COVID-19 cases surged in Oregon last week with highly infectious strains of the virus on the march as it became increasingly clear that some Oregonians, especially in rural areas, are reluctant to get vaccinated.

Oregon providers reported nearly 6,000 new cases for the week that ended on Sunday, a 21% increase from the prior week, the Oregon Health Authority said. That marked the fifth successive week of the current surge, agency officials said Wednesday. The rise led to increased hospitalizations, as well: The number of COVID-19 patients nearly doubled, from about 170 to about 330 patients statewide.

Nearly 2,500 Oregonians have died of COVID-19 since the pandemic started.

As predicted, a highly infectious variant from Britain is on the move in Oregon, overtaking the original coronavirus strain that the vaccines were designed to defeat.

The variant -- B.1.1.7 -- was first identified in Britain in September 2020. It quickly became the dominant strain there and has since spread around the world. It was first detected in Oregon in March, according to the Oregon Health Authority. It is now on its way to becoming the dominant strain in Oregon, Brett Tyler, director of Oregon State University’s Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing, said during an online forum on Tuesday.

Earlier this year, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned that the United States was in a race to get as many people vaccinated as possible to try to stall the variant’s spread. The agency said that by March, B.1.1.7 would dominate in the United States.

Two studies indicate that it is deadlier than the original strain. One found that it was 35% deadlier and the other about 65%

Studies have shown that B.1.1.7 can spread 50% faster, giving it an edge over the original coronavirus strain and two variants that were originally identified in California, Tyler said. They’ve been detected hundreds of times in Oregon but are only about 20% more transmissible than the original coronavirus strain in Oregon.

Another variant that officials are watching is from South Africa - B.1.351. So far it appears to account for fewer cases in Oregon than the British strain, but it, too, is 50% more transmissible than the original version, studies show.

Variants are not unexpected. Viruses mutate, and the mutated viruses can pass from person to person. As a consequence, because the mutant virus strains replicate faster, they eventually take over, which is what we are seeing in Oregon.

The British and South African variants have mutations on the spike protein -- which protrudes from the surface of the virus -- that allows them to more easily attach to a cell, slip inside and replicate. Those mutations also help the variants fight antibodies that are created by the vaccines to fight the virus.

In a draft of a study published earlier this month, researchers at Oregon Health & Science University reported that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was two to three times less effective against the British variant and nine times less effective against the South African strain.

But that doesn’t mean the vaccines are ineffective, said Fikadu Tafesse, assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at OHSU and lead author of the study. He said the study indicates that the vaccines can prevent severe illness and deaths -- but not necessarily infection.

“This shows how important it is to get vaccinated to curb transmission of the virus,” he said.

COVID-19 In Oregon

Throughout much of the pandemic, cases in Oregon have been relatively low. But the latest surge has slammed the state. According to a New York Times tracker, cases in Oregon have soared nearly 30% in the past two weeks, making it the state with the fastest growth during that time. Alabama is next -- with a two week growth rate of more than 20% -- followed by Washington state at just over 20%.

In the United States as a whole, cases have dropped more than 25%.

The tracker also indicates that the rise of hospitalizations in Oregon over the past two weeks marked a nationwide high. Colorado is next, followed by Washington state, with a rise of just over 30% in hospitalizations in the past 14 days.

But in terms of hospitalizations per capita, Oregon ranks 34th nationwide, according to the New York Times.

Cases appear to be surging in rural Oregon, which has some of the lowest vaccination rates.

Grant County, for example, has the state’s highest per-capita rate, according to the state data for last week: just over 700 cases per 100,000 people or more than five times the statewide average. It’s followed by Klamath and Crook counties.

The three Portland-area counties, in comparison, have per capita rates that are all below the state average of about 121 per 100,000 people.

Though cases are spread among all age groups, the share of younger people who’ve become infected is growing. In March, the Lund Report revealed this trend, with an analysis showing that hospitalizations for COVID-19 in Oregon and across the country were skewing to younger people.

On Thursday, Gov. Kate Brown urged Oregonians to get vaccinated in a statement that announced she had extended the state of emergency for COVID-19 for another 60 days. This is the seventh time Brown has extended the order, which gives the state more flexibility in its funding and authority to impose restrictions during the pandemic. The extension comes as 15 of Oregon’s 36 counties will face tougher restrictions on Friday by returning to the extreme risk status. That category bans indoor restaurant dining and capacity in venues like retail stores, gyms and indoor entertainment sites are limited to slow the spread of the virus.

But Brown pledged to reopen the economy within two months.

