general life skills,” she said. “We talk about decision making, we talk about self-esteem, we talk about good communication and social skills. We talk about stress, positive ways to cope with stress.”

Scio School District is in the minority. In Oregon, 3% of public school districts use curricula considered by expert clearinghouses to have valid evidence that they specifically reduce substance use.

As part of a larger prevention strategy, Linn County officials chose LifeSkills Training for schools 25 years ago because it was “the most studied program out there,” said Danette Killinger, who coordinates prevention for the county. Sending health workers into classrooms to teach it saves money and ensures the curriculum is being taught as it was designed, she added.

State’s fentanyl awareness curricula effort limited, experts say

Substance use prevention programs with well-documented effectiveness in middle and high schools, like LifeSkills Training, combine lessons in social and emotional skills with drug and alcohol education.

Elementary school programs with strong evidence, such as the Positive Action program used in Vernonia, focus mainly on self-regulation and social-emotional skills.

There’s a big difference between these programs and the goals of a law passed last year, Senate Bill 238, which took cues from Beaverton School District’s recently developed “Fake and Fatal” curriculum.

The law requires the state to develop classroom units that teach the dangers of synthetic opioids and counterfeit, fentanyl-laced pills, as well as Good Samaritan laws, which protect people from being charged with drug possession if they call first responders to aid in an overdose. While it will give students potentially life-saving information, experts say the law falls well short of what’s needed to help them to avoid or delay substance use altogether.

Biglan, who sits on the state’s Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission’s prevention subcommittee, said the initiative is a good idea given the “urgency,” but testing its specific design will be key.

“It is unlikely that any curriculum that focuses on ‘knowledge’ of drugs will have much impact,” said Van Ryzin, who also works as a research scientist at the Oregon Research Institute. In reference to the failed, fear-based attempts at drug prevention, such as the “This is your Brain on Drugs” ad campaign of the 1980s and '90s, he added, “This approach has never been successful, all the way back to those fried egg commercials.”

Teens say schools should step it up

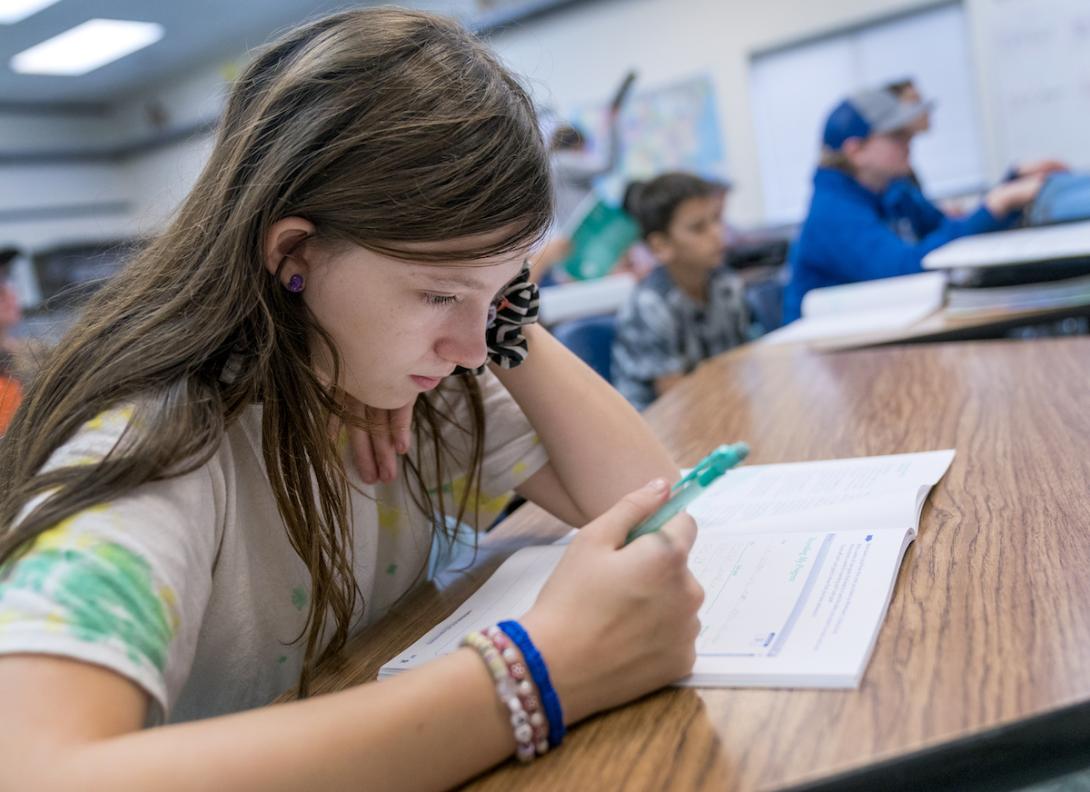

Teenagers at West Linn High School described feeling unprepared when they were confronted with widespread vaping, drinking and cannabis smoking as first-year high school students.

