Faced with the decision of which educational program to choose to combat drug use among students, many school district leaders in Oregon pick several.

This article is part of an investigative series showing that as Oregon kids face a world with increasingly dangerous drugs and unparalleled external pressures, the state’s education establishment has failed to adapt.

To meet the state’s health standards, which require schools to teach kids about the effects of drugs and alcohol, district leaders select a general health curriculum. To address student well-being, considered a critical protective factor against drug use, they select what’s known as a social-emotional curriculum. And to supplement all of that, they sometimes work with local health or law enforcement officials to improve students’ decision-making skills and drive home the possible consequences of becoming addicted to drugs.

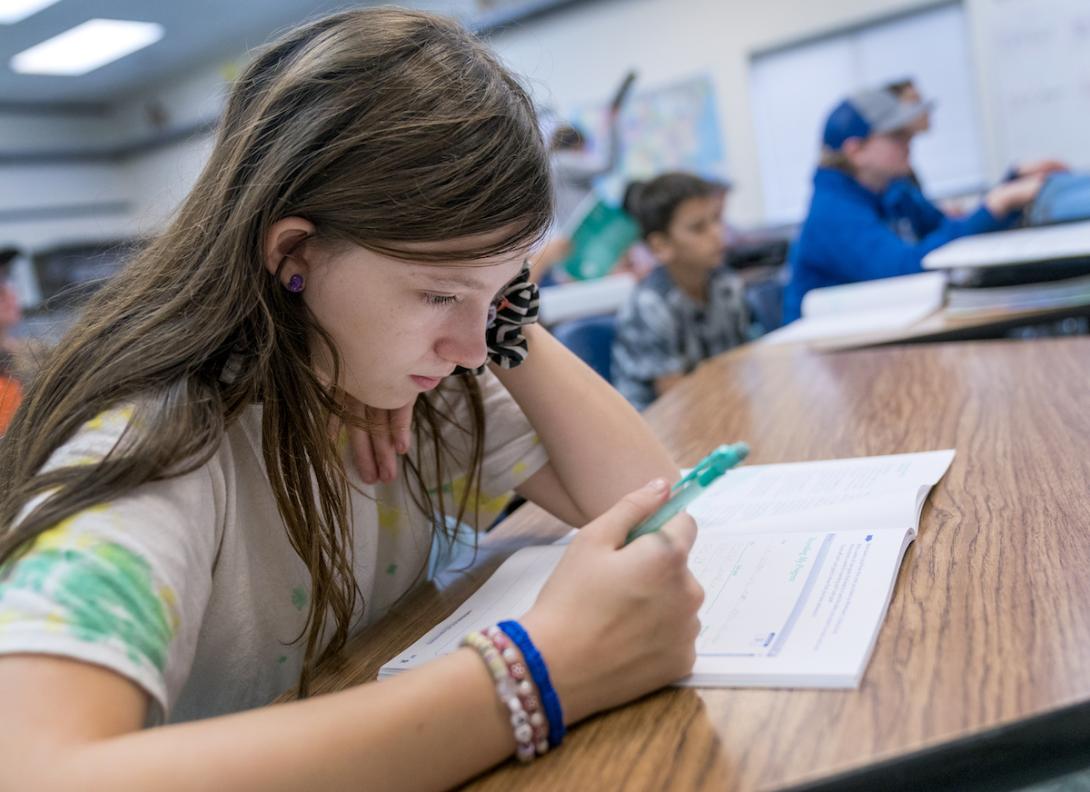

Meanwhile, less than a third of fourth graders in Oregon read or do math at grade level, according to national standardized test scores. By high school, many students have additional concerns – 38% of 11th graders who participated in Oregon’s 2022 Student Health Survey reported feeling depressed in the past year and nearly 70% reported feeling anxiety in the past month. Nearly 15% said they seriously considered suicide in the past year. Students struggling with poverty and housing insecurity need shelter, food and health care.

Public schools are held primarily responsible for addressing all of these issues in the lives of the state’s children, so the goal of finding a program experts have deemed highly likely to reduce substance-use disorder is never the only priority.

In small school districts, it can be a simple question of capacity. There is often just one superintendent and a principal running the state’s rural districts, said Scott Carpenter, the assistant superintendent in La Grande, a nearly 2,000-student district in Eastern Oregon.

Preventing drug use among students is important, Carpenter said, and also “it’s one of hundreds of different hats we wear. It’s a valiant effort. I don’t think anyone is sitting there saying, ‘eh, it’s good enough’ or ‘I don’t care.’”

“I don’t think anyone is sitting there saying, ‘eh, it’s good enough’ or ‘I don’t care.’”

A review of efforts at Oregon’s school districts conducted by The Lund Report and The Catalyst Journalism Project of the University of Oregon and Oregon Public Broadcasting showed that many districts could do much more. Most of Oregon’s school districts use substance use prevention programs that lack evidence of successfully deterring drug use.

School leaders say they are working in a fragmented system and doing their best to meet state requirements, some of which conflict with each other. Many district officials who spoke to Lund for this story pointed out that the programs they were using, like The Great Body Shop health curriculum, had been cleared by the state as being evidence-based. But a national clearinghouse focused on evaluating prevention programs said that evidence of that program’s success is inconclusive when it comes to preventing substance use. And districts get little support to judge substance use prevention programs, like D.A.R.E., that don’t fall under the state’s curriculum review process.

Moreover, district leaders work in a state education system that places scant focus on health as an academic priority, let alone substance use prevention. And time is tight in Oregon classrooms — the state has among the lowest number of required annual instructional minutes in the country at 900 for grades one to eight, equivalent to about 163 days.

“There’s a big focus on reading and math scores and state testing,” Carpenter said. “And so a large portion of our schedules are taken up doing core reading and math or PE minutes or other legislated requirements. Health is not part of that.”

Most districts try a layering approach to substance use prevