Past talk of strikes at PeaceHealth never turned into action, said Shawna Ross, a sonographer who belongs to the Oregon Federation of Nurses and Health Professionals.

But on Monday morning, over 1,300 respiratory therapists, radiology technicians, lab workers, maintenance personnel and others at PeaceHealth Southwest and St. John hospitals walked off the job for a five-day strike.

The PeaceHealth walkout is the latest in an increasing trend of health care workers in the region either threatening to strike — or actually doing it. The latest strike is the fourth among health care workers in Oregon or southwest Washington in just five months, affecting six workplaces in all.

The surge began in June, when Oregon saw the first nurses strike in more than 20 years, and workers at three Providence Health and Services workplaces walked off the job. Two different groups of workers at Kaiser Permanente followed.

Health care workers in at least four additional Oregon workplaces have threatened strikes this year, including at Multnomah County, where dentists could potentially stage a work stoppage next month.

By comparison, nurses at three Portland area Providence hospitals and a group of workers at Oregon Health & Science University threatened strikes in 2022, but they all stayed on the job.

In the past, strikes among health care workers were rare because their work stoppages could affect patient care. But health care workers’ increased leverage after the pandemic coupled with their simmering exasperation over chronic short staffing have made strike threats a more common bargaining tool.

The pandemic saw an outpouring of support for health care workers who braved stressful, dangerous and trying conditions. But hospitals, some reporting financial losses, have complained that reimbursement rates have not kept up with cost inflation, including in worker wage demands. And even after COVID-19 subsided, stress and workload concerns remained high as hospitals filled beds and resumed elective procedures as they sought to make up losses.

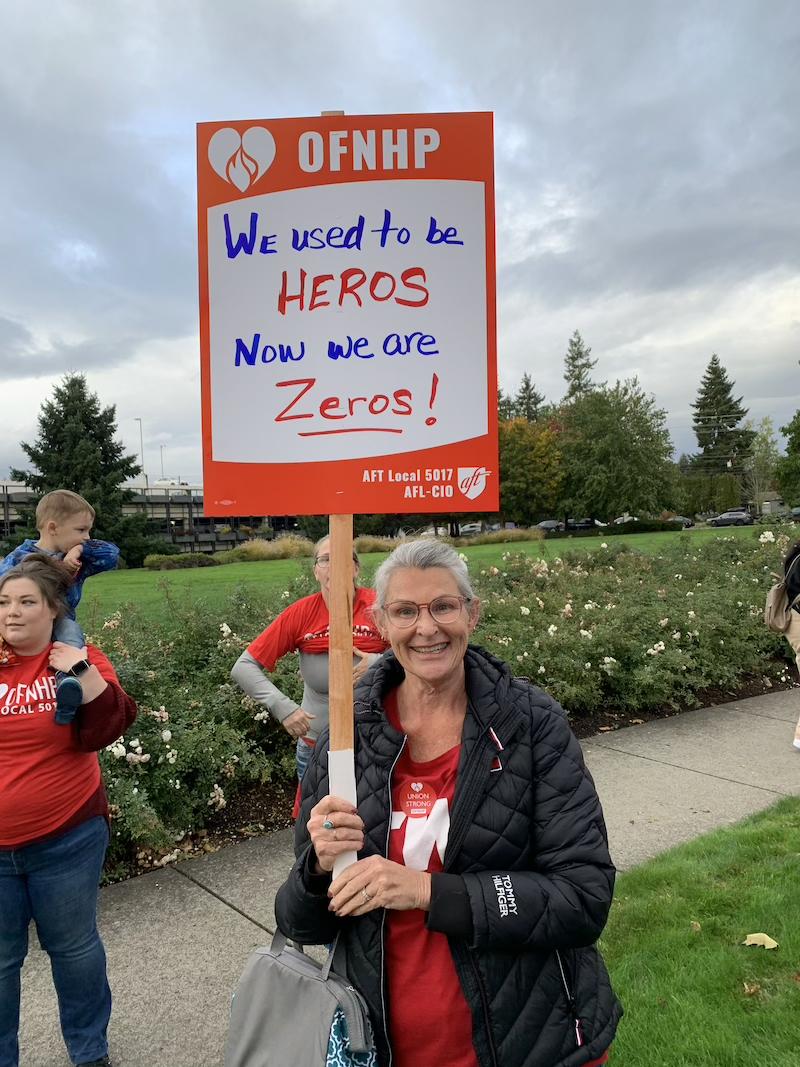

Ross, bargaining chair for her unit, said the contrast between public opinion and the bargaining table is confounding.

“You’ve heard the expression, ‘from heroes to zeros?’” she said. “That is very felt at PeaceHealth Southwest.”

The past five months has shown that the strike authorization votes that some health system officials considered a mere bargaining tactic can no longer be dismissed. Those votes are more frequently turning into multi-day strikes that minimize the impact to patients but also give health systems a taste of what a longer strike would mean for costs and patient care.

No more bluffing

Gordon Lafer, co-director of the University of Oregon’s Labor Education & Research Center, told The Lund Report that unions previously used strike authorizations as a bluff, but not now.

“The level of anger in the health care industry among health care employees, which translates into readiness to strike, is at a level I don’t think I’ve ever seen before,” he said.

Health care salaries in Oregon tend to rate well in U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, but the state’s rank plummets when cost-of-living is factored in.

“The level of anger in the health care industry among health care employees, which translates into readiness to strike, is at a level I don’t think I’ve ever seen before.”

Oregon, like most states, has shed health care workers following the pandemic. In addition to pay, the unions that have gone on strike have cited the underlying issue of inadequate staffing that they argue has hurt patient care and contributed to burnout. Lafer said that understaffing is a key factor driving health care workers toward strikes.

“I think there is a very serious crisis among health care professionals’ ability and willingness to keep working under these conditions,” Lafer said.

Lafer said health care unions face a real test on what health care workers can secure on staffing through bargaining. It will take a structural change in staffing conditions to get back to where unions and management can settle contracts over just wage increases, he added.

Health care workers who’ve gone on strike or threatened to have included highly compensated registered nurses. They’ve also included more modestly paid schedulers, housekeepers, X-ray technicians and others at Kaiser at PeaceHealth.

Following their strike, Kaiser workers declared victory after securing a 21% wage increase over four years that unions said will retain the workforce. The Oregon Nurses Association similarly touted large wage gains after nurses authorized strikes.

PeaceHealth concerns include staffing

The reasons cited for the PeaceHealth strike are familiar: Wages aren’t keeping up with inflation, there’s not enough staff and employees feel undervalued. The union representing PeaceHealth workers has also complained about management’s negotiating practices.

Ross said she leads negotiations for 350 workers who have technical jobs in X-rays, surgery, imaging and others who she said were at higher risk of COVID-19 exposure. She said the lowest paid workers she represents would see a wage increase of less than a dollar in the first year of the contract PeaceHealth management proposed.

Unlike previous negotiations, Ross said that a sticking point has been having enough staff to operate safely. Some departments have half the staff they need and the hospital covers the shortage with staffing agencies while asking permanent staff to pick up more shifts, leading to burnout, she said.

“I’ve been sitting across the friggin’ table with them since June,” Ross said. “Just the stuff that they keep pulling — I’m just tired.”

PeaceHealth responded to the strike with a statement indicating it had hired temporary workers and that patients will continue to receive care. The statement called the hospital system’s previous offers “highly-competitive,” noting that they included roughly 17% pay increases for technical and service workers in the next contract.

“PeaceHealth at all times respects the rights of our caregivers to participate in this and other lawful activities,” reads the statement. “However, we are deeply disappointed that the union has chosen to strike.”

Long-term questions

Nationally, 2023 is on track for a five-year high for strikes as screenwriters, auto workers and others walked off the job, according to The New York Times.

In the strange world of health care economics, however, the potential impact remains to be seen.

Rajiv Sharma, a health care economist at Portland State University, told The Lund Report that it’s not clear what impact assertive labor activity will have on the price of health care.

He said that other sectors of the economy may pass on increased labor costs to consumers.

But health care uses complicated processes to negotiate prices and tends to be more consolidated, he said.

“It is possible that it will lead to higher prices,” he said. “But some of it may be absorbed into other parts and may not result in a one-for-one change.”