“I’ve lived in West Linn since the first grade, and I don’t recall learning anything about prevention,” said Jonathan Garcia, 17.

“I remember it was like a slap to the face really, when I went to high school and, like, saw everything,” said Claire Peate, 16.

The bottom line is simple, said South Eugene High School sophomore Chazz Keith: “Kids aren’t as dumb as everybody thinks.”

Like other teenagers interviewed, Keith and several of his classmates at South Eugene said they know that they aren’t getting enough quality, up-to-date, straightforward information about drugs and addiction in their classrooms. Schools should do more to educate kids about why people turn to drugs in the first place rather than focusing on scare tactics, they say.

Prevention “just needs to be like, the root of the problem,” said sophomore Bella Kottwitz. “And I feel like in middle school, a lot of it is just teaching like from a textbook.”

And, the teens said, adults don’t get it. Everything has changed, including the substances themselves.

Cannabis has evolved, bred to higher potency and with potential side effects their parents never dreamed of. The meth is different, too, and synthetic drugs bring a whole new array of dangers. Tobacco? It now comes packaged in an array of bright colors and sweet flavors — and vaping is easier for kids to conceal than the tell-tale smell of cigarette smoke.

“The drugs that they grew up with was, like, cigarettes and pot and alcohol,” said Aiden Sauer, 15. “There are a lot worse drugs out right now.”

“And they’re legal,” said Garcia.

“Yeah, and they’re legal now,” Sauer said. “And everyone is just going on about how bad they are. And they are bad, but they’re not giving us any tips or, like, a lifeline to reach out to.”

What classroom prevention looks like

In one survey response, West-Linn-Wilsonville School District officials indicated they employ a prevention strategy delivered through health class, guest speakers, student-led awareness campaigns and supplemental lessons developed by teachers.

But in an interview, Autumn Schmidlin, 15, said she was underwhelmed in a West Linn High School health class where each student had to pick a drug to research and then present to the class.

“A lot of people were joking about it, and they didn’t take it seriously,” she said. “Including me, too, I never really took it fully seriously.” Tasked with presenting on a hallucinogen, she recalled her approach as “I’ll make a colorful presentation, because that’s what you see.”

The Eugene 4J School District’s prevention strategy for middle schoolers consists of health class “plus supplemental lessons,” according to its survey response. The district, however, was out of state compliance for substance use education for several years.

South Eugene High School students told The Lund Report they remembered the lessons as repetitive.

“Every year, you got taught about the same drugs,” said Keith, a sophomore. “It was the same information over and over again, in my experience.”

It’s not surprising health curricula leave impressions like these.

“The point of that health book is to generally teach health,” said Pamela Buckley, a prevention scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder. “It’s not to prevent substance use.”

Additional school district survey results for this project painted a picture of inconsistency and missed opportunities resulting from little state guidance and support:

- Numerous districts, such as Gresham-Barlow, McMinnville and Oregon City, pointed to their health education curriculum as their primary or sole component of substance use prevention.

- Some districts appeared to lump all their “prevention” efforts in the same bucket. Asked about their strategies to reduce substance use, 17 districts listed a suicide prevention program, while others pointed to sex-education programs.

- Of the 119 districts who provided survey results, only 24 noted using programs certified by clearinghouses as evidence-backed at the middle school level — and just 12 districts use these evidence-backed programs in high school.

- Asked to include whether they made certified alcohol and drug counselors available as part of their prevention strategy, 12% indicated that they did.

In addition, 23 districts noted they hold assemblies as part of their substance use strategies, many others noted classroom presentations from local police, government workers or local behavioral health providers. In some cases, isolated events are a district’s only supplement to health class.

But one-time events don’t work — especially if that’s all a school is doing, explained Rick Collins, a prevention specialist at the U.S. Alcohol Policy Alliance, during an online forum on what works in prevention this past May. Collins said that if these approaches are in use, they need to be layered in with “what we know to be some effective prevention strategies.”

Three districts, including Portland Public Schools, use a curriculum developed by the New York-based pro-decriminalization advocacy group, Drug Policy Alliance, which funded the Measure 110 campaign. The curriculum teaches the effects of drugs on the body, as well as advice for safer drug use, such as “start low and go slow” when trying a new drug for the first time. No clearinghouse consulted for this project has yet reviewed it. The Alliance has funded a study to measure the program’s success in promoting “harm reduction knowledge and behaviors,” including changes in students’ level of “drug policy advocacy” after being taught with the curriculum.

“There’s no consistency,” said Pam Pearce, a prominent prevention educator and co-founder of Oregon’s first high school for teens in recovery from addiction. Having herself researched what Oregon schools teach for prevention she said, “The truth is, when you look at what they teach and when they teach, it’s a free for all.”

Not captured in the district survey are individual classrooms where teachers use evidence-backed practices — like Lazar, the Eugene teacher, who uses cooperative learning to teach students. It’s a group learning model that a clearinghouse recently endorsed after a large-scale study — conducted in Oregon — suggested it can lower rates of alcohol use, as well as risk factors that contribute to substance use.

Experts say a 2021 law requiring social-emotional learning be taught in all districts, House Bill 2166, could serve as an excellent foundation for reducing the risk factors that lead to substance use. These programs are aimed at helping kids learn how to manage emotions, feel empathy and make good decisions. Experts say it’s also among the best approaches to early-learning substance use prevention.

But staff members at Forest Grove School District, which embedded a social-emotional learning program in its elementary schools eight years ago, said it takes teacher buy-in and hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to pay for the ongoing coaching and training needed to do it right.

Because of a lack of additional funding and scientific guidelines, experts say the new law’s rollout looks to be flawed from the start.

“The intention is admirable, but the implementation is miles short of where it has to be, and because there is no measurement or accountability, nobody will ever understand just how ineffective it is,” said Mark Van Ryzin, a research scientist with the Oregon Research Institute. He said because districts are free to select programs that aren’t evidence-backed, “millions” could be wasted.

Biglan agreed, adding, “we are doubtful that schools have the capacity and resources to translate the (state) guidance into effective practice.”

All told, this investigation showed that districts around Oregon, lacking funding, support and guidance from the state, are, for the most part, employing untested combinations of programs with scant evidence to back them or, at worst, doing little more than try to meet the minimum standard for health education. And when it comes to implementing meaningful prevention programs that experts say can work, Oregon’s districts fall far short.

Biglan, the senior scientist at Oregon Research Institute, said the gap between “what we know” about prevention in Oregon “and what we’re doing” is vast.

Annaliese Dolph, a former aide to Gov. Kotek, now directs the state Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission. Under Oregon law, the commission works with the Oregon Department of Education to set its youth substance use prevention standards. Told of the project’s findings in an interview, she called the findings “important” but attributed them to Oregon’s tradition as a “local control” state.

“The fact is that districts have a lot of control about what happens in the class,” she said. She likened the situation to past controversy over districts teaching discredited reading curricula and said that given the dismal state of prevention across Oregon, state leaders’ task now is to determine the “next best step.”

State Rep. Lisa Reynolds, a pediatrician and Democrat who represents northeastern Washington County, was more optimistic about the state’s short-term ability to improve the situation in classrooms. She has been pushing for a conversation about youth prevention and treatment in the upcoming legislative session.

Told of the project’s findings, Reynolds said that she thinks things could be improved, despite lack of funding and the longstanding tradition of local influence over school programming.

“It feels like something that doesn’t have to be some huge complicated thing,” she said. “We don’t need to be reinventing wheels … If there’s evidence about what type of curriculum works, then we should do what we can to have schools adopt the programming.”

She said the weaknesses in classroom prevention exposed in this project’s findings “has to be part of the focus” for the Oregon Legislature in its long session slated for 2025, if not sooner.

“It continues to frustrate me as a pediatrician that we as a state, as a society, as a health care system, we’re doing that whole thing of catching the people after they fall off the cliff,” she said. “Wouldn’t it be much better if we put a fence at the top of the cliff? And part of that is education.”

This is an amazing series, and I hope it gets wider circulation. Part of it made to the Daily Astorian, so maybe it will catch on with news media?

There is an unfortunate notion among many Oregonians that anything "science based" is by definition "anti-Christian" and therefore "anti-American". I hope that this information can be translated into language that is not offensive to the communities of faith