When it comes to drug use, Oregon holds an ugly distinction: Its rate of teenagers killed by overdose is growing faster than in any other state.

But where the public sees a rash of depressing headlines, addiction care providers see the culmination of a story that’s been years in the making. As a result of state officials’ long-standing failure to respond to youth drug addiction, fentanyl — the potent opioid that’s driving the skyrocketing death toll — has dealt Oregon a particularly devastating blow.

A history of warnings

Over the past 15 years, official reports have outlined deficiencies in the youth addiction treatment system.

In 2008, a multi-state-agency report identified “adolescent treatment” as a “top area of need” in an assessment of Oregon’s addiction services. It also noted that limited prevention programs in schools were not consistently applied across districts and needed to start earlier.

When tasked with evaluating Oregon’s treatment system in 2010, the state’s Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission in a report to then-Gov. Ted Kulongoski pointed to “the lack of treatment designed for teens and young adults” as being a “significant gap.”

In 2017, a state committee again tasked with evaluating the system came to the same conclusion. “Resources for detecting or treating adolescents with SUD in Oregon are minimal,” wrote the Oregon Substance Use Disorder Research Committee. “Oregon ranks a dismal 48th in the nation for adolescent treatment access.”

“State spending on substance more than quadrupled since 2005, consuming nearly 17% of the entire state budget in 2017. Less than 1% of those funds, however, were used to prevent, treat, or help people recover from substance misuse,” the Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission wrote in its 2020-2025 strategic plan. Most of that spending was on the “escalating health and social consequences created by the lack of investment in prevention, treatment, and recovery.”

For well over a decade, official report after report has detailed deficiencies in Oregon’s youth addiction treatment and prevention programs.

But people working with youths say the only thing that’s changed is that the problem has gotten worse. And lately, key youth addiction treatment services have dwindled near extinction.

“Professionals in this sector have been trying to wave the flag of warning for 10 to 12 years, with no effect whatsoever,” Heather Jefferis, the executive director at Oregon Council for Behavioral Health, told The Lund Report. “We don’t have a youth system for substance use disorder — we have a handful of providers who do some services. That’s how bad it’s degraded.”

Meanwhile, there’s no statewide system for connecting teens to needed addiction services. And school prevention and education efforts in Oregon have remained minimal for many years, despite repeated calls to ramp them up.

An ex-police officer and a community college geography teacher who’s researched the issue, Sen. Chris Gorsek, D-Troutdale, told The Lund Report that as far as he can tell, in Oregon “there is no current educational work to let kids know about fentanyl.”

And it’s evident. One recent survey of teenagers in central Oregon found 91% knew “little or nothing” about fentanyl, and 95% knew little or nothing about counterfeit pills.

Gorsek introduced Senate Bill 238 to try to address that part of the problem. The Senate Committee on Education is scheduled to hold a public hearing on the bill at 3 p.m. on March 7.

Several other bills have been introduced, and legislative workgroups convened, all aimed at slowing the surge of fentanyl deaths and patching the holes in the state’s addiction care system this legislative session.

But a Lund Report investigation shows how far Oregon has to go in order to address the needs of some of its youngest residents.

High school overdoses and news of fentanyl seizures grab public attention — among Oregonians aged 15 to 24, there were 73 fentanyl-related deaths in 2021 alone, according to federal data.

But lesser known is how the addiction crisis among Oregon teens is intensifying just as youth treatment beds in the state have nearly disappeared.

The state ranks third highest nationally for the rate of substance use disorder among adolescents, according to Mental Health America’s 2023 rankings.

Teen experimentation riskier than it used to be

In the last two years, 18-year-old Portlander Cal Epstein’s story has been well reported. Home for the holidays in December 2020, the first-year college student took a pill he thought was oxycontin — and died from the fentanyl it actually contained.

The little-known part of the story? Cal tried to be safe. His Google history showed that before he purchased the pills, he looked up the appropriate dosage for his weight and how the drug would react with his anxiety medication.

He might be alive today if he had realized the risk he was taking, his parents told The Lund Report.

