A British variant of the novel coronavirus that’s highly infectious is making inroads around the state, and a variant from Southern California is also on the move.

Scientists at Oregon State University announced Friday they discovered the British strain, dubbed B.1.1.7, in Corvallis and Bend. Oregon Health & Science University, as The Lund Report revealed Thursday, found the variant in the Portland area, and earlier this month the Oregon Health Authority reported two cases in Portland and Yamhill counties.

The California strain -- which has been roaming in the United States since March -- was discovered in Corvallis, Albany, Forest Grove, Klamath Falls, Lincoln City and Silverton, OSU said Friday.

There’s some evidence that the California strain could thwart a COVID-19 treatment for infected people that relies on antibodies. A mutation of the British variant -- and ones from Brazil and South Africa -- that affects the spike protein on the surface of the virus appears to make it more easily transmissible. There’s also concern about whether the variants are resistant to antibodies produced by existing vaccines.

Though studies are underway, scientists say that getting a vaccination is better than not.

Even if the new variants escape some antibodies, the human immune system produces a rich mix when it’s working well. But the immune response is dampened by illness and age, which is one reason why public health authorities nationwide have put seniors near the top of the vaccination list. They’ve suffered the most illness and death from COVID-19.

Oregon is still vaccinating health care workers and others in the top 1a group -- along with educators, a decision by Gov. Kate Brown that’s been hotly disputed. Seniors are eligible in Oregon starting in February.

“People really need to stay vigilant and maintain protection measures like masks, distancing, washing hands and especially getting vaccinated when they have the opportunity -- even if the vaccine protection is diminished, it’s a lot, lot better than nothing,” Brett Tyler, director of OSU’s Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing, told The Lund Report.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is building a nationwide surveillance system to track worrisome variants as labs focus on spike protein mutations.

The CDC predicts that the British variant, which has emerged in more than two dozen states, will become dominant in the United States in March because of its genetic advantage. The Brazilian and South African strains, which share a similar mutation on the spike protein, are here as well.

On Thursday, South Carolina authorities reported the first two cases of the South African variant, B.1.351, in unrelated people who had not recently traveled out of the United States. The Brazilian version popped up in Minnesota four days ago.

There is some indication -- though hard data are lacking -- that both the South African and Brazilian, which share a key mutation, have some resistance to vaccines.

Both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines -- and the others approved elsewhere or near approval in the U.S. -- are based on introducing the immune system to the spike protein. They now prevent about 95% of illnesses but scientists worry that variants could make them much they less effective.

“We do know there are people that just because of the luck of the draw they don’t get the right set of antibody genes to start off with, or maybe their immune response is debilitated for some reason,” Tyler said. “If they are really unlucky and they get a virus with one of these mutations, they might be more at risk of the virus overcoming their vaccination.”

The Brazilian variant is behind an onslaught of cases in Manaus, the biggest city in the Amazon region. Scientists estimate that three-quarters of its 2.2 million population have already been infected, which in theory would give residents something close to herd immunity. Researchers at the Federal University of Amazonas predicted that Manaus would be the first Brazilian city to defeat COVID-19, according to the Washington Post.

Yet the new strain, which has become dominant, is infecting people who already had COVID-19 caused by a previous strain, and they’re getting sicker and more quickly than they did earlier this year.

Scientists question its resilence to the current vaccines.

Data by AstraZeneca found that its vaccine, which has been approved in Britain and the European Union, was slightly less effective against the British variant and much less effective against the South African strain.

“The effectiveness went down from 90% to 85% (against the British strain) and for the South African variant it seemed to go down to around 50%,” Tyler said.

Similar results were announced this week by Novavax, which is testing its candidate in South Africa. It prevented nearly 90% of illnesses in areas where the British strain circulated but only about 50% of illnesses in an area dominated by the South African variant.

That news prompted long Twitter strings this week, as virologists debated how to interpret the data. One expert, Florian Krammer, a professor of microbiology at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, took a glass-half-full approach: “Let’s not forget, 50% would not be great, but it’s much better than nothing.”

He cautioned his peers to wait for more data.

In the meantime, Pfizer and Moderna -- whose vaccines are being administered in the United States -- have announced that they’re working on booster shots modeled to fight the new variants.

The Southern California variant lacks the mutation that the South African and Brazilian variants have -- E484K. But it could thwart a treatment that’s been used to prevent severe illness, Tyler said. A study published a month ago indicated that monoclonal antibody treatment, which relies on lab-produced antibodies, might not be effective against the Southern California variant and others with similar mutations.

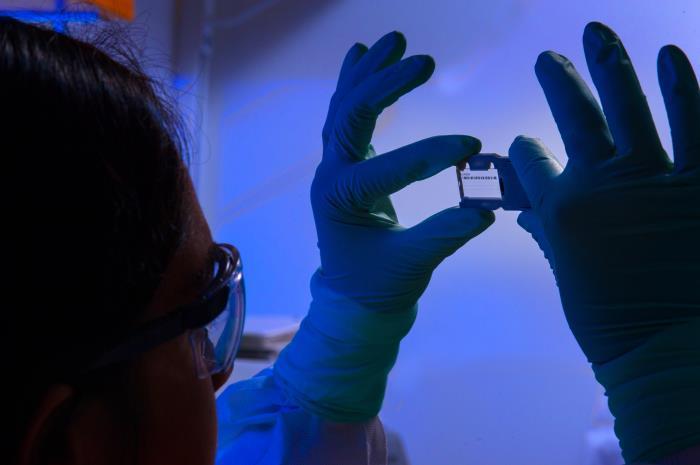

While awaiting more data, scientists say the U.S. needs to step up sequencing tests of the novel coronavirus to better understand the variants and how they spread. The Oregon Health Authority has distributed tests and supplies statewide that will enable labs to conduct more PCR, or polymerase chain reaction, tests that identify a sample of concern. That will help OSU, OHSU and the University of Oregon, which is building its sequencing capacity.

The more scientists know about these variants, the better able they will be to fight them.

You can reach Lynne Terry at [email protected] or on Twitter @LynnePDX.