“I intend to fully reopen our economy by the end of June, and the day is approaching when my emergency orders can eventually be lifted,” Brown said.”How quickly we get there is up to each and every one of us doing our part. Over 1.7 million Oregonians have received at least one dose of vaccine, and over 1.2 million are fully vaccinated against this deadly disease.”

However, Brown said she’s concerned about younger Oregonians catching COVID-19, calling vaccinations the “quickest path” to ending the restrictions.

“Younger, unvaccinated Oregonians are now showing up in our hospitals with severe cases of COVID-19,” Brown said. “Right now, more than ever, as we see the path over the peak of the spring surge and down the other side, we need Oregonians to step up and take on the personal responsibility to get vaccinated.”

The state’s latest data show that residents between 20 and 29 accounted for more than 20% of new cases of COVID-19 during the past week, with those 30 to 39 not far behind. They compare with people aged 60 to 69 accounting for less than 10% of cases with people between 70 and 79 making up only 5% of cases.

Though hospitalizations are on the rise, with physicians seeing an increasing number of younger people who are infected, COVID-19 patients only account for a fraction of the overall capacity.

According to state data, these patients account for about about 10% of intensive care beds that are being used and less than 8% of all hospital beds.

Officials Slow To Track Variants

The surge shows the need for scientists to track infectious variants, something the United States has been slow to do. It requires analyzing the DNA of viral samples to look for mutations.

Dr. Dean Sidelinger, the Oregon state epidemiologist, told lawmakers Wednesday that Oregon has sequenced more than 5,000 samples since the pandemic started. He said that that was the fifth highest number in the U.S. -- but it only represents about 3% of the cases to date.

Neighboring Washington state has sequenced more -- about 14,600 samples so far or about 4% of its cases, according to state data.

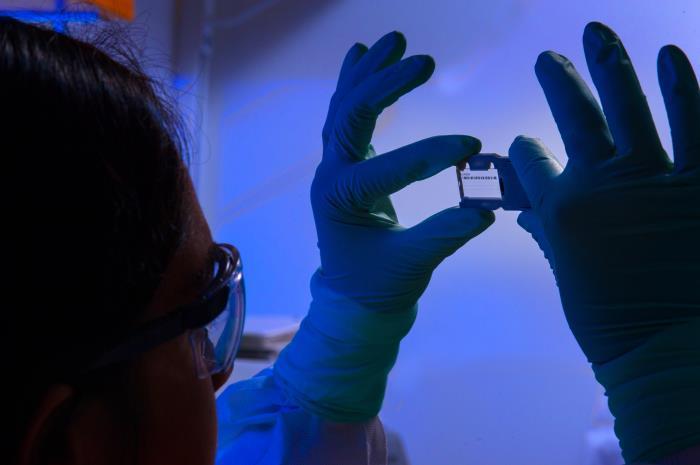

To identify variants, laboratories test for the virus and look for indicators that signal a mutation in the spike protein. Those samples then undergo DNA testing.

Though Oregon has been hit with thousands of cases a week, labs are only conducting genomic sequencing on hundreds of samples. The tests are being done at OHSU, OSU, the state public health lab and the University of Oregon. OHSU is processing the biggest volume -- about 300 samples a week, according to Ben Bimber, one of the scientists involved in the testing. That compares with 40 to 80 at OSU, Tyler said.

The health authority promised to step up sampling -- and it did bring the state lab onboard after tests were well underway at OHSU and Oregon State. Still, the state is not testing to its full capacity of 150 samples a week.

An authority spokesman said the lab ran just over 60 tests last week and nearly 100 the week before, with many of those tests repeats.

“The lab hopes to increase this number in the near future as it completes the validation for additional instruments,” Rudy Owens, an authority spokesman, said in an email.

South African Variant Emerges

Oregon State reported this week that its scientists had found a highly infectious variant from South Africa -- B.1.351 -- in wastewater samples in Albany and Corvallis. The Corvallis samples were collected April 4 near off-campus housing north of the campus, and the Albany samples were taken on March 26 and March 31.

The discovery was part of the university's wastewater project which is trying to track the spread of the coronavirus around the state. The university collects samples in 40 cities a week. When the coronavirus turns up, samples undergo genomic sequencing.

“We are sequencing all positives from wastewater testing,” Tyler said.

The South African variant first emerged in Oregon in March, according to the Oregon Health Authority. To date, only 10 individual cases have been found. The wastewater samples -- which are not from any single individual -- indicate there are many more.

“Following on the heels of the individual cases, the wastewater data supports the fact that the South African strain is here in Oregon, and that it’s likely spreading,” Tyler said.

That’s a concern, scientists say.

Tafesse, the OHSU microbiologist who led the variant lab study, said the South African variant has mutations that give it an edge over the British strain. His study, which he said was the largest of its type to date, looked at how people who’d been vaccinated and those had recovered from COVID-19 responded to the South African and British variants of the virus. The vaccinated group -- 51 people -- were inoculated with the Pfizer vaccine. The recovered group -- just under 44 people -- had been infected with the original strain of the coronavirus.

In lab tests, Tafesse’s team found that the antibodies in the blood of both groups were two to three times less effective at stopping the British strain and nine times less effective at neutralizing the South African strain compared with the original version.

And while the South African strain is less prevalent now, it could become a major worry in two to three months, Tafesse said.

“It’s really important to get vaccinated to be ahead of the transmission,” Tafesse said.

His lab is also looking at the immune response to a Brazilian strain -- P.1 -- along with a variant from New York and two strains from California -- B.1.427 and B.1.429.

His early results show that the vaccine or natural immune response to the Brazilian strain -- which is also in Oregon -- is four to five times less than that for the original coronavirus.

“It is not as bad as the South African strain,” Tafesse said. “But it is more severe than B.1.1.7.”

Similar results were found in a Paris study that was published in March in Nature Medicine.

Research has also shown that the Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines are effective against the British strain but less effective at fighting the South African strain.

But only about one-quarter of the Oregon population has been fully vaccinated.

“This is a dangerous path, and we’ve been down it before,”Dr. Melissa Sutton, medical director for respiratory viral pathogens at the health authority, said in a statement. “We know how these variants spread and we know how to stop them — through consistent masking, physical distancing, avoiding social gatherings and getting vaccinated.”

Vaccine Rollout Varies Among Counties

The vaccine rollout has an uneven level of success across Oregon.

Thirteen counties told the state last week to not send more vaccine, because of low demand, Oregon Health Authority Director Patrick Allen told the Senate Health Care Committee on Wednesday.

“We have very much been diverting those non-needed doses,” Allen said, adding that some of the counties reporting they don’t need vaccines also have low vaccine rates.

Allen called the situation “highly concerning.”

Those counties are primarily in rural areas of the state. The counties are Baker, Douglas, Coos, Grant, Harney, Hood River, Jackson, Lake, Malheur, Umatilla, Union and Wheeler.

Statewide, 40% of Oregonians have started or finished the vaccination regimen, which requires two doses from Pfizer or Moderna. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine requires just one dose.

All the counties that turned down vaccine supplies have lower-than average rates with one exception: Hood River County, with a 49% rate, has the state’s third highest rate.

But most rural counties lag that average and have the lowest rates in the state. Umatilla County has the state’s lowest vaccination rate: 23%. Malheur County has the second-lowest rate of 24%.

Rural health officials are urging residents to get vaccinated and continue to practice social distancing, wear a mask and avoid large gatherings.

In Malheur County, public health officials have noticed a slow and steady decline in demand since mid-March, said Erika Harmon, spokeswoman for the Malheur County Health Department.

“We expected that to happen eventually as vaccine became more plentiful -- there are now more than a dozen COVID-19 vaccine providers in Malheur County,” Harmon said in an email. “But we are concerned about the low vaccination rate, particularly as case counts are rising throughout the state, and we are working to address local needs.”

The county has taken steps in an effort to drive up its vaccination rate. The county has expanded the hours of its walk-in clinics to include evening hours, offered on-site vaccine clinics to major agricultural employers, made field visits to people who are homeless and offered at-home vaccines for the homebound. The health department also worked with the Oregon Health Authority and Federal Emergency Management Agency and ran an eight-day vaccine clinic at the Malheur County fairgrounds earlier this month that reached nearly 300 people.

The county works with community-based organizations and has vaccine materials available in Spanish to reach its Latino population.

“We believe that with persistent efforts to make information and vaccine available, we will see a steady, if slow, rise in the local vaccination rate,” Harmon said.

Malheur County Health Department Director Sarah Poe on Wednesday warned residents in the rural eastern Oregon county about the variants.

“The variants of SARS-CoV-2 are far more transmissible and are leading to more outbreaks and hospitalizations in both Idaho and Oregon,” Poe said in a statement. “I can’t emphasize enough the importance of protecting those who are most vulnerable to save lives and getting vaccinated to prevent outbreaks.”

You can reach Ben Botkin at [email protected] or via Twitter @BenBotkin1.

You can reach Lynne Terry at [email protected] ov via Twitter @LynnePDX.