“He was a person who was adventurous, but he was also cautious,” said his mother, Jennifer Epstein. “He just didn’t have the information that he needed to make the right decision.”

What he likely didn’t know was that fentanyl — a highly addictive synthetic opioid that’s 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine — is often found in pills like the one he was about to take.

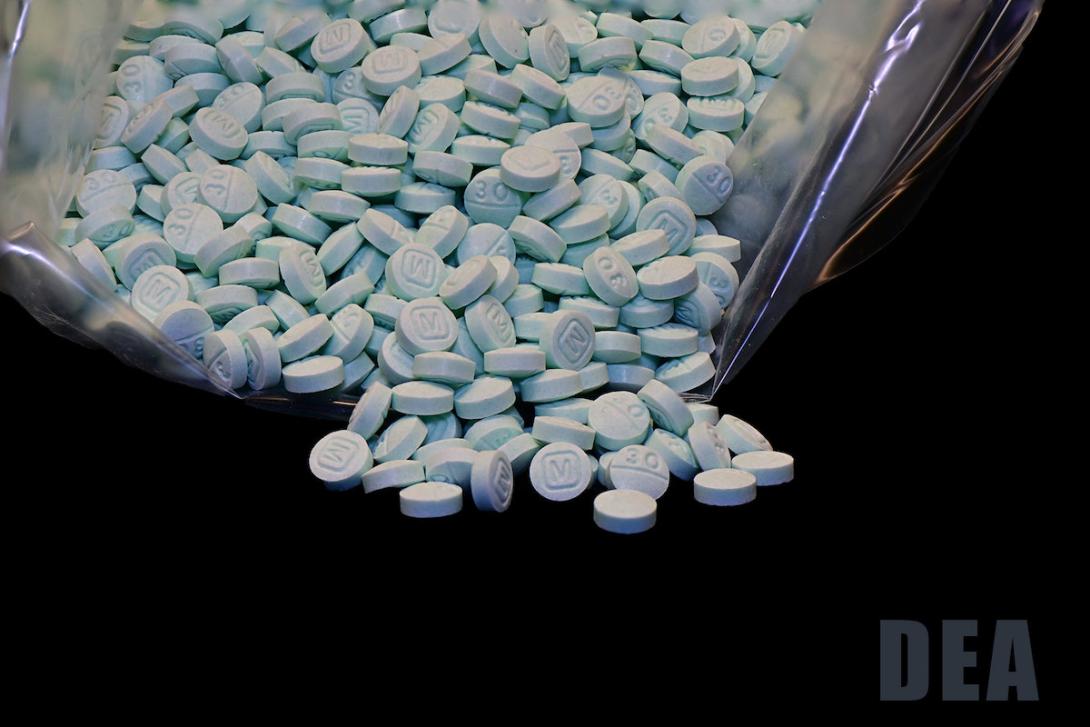

About five years ago, Oregon started seeing a flood of fentanyl-laced counterfeit Xanax, Adderall and oxycodone pills manufactured in clandestine labs outside the United States. Drug makers and dealers had also begun cutting fentanyl into heroin, meth and popular party drugs like cocaine and ecstasy. The goal? To increase potency, save money and increase the products’ addictive qualities.

Since Cal’s death, more people have become aware of fentanyl’s notoriety. But local and national surveys show many teens still don’t know how dangerous or prevalent it is — and the Oregon state departments of health and education have been slow to tell them.

Fentanyl overdoses began to surge in Oregon in 2019, but three years passed before the state offered school districts a way to educate students about the dangers and prevalence of the drug. Even now, neither of the state agencies that put together the fentanyl tool kit — the Oregon Health Authority and Department of Education — are tracking which districts opt to use it.

“There are kids that are dying on their first pill, their second pill — one of their first times experimenting or self-medicating,” Epstein said.

