Editor's note: The initial version of this article inadvertently failed to disclose that an advocate quoted in this article had agreed to serve as a volunteer on The Lund Report's new Community Advisory Board. The board helps elevate our journalism with feedback from people with lived experience as well as experience in health care, journalism, community work or some combination thereof. I apologize for the omission; please know The Lund Report will strive to ensure it won't happen again. The board's first meeting was Sept. 7; if you are interested in learning more, email me at [email protected].

The Oregon Health Authority is preparing to award a $1.5 million grant to a Portland-based organization that the Oregon Department of Justice has warned is not legally eligible for state funding because of repeated failures to file necessary financial documentation.

As part of the same program, a small organization in Medford with limited relevant experience and a sharp-elbowed approach to local authorities is slated to receive another $1.5 million.

The history and practices of the organizations have raised concerns among proponents of the program, who say the state passed up better-qualified applicants. Kevin Fitts, a longtime behavioral health activist, has been a major advocate for the grant program in question, designed to fund mental health respite centers to help Oregonians in crisis (Fitts is also a volunteer member of The Lund Report’s new Community Advisory Board).

But now, based on the groups the state selected to operate the program, he’s concerned it won’t succeed.

“I don’t want to say, ‘they’re gonna fail,’” Fitts said of the two grantees, but added, “I don’t think OHA has done their due diligence.”

And Fitts is not the only longtime supporter of the program concerned about how the Oregon Health Authority is carrying it out.

Multnomah County Commissioner Sharon Meieran, an emergency room physician and longtime behavioral health advocate, testified in support of the 2021 legislation that approved the new mental health respite program. But now she’s concerned about the nonprofit selected to run a respite center in her county.

“If you don’t have the capacity to respond to the DOJ about the required forms, that does give me pause whether they will be able to provide desperately needed services for a particularly vulnerable population.”

“If you don’t have the capacity to respond to the DOJ about the required forms, that does give me pause whether they will be able to provide desperately needed services for a particularly vulnerable population,” she said.

The mental health respite centers will provide people in crisis a place to stay for two weeks at a time while receiving support from trained “peers,” people with similar behavioral health experiences. It’s a model used in more than a dozen states with what supporters say are promising results.

Health authority spokesman Tim Heider defended the agency’s contracting process in response to questions from The Lund Report. He wrote in an email that the agency followed its standard contracting procedures and that the groups slated for contracts are “registered appropriately to receive funding.”

But the questions around the respite center program’s launch capture the tensions facing health officials system-wide as they prepare to spend $164 million in newly approved funding to shore up the state’s underdeveloped behavioral health infrastructure, on top of the $1 billion lawmakers previously approved. The health authority has pushed to fund grassroots groups and better reach marginalized communities while facing pressure for more accountability — a call Gov. Tina Kotek echoed during her 2022 campaign.

Concerns about health authority contracting and oversight are longstanding, including inside the agency itself. A July 2021 document the agency’s performance auditors prepared observed that at the health authority and its sister agency, the Department of Human Services, “concerns persist about how contracts are conceived, developed, executed, managed, and held to performance expectations.” Auditors added that these concerns were “amplified by recent examples of poor contracting practices.”

And last month, the Oregon Capital Chronicle reported on a recent federal audit finding that the health authority had improperly awarded more than $570,000 in federal funds.

Lawmakers launched program in 2021

In 2021, Oregon lawmakers overwhelmingly approved House Bill 2980 to launch the mental health respite center program. The centers are intended to help fill a gap between outpatient behavioral health treatment and acute care in a long-term residential setting, such as the Oregon State Hospital. The idea is that patients can voluntarily get help during a short-term stay, avoiding what could become a longer, costlier stay in a hospital or long-term residential facility.

Although research has shown peer respite can prevent people’s conditions from worsening, policymakers started small. The Oregon Legislature approved a $6 million program to fund four peer respite centers. The centers will be located in the Portland area, southern Oregon, the Oregon coast and central or eastern Oregon.

After a lengthy delay, state officials in late 2022 issued a notice of its intent to award funds for three of the four centers, naming three nonprofits as the recipients: Black Mental Health Oregon to open a center in the Portland area, Project ABLE to open one on the coast, and Stabbin’ Wagon to open one in southern Oregon.

The health authority did not award funds for an eastern Oregon peer respite center.

Fitts, an advocate who’s received mental health services and spent years lobbying for the program, told The Lund Report he’s concerned about the health authority’s contracting process as well as the capacity of two out of the three recipients.

Project ABLE is well-established, operating for two decades and specializing in peer support for people with mental health challenges. It already employs more than 60 peer support specialists in Salem and McMinnville, records show.

Financial reports not filed

Fitts said he’s worried about the prospects of success in the program for Portland-based Black Mental Health Oregon as well as Stabbin’ Wagon, a recently formed Medford harm reduction group. Both organizations have posted little information online about their finances and organizational structures, despite having received significant funding under Measure 110, Oregon’s drug decriminalization and treatment law.

And, neither have filed financial reports known as 990s with the Oregon Department of Justice.

Records show both state Justice Department attorneys and health authority managers have issued repeated warnings to Black Mental Health Oregon over failures to file paperwork nonprofits need to file to operate in Oregon.

Taunya Golden-David, the executive director of Black Mental Health Oregon, did not respond to multiple emails, phone calls and a Facebook message from The Lund Report seeking comment. Several other people listed as representatives of the group either declined to comment or did not respond to requests to discuss the group’s grant application.

Black Mental Health Oregon’s grant application describes itself as a peer-run organization led by people of color that’s focused on serving “African American/African, Caribbean, and other communities of color,” adding that it has been active since 2016 and currently provides services to 1,500 people weekly, mostly through its free food market.

“Mental stability is knowing that you have food,” Taunya Golden-David, the group’s executive director told KGW in a 2021 story about its food bank.

In 2019 the IRS approved the group’s application to be a nonprofit, meaning it is exempt from federal taxes and donors can deduct contributions from their taxes. Its tax form for that year listed total revenue of $5.

The group’s leaders have not complied with laws requiring it to make similar filings in Oregon, however, meaning it is not legally authorized to raise money in the state, records show.

Since June 2021, Oregon Department of Justice staff have sent eight letters notifying the organization that it was required to register with the department as a nonprofit.

In April 2023, the department warned Black Mental Health Oregon that “this matter will be evaluated for potential legal action” and its board of directors could face penalties if the group didn’t respond.

“I understand that the organization has applied for grants and/or received funding from Oregon Health Authority,” Elizabeth Grant, the head of the department’s Charitable Activities Section, wrote in a June 7 email.

“It is a violation of legal requirements for Oregon charitable organizations to solicit or receive funding without being registered with our office.”

“It is a violation of legal requirements for Oregon charitable organizations to solicit or receive funding without being registered with our office.”

The lack of financial reporting has occurred despite the group receiving significant funding in recent years. The group’s respite center application states that it has a $1.1 million annual budget from private foundation donations, as well as grants and contracts from local and state governments.

Despite the Justice Department’s concerns, the health authority awarded the group two COVID-related grants worth over $250,000 combined. The group also received a $500,000 grant in 2022 under Measure 110, records show. Black Mental Health Oregon filed a report stating it used the money to help families of people with substance use disorders with housing, food and transportation.

In May 2022, a subcommittee of the Oregon Health Authority’s Measure 110 Oversight and Accountability Council rejected an application from Black Mental Health Oregon for more than $3 million to fund transitional housing, harm reduction, outreach and other services for 140 clients a week. Committee members said the amount requested for staffing was excessive and the proposal lacked detail.

O’Nesha Cochran, a subcommittee member, remarked that the salaries Black Mental Health Oregon was asking for were “enormous.”

“Black Mental Health Oregon, yeah, that sounds great,” she said. “But you want $3 million to do what with?”

Oregon Health Authority officials are aware of the warnings that the Department of Justice has issued to the group, and have repeatedly engaged with the nonprofit over its failure to file forms not only with the justice department, but the Oregon Secretary of State as well, records show.