Drug-related deaths among teenagers increased faster in Oregon than anywhere else in the country between 2019 and 2021 — up 666%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A system on life support

Youth addiction care system in Oregon

Residential treatment beds for ages 12-17:

December 2021: 33

December 2022: 31

Adolescents in Oregon in 2020: 299,454

Youth detox facilities: 0

Youth outpatient providers: 12

*Youth inpatient providers: 4

(Many providers have just 1 or 2 FTE dedicated to youth services)

Youth MAT providers as part of an Opioid Treatment Program: 1, Great Circle Recovery

Number of recovery high schools: 1, Harmony Academy

**Est. certified alcohol and drug counselors working with schools: 131

**CADC to secondary school student ratio: 1 to 2,400

Percentage of prevention specialists needed to fill gap: 94%

*excludes specialty programs, such as for sex trafficking victims.

**Based on 2018 percentage (most recent available), with 2022/23 school enrollment numbers.

Sources: Oregon Health Authority, U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Oregon Council for Behavioral Health, Mental Health & Addiction Certification Board of Oregon, OHSU-PSU Oregon Substance Use Disorder Gap Analysis.

Perhaps worse than the lack of prevention and education in Oregon are what resources are available when youths do experience fentanyl and get hooked.

Due to its potent and addictive nature, fentanyl creates havoc in people’s lives at an accelerated rate. With youths, who are often new to opioids, fentanyl addiction can take hold within three to six months, said Dr. Jim Laidler, medical director at Great Circle Recovery, which offers medication assisted treatment to youths. This treatment involves prescribing opioids to combat withdrawal symptoms. Laidler said earlier in his career, it wasn’t typical to see people seeking medication-assisted treatment until they were in their 20s or 30s.

“Now we’re seeing people who are starting in their mid-teens, who are now in trouble, and they can’t stop using it because they become so rapidly addicted,” Laidler said.

Meanwhile, the services available for youth who become addicted have dwindled. Jefferis, of the Oregon Council for Behavioral Health, said the number of residential treatment beds for youths remained relatively stagnant between the 1990s and 2010s, hovering around 120 to 160 beds, even as Oregon’s population grew by about a million. Then the pandemic nearly obliterated the system.

In 2017, there were 144 treatment beds for adolescents struggling with addiction across the state. By 2020, there were 100. Last April, the number dropped to its lowest with 13, according to data kept by the Oregon Health Authority.

Outpatient treatment that meets the gold standard for higher-risk youth — involving multiple appointments each week, after school and on weekends, is able to address mental health issues in addition to substance use, and that involves comprehensive family involvement — is extremely limited in Oregon.

“There are outpatient programs for youth, but if you need more intensive outpatient, you can't find it anywhere in the state.”

“There are outpatient programs for youth, but if you need more intensive outpatient, you can't find it anywhere in the state,” said Dr. Ana Hilde, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at Great Circle Recovery in Portland.

Driving the shrinkage of Oregon’s youth treatment services is the behavioral health workforce shortage that’s plaguing much of health care.

Morrison Family Services in Portland tried to roll out a company-wide outpatient addiction treatment program for youths with co-occurring disorders — the area of greatest need across the state. But despite posting a job opening for more than a year, it couldn’t find a certified drug and alcohol counselor qualified to work as supervisor, and had to drop the idea, said Margaret Scott, the nonprofit’s division director.

Wages in early March hovered around $22 to $26 per hour for 82 certified drug counselor openings listed on a state job page. Providers say that’s not enough to attract the workers they need — but reimbursement rates for addiction care are too low to pay more.

Rimrock Trails Treatment Services has a co-occurring residential treatment program for youths in Prineville that it closed due to a workforce shortage in August 2021. It’s since reopened, but only for boys.

“We are licensed for 24 beds. We’re currently operating at about no more than seven kids” said Rimrock Trail’s CEO Erica Fuller. “We have to turn people away every single day.”

One school district’s program shows promise

Epstein and her husband, Jon Epstein, have dedicated their lives to spreading fentanyl awareness since their son’s death. Epstein began working remotely for a California-based nonprofit called Song for Charlie, through which they’ve done most their advocacy.

Resources for parents and teachers

Song for Charlie’s website offers videos and facts parents can use to educate their kids, as well as toolkits for middle school, high school and college educators and ways to get involved.

The Ad Council’s “The Real Deal on Fentanyl” campaign offers lessons, facts and naloxone instructions.

Beaverton School District’s “Fake & Fatal” lessons and campaign materials are available to any school district that wants to use them.

The Fentanyl & Opioid Response Toolkit for Schools was developed by the Oregon Health Authority and Oregon Department of Education and includes lessons as well as information on how schools can prepare and respond to overdoses.

Watch OHSU’s roundtable discussion on “Youth and fentanyl: What every family needs to know.”

The DEA’s “One Pill Can Kill” page includes information about and images of real and counterfeit pills, as well as information on how parents can check to see if their kids are buying pills online.

The Epsteins first approached Beaverton School District, where their two sons attended school and Jon taught for 10 years. They shared Cal’s story and helped develop a fentanyl education program called “Fake and Fatal.” It included classroom lessons that were taught to all the middle and high school students in the district, a virtual town hall more than 6,500 people viewed live, a social media campaign, getting the opioid overdose-reversing drug Narcan into the classroom, and educating teachers.

Epstein said Beaverton schools lost four students to fatal fentanyl overdoses leading up to the program’s launch in April 2021. Since the program was implemented, however, there haven’t been any the district is aware of, district spokesperson Shellie Bailey-Shah confirmed.

Bailey-Shah said Beaverton School District made all the program’s materials available to any school district. More than 50 districts around the country have contacted the district to talk about the materials, including “a handful” in Oregon, she said.

Whereas lesson plans like Beaverton’s are voluntary, Gorsek’s fentanyl education bill would make it mandatory for Oregon districts to implement. If passed, it would direct state agencies to develop curricula around the dangers of synthetic opioids for public schools by the start of the 2024-2025 school year.

Among other things, his bill would call for teaching students a potentially life-saving fact: that Oregon’s Good Samaritan law protects them from criminal charges if they call 911 because someone is experiencing an overdose.

Tony Biglan chairs the Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission’s prevention subcommittee, which was tasked with building prevention into the state’s mostly-shelved 5-year strategic plan for addiction.

He said there’s a big gap between what Oregon knows about prevention and what it’s implemented so far.

“Oregon is probably one of the strongest states in the country for the research that is done on prevention,” he said.

At least four prevention programs with the proven ability to prevent a range of behavioral problems were developed in Oregon, he added, but aren’t used much in the state — despite being used widely in states like Michigan and countries like Norway and Iceland.

Not just a Portland problem

Oregon’s youth overdose problem is a “statewide tragedy,” as Song for Charlie tweeted last year.

The small eastern Oregon city of Ontario is one of many communities that has seen overdoses increase in recent years.

On the fourth day of school this past fall, an Ontario High School student overdosed on fentanyl.

Ontario Police Officer Casey Walker told The Lund Report he’s responded to numerous overdoses around town. “But this one was a much different feel because it was in the school,” he said. “It actually kind of shook me up a little bit.”

Since 2019, Ontario’s drug problem has “gotten significantly worse” said Mark Keele, a clinical supervisor at Altruistic Recovery, which offers outpatient behavioral health services. He said in Ontario, it’s generational.

And, he’s seeing younger kids coming in for services. “I think the youngest assessment I did was 8 years old,” he said.

Before Bernadino De La Torre became the youth substance use disorder program policy coordinator for the Oregon Health Authority and Department of Human Services, he was a juvenile behavioral health counselor working within schools. When he got to the state level 17 months ago, he got a bird’s-eye view of the system for the first time. “Oh, my God,” he remembers thinking, “Look at look at the rural and the frontier areas, and the need, and the impacts that the opioid epidemic has done to the rural counties as well — and the lack of services there.”

De La Torre began convening a collaborative of youth treatment providers and health agency representatives as a way of figuring out how to “develop a youth system of care in Oregon,” he said.

“We need to come together as community, schools as well, to try to figure out how we can solve some of these problems,” he said. “But then also having legislators really put funding into these areas of prevention, primarily. Prevention has been neglected for a long time.”

When treatment costs too much

For one Portland-area 16-year-old, whose name we’re withholding, what he thought was an oxycodone addiction turned out to be fentanyl.

At age 14, he was using illicit drugs regularly when he overdosed on Xanax. After a two-week wait in the hospital, he got a bed at Madrona’s residential treatment facility in Tigard. He was there 28 days, then discharged. His family couldn’t afford the follow-up outpatient treatment at the facility, he said, and he relapsed about two weeks later.

He said he stayed away from Xanax after that and began smoking “blues” instead, which are made to look just like oxycodone pills. Pills were easy to buy from dealers on Snapchat.

“That’s where people will target kids, because like, social media is just a huge hole,” he said.

“I woke up one day, I remember this day, I woke up and I was like, I need to stop doing this,” he said. Later that same day, in November 2021, in the bathroom at his high school, he said a classmate overdosed when she took a hit off one of his pills.

Following that incident, his mother took him to the hospital for a full toxicology test. She’d been drug testing him at home, but he never tested positive. When she got the results of the hospital test, she asked her son to fess up to what he had been doing.

“And that’s where I was like, OK, well, I’m gonna be honest now. And I was like, ‘I’m smoking oxys.’ And then she’s like, ‘OK, that makes sense, because the only thing in your system is fentanyl.’”

Soon after, his school mandated that he meet weekly for six weeks with a certified drug and alcohol counselor on school grounds. He stopped smoking blues, but drank to soften the withdrawals. Then the counselor referred him to Harmony Academy — which is a recovery high school — where he could attend classes with other kids in recovery and get continued counseling and case management until he graduates.

“That’s when I really was, like, done,” he said. He’s been drug-free ever since.

Changing their environment

Sharon Dursi Martin is the principal at Harmony Academy, located in Lake Oswego.

It operates like a public charter school and currently has 32 students, though the size of the student body always grows as the school year progresses. Some kids travel to the Lake Oswego campus from Forest Grove, Gresham, Colton and even Vancouver, Washington.

Dursi Martin said when students arrive at her campus, it’s often after they’ve faced great difficulty with Oregon’s treatment system. Residential treatment is scarce and hard to get into, Dursi Martin said, and outpatient treatment can be too expensive for many families to afford.

“When I’m interviewing parents, a lot of the time what they’re telling me is that they’re turned down for treatment because their young person is trying to get mental health treatment and they’re told, ‘Well primarily it’s a substance use problem.’ And then they go to try to get substance use treatment, and they’re told that their mental health acuity is too high,” she said.

When youths are denied access to treatment, they often end up in the emergency room.

Harmony Academy tries to shield students from the pressures to use drugs they would likely encounter if they exited treatment to their former high schools.

About 75% of students at the school are completely free of substance use. The other 25%, who are typically testing positive for cannabis or alcohol over the weekend, “They’re talking to the recovery staff about that,” Dursi Martin said. “As long as they’re working towards an abstinence-focused recovery, we’re with them 100%.”

House Bill 2767, introduced this session, seeks to fund more recovery high schools across Oregon. There was no work session or hearing scheduled for the bill as of this writing. If none is scheduled prior to March 17, the bill will die.

Juvenile departments say Measure 110 slowed referrals to treatment

In 2020, Oregon voters decriminalized hard drugs, a move some critics say has had an unintended consequence for youth.

Under Measure 110, people younger than 18 caught with hard drugs can no longer be arrested and diverted into treatment. Meanwhile, another law passed in 2021 eliminated fines and fees charged to youths in the justice system, including those caught with meth, fentanyl or other hard drugs.

For youths, “heroin or cocaine actually have significantly less consequences than marijuana and alcohol right now in our statutes.”

Because of this, “heroin or cocaine actually have significantly less consequences than marijuana and alcohol right now in our statutes,” said Torri Lynn, the director of Linn County’s Juvenile Department. While kids can potentially lose their driver’s license if they have a second court referral for alcohol or cannabis possession, there’s no consequence for harder substances.