Ebony Clarke, the health authority’s behavioral health director, in a June 7 email urged Golden-David to respond to the inquiries she’d received from the Oregon Department of Justice.

She recommended the group get help to ensure it “complies with all applicable laws,” adding, “We will be providing you with a grant agreement for review and signature soon. Please ensure that you review it carefully to ensure you understand the legal requirements under the grant.”

Grassroots group clashed with agencies

Melissa Jones, director of Stabbin’ Wagon, the group the health authority intends to award a $1.5 million grant to set up a respite center in southern Oregon, did not respond to requests to discuss its plans or respond to concerns raised about its capacity. A person affiliated with the project who identified themselves as “Ira” declined an interview request from The Lund Report.

Jones formed Stabbin’ Wagon in 2021 to reduce the harm from drug use and help stem the rising number of opioid overdoses in Jackson County, according to a KTVL story. Jones became known as the “stabbin’ wagon lady” because of her cart of harm reduction supplies, according to the story.

The Measure 110 Oversight and Accountability Council in 2022 awarded Stabbin’ Wagon a $582,000 grant for harm reduction services, records show. The group’s grant application describes it as a small nonprofit serving Jackson County’s houseless population. Jones stated in her May 2023 grant report that Stabbin’ Wagon served 200 people each month.

In its peer respite grant application, Stabbin’ Wagon states its project will tentatively be named “Trillium Peer Respite” and will consist of a residential home with trained staff.

Its application included letters of support from Rachel Richmond, a clinical assistant professor of nursing at OHSU Ashland Campus. The Massachusetts-based Wildflower Alliance, an established peer organization, also sent a letter of support.

But Fitts said he’s concerned that Stabbin’ Wagon has never operated a community-based day service, let alone a program that will care for people around the clock for two weeks. He also said their confrontational approach to the city and police might be a stumbling block.

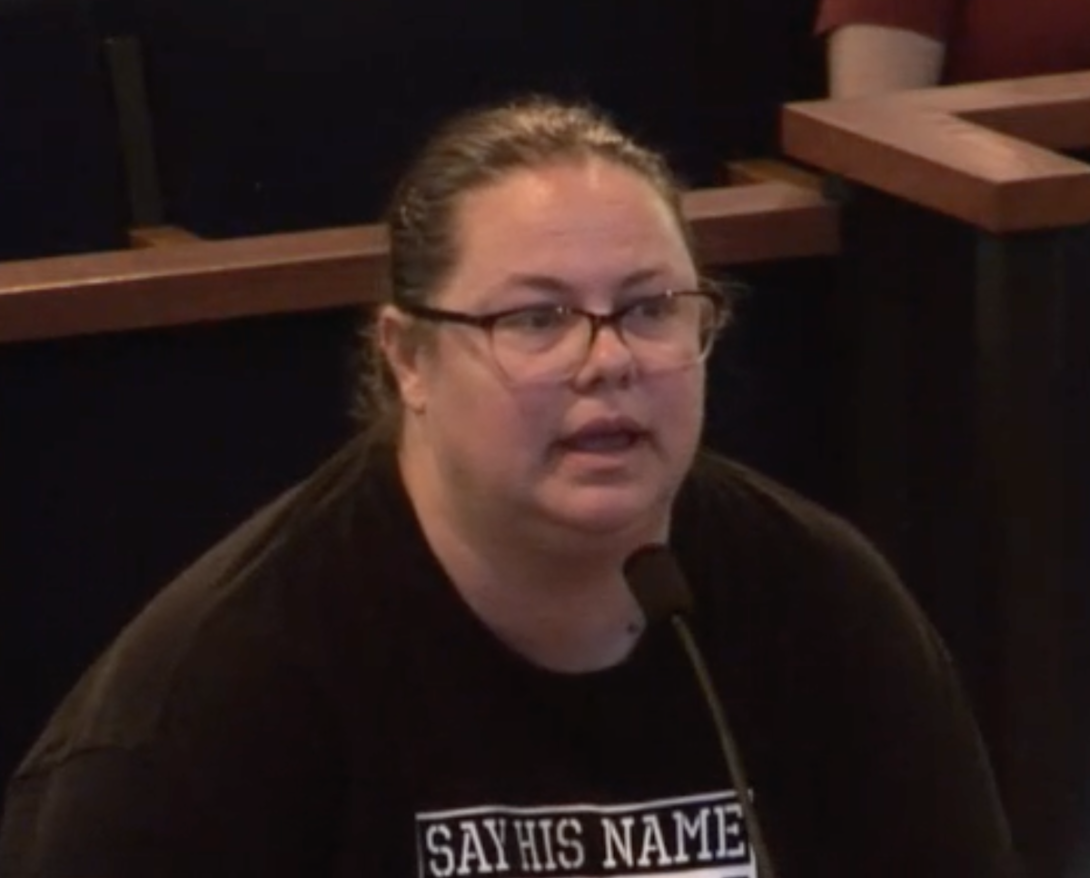

Melissa Jones addresses the Medford City Council on July 1, 2021.

Jones has clashed with Medford city officials over an ordinance that restricted homeless people from using tents for shelter. She angrily confronted Medford City Council in July 2021 over its response to a recent heat wave. She denounced the city’s ongoing homeless encampment sweeps as “inhumane.” The group’s Instagram and other social media accounts are also peppered with derogatory anti-police content.

Find us at #MedfordPride, adjacent to Starbucks! Look for the hideous lime green canopy, next to the @RVPEPPERSHAKERS! pic.twitter.com/TuMisfbhWw

— Stabbin Wagon mobile harm reduction (@stabbinwagonmfr) June 24, 2023

“This is a service project for people in intermediate psychiatric distress,” said Fitts. He added, “They’re going to have to be plugged into the crisis system so they’re going to have to deal with the sheriff and the police.”

Because of the fragile state of guests and the relative newness of peer respite, Fitts said it’s important for organizations providing the service to be integrated into local crisis systems. A guest at a peer respite center might see their condition worsen and need to be transported to more intensive care, he said. He added there is “no doubt” peer respite centers will have to interact with law enforcement.

Records show that in April 2023, Jones tried to register with the Oregon Department of Justice, which gave her an extension while she completed IRS forms.

Peer to peer

Central to the idea is staffing the centers with peers who’ve experienced mental health crises themselves. Dr. Jonathan Betlinski, an associate professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University, told The Lund Report that peer respite has been looked at off and on for the last 200 years. He said that sometimes instead of medications or structured environments, people in crisis just need a break and to be around people like them.

Peter Starkey, executive director of peer-support nonprofit FolkTime, told The Lund Report that people who’ve been hospitalized for behavioral health issues report that spending time with other patients in the smoking area was the most supportive experience. But patients lose that community when they’re discharged, he said.

A peer respite center could benefit someone going through a devastating divorce and worried about their mental state, or someone who is having a resurgence of voices or hallucinations, he said.

“When it comes to mental health, two things that can make it worse are being alone and feeling rejected,” he said. “The biggest thing that peer support and respite does is build community.”

Other groups passed over

Nearly a dozen groups applied for the grants. Fitts and others wonder why more-established organizations were passed over.

The agency’s evaluations of the grant proposals show that Black Mental Health Oregon and Stabbin’ Wagon’s application received high marks for their commitment to the self-determination of people in crisis, inclusiveness, as well as proposed staff training and budgets.

Records show that Bay Area First Step, an established Coos Bay-based nonprofit, was disqualified from the contract because it didn’t meet Oregon’s legal definition of being a peer-run organization where “a majority of individuals who oversee the organization’s operation and who are in positions of control have received mental health services.”

Laura Rose, a longtime mental health advocate who had done consulting work for Bay Area First Step, called it “very surprising” the organization was disqualified.

FolkTime has nearly 40 years of experience facilitating peer-run mental health programs but was not awarded a peer respite grant either.

Given the lack of experience of some of the grant recipients, Fitts said he hopes the health authority provides ample technical support to the groups.

But he also has asked lawmakers and state health authority leaders to reevaluate the process for these grants. Fitts has also filed a complaint with the Oregon Department of Justice regarding how Black Mental Health Oregon solicited state funds while not being legally organized as a nonprofit.