Speaking on behalf of the Oregon Juvenile Department Directors Association, Lynn said he and his colleagues take issue with how these new laws took away their ability to send youths caught with drugs to treatment — but did nothing to ensure those youths were getting an intervention elsewhere.

“It’s pretty rare that kids raise their hand and say, ‘I really need to go to treatment,” he said. “The million dollar question: What do we do with kids who have possessed these serious drugs, and how do we make sure that they are getting adequate services?”

Fingers point to schools

While no one interviewed for this story suggested Oregon should recriminalize drug possession for teens, nearly every treatment provider, counselor and advocate suggested schools are key to curbing drug-related deaths and connecting youths to treatment in Oregon.

“Research shows that more than 90% of kids who have a substance use disorder and are in need of treatment are actively attending school,” Fuller, director at Rimrock Trails, said. “That is where they are, and that is where we need to start to identify them as early as possible.”

Possible solutions

Providers, advocates and behavioral health care workers make a number of recommendations for the Legislature, health officials, schools and the care system.

They want the Oregon Legislature to dedicate a portion of behavioral health spending specifically for the expansion of youth programs, such as co-occurring, whole family outpatient and inpatient treatment. They also want further increases in Medicaid reimbursement rates for addiction and co-occurring services.

They want the Legislature to address workforce shortages to support youth-serving treatment and prevention workforce, and robust early intervention and prevention programs in schools.

One provider suggested schools routinely screen students for substance use disorder and mental health.

Others suggested increased collaboration between schools and programs in the community that provide treatment, harm reduction and early intervention.

Schools, advocates say, should be required to inform students about new and dangerous drugs as they surface, create an efficient mechanism for quick response, set up early intervention programs, adopt education programs like Beaverton’s Fake and Fatal, employ more on-site drug counselors, and offer substance use disorder groups and programming.

One counselor suggested colleges should require more addiction education in programs for qualified mental health professionals.

Advocates also want more “recovery” high schools, dedicated to helping youths fight drug addiction.

In August 2021, the Oregon Council for Behavioral Health sent the Oregon Health Authority a list of recommendations for addressing the collapse of the state’s youth and family addiction care system. It recommends modernizing the system and addressing referral and workforce issues. You can read the full letter here.

She suggested in-school behavioral health screenings be as routine as scoliosis and vision screenings. “Then if there are symptoms, there’s a referral, and then it’s tracked and followed.”

Other providers suggested early intervention programs in schools might be effective for students who are using drugs but not yet considering treatment or that they may have a problem.

Oregon’s Department of Education spokesperson Peter Rudy told The Lund Report it’s not realistic to expect schools to play a larger role in screening, intervention and treatment referrals.

“Placing an additional burden on already stretched schools and districts to screen and identify youth, and refer them to what little youth substance use treatment options there are in Oregon is likely not realistic at this time, particularly for school districts already challenged to meet the mental health needs of their students,” he said in an email.

Oregon’s Department of Education is working on some new lesson plans to integrate substance use information into classes for high school grades not currently getting required prevention education. But many prevention and addiction experts say more robust programs that get at decision-making skills and root causes of addiction — that go beyond a chapter in a health book — are needed.

Meanwhile, Rep. Maxine Dexter, D-Portland, has introduced a package of bills aimed at getting the opioid overdose reversing drug naloxone more widely into schools and decriminalizing fentanyl testing strips, among other harm reduction measures.

Rep. Tawna Sanchez, D-Portland, has introduced House Bill 2646, which would require that school staff be trained on the signs and symptoms of behavioral health issues, including substance use disorder, and how to assist students who exhibit symptoms.

Dursi Martin calls education “the tool that works.” She said most kids who are using don’t rise to the level of needing intensive treatment or admission into a recovery high school like the one she oversees. For many of those students, information on how substances impact their minds and bodies, and how they interact with mental health, could go a long way, she said.

“How close the kids in this building are to dying on a regular basis before they get here,” she said, “is unconscionable.”