Rose agrees that a group running a peer respite program should have a proven track record. But she said the right team that works well together can deliver a successful program, and she said technical assistance will be key.

“I think each organization has its strengths and weaknesses and those could be factors that come into play for their success,” she said.

Health authority spokesman Heider told The Lund Report in an email that a project coordinator will oversee the peer respite program and will provide “comprehensive technical assistance to peer respites.”

“In addition, the coordinator will facilitate quarterly learning collaboratives for peer respites,” he said. “Plans are to establish an additional advisory council, reflecting the community engagement that has been a hallmark of this project.”

Asked for comment, Starkey, FolkTime’s director, said he’s excited that two groups representing traditionally marginalized groups received the grant.

He said that more grassroots groups could successfully run a peer respite program with the right training and focus. He’s reached out to the health authority with an offer to provide technical assistance to groups that are slated to receive the peer respite grant.

Betlinski, the OHSU professor, is also optimistic. But he said the state officials should set clear expectations for the nonprofits and what success looks like.

“I’m definitely excited by the possibilities. We have a mental health care system in Oregon, but it’s really struggling,” he said. “And I think there’s a lot of people that aren’t able to get (care) in their current system.”

I am deeply concerned about this article, and its implications - both obvious and otherwise.

Peer Respite is an ALTERNATIVE to conventional clinical systems. While I think people understand the idea of it being an alternative in a basic way, a lot nonetheless gets missed.

For example, a MUCH larger problem for peer respite across the nation then less experienced organizations taking on contracts is the rampant co-optation that happens when clinical and other more conventional organizations are awarded these grants. Being an 'alternative' means FAR more than someone with a psychiatric history offering support that otherwise essentially mirrors what's already available. We are not "mini clinicians."

The work needs to be approached in a substantively different manner to truly meet the model standards. Unfortunately, a lot of people who've been using more conventional approaches for a long time simply don't know what they don't know... And for better or worse, it's FAR harder to unlearn than learn.

Awarding grants to groups that have less experience, but are deeply invested in the integrity of the peer respite model is the RIGHT decision. Sure, not every group will be able to carry out the mission, but that's true in any arena, and starting with groups that really 'get it' and are invested in bringing it to full fruition ARE the people for the job. Choosing people based on their ideological understanding and commitment to carrying out the plan rather than focusing on bureaucratic elements is also an act toward undoing some of the oppression and discrimination these groups have historically experienced.

Nothing is going to change if we don't make different choices, even if those different choices are messier at first.

We need to remember that a product of longstanding oppression and discrimination is that people have had less prior access to build up organizations and gain experience. The answer isn't to award the grants to groups that are more conventional and thus already have more resources. Its to award the grants AND provide substantial support to assist these groups in building capacity, and so on.

This is even more true when it comes to Black and Brown led communities and organizations made up of people with psychiatric and other similar histories. They have experienced COMPOUNDED oppressions, and are often given less resources to do more work, and expected to just make it work. If we as a nation are truly invested in undoing/correcting the impact of so much historic oppression, then we need to answer COMPOUNDED oppressions with COMPOUNDED supports to grow and be successful.

Instead, individuals and groups who are already marginalized are FAR more likely to be subjected to scrutiny, criticism, and exposes like this piece. Just imagine if the media took the time to really look at what's going on in some of the clinical organizations in the area. Sure, their paperwork might be in order (though sometimes not even... They just have full departments dedicated to covering that up), but what kinds of abuses are ROUTINELY happening in such organizations across the country? What kinds of poor outcomes are routinely getting excused?

This article represents the sort of treatment that can crush our ability to grow REAL alternatives and serves only to maintain marginalization and what already is.

Anyone who is paying any attention to outcomes in our mental health system (rising suicide rates, increasing mortality gaps with individuals in the psych system dying nearly 30 years earlier than the general population, failures of conventional treatment modalities, etc.) knows that maintaining the current system is NOT the way to go.

-Sera Davidow

Wildflower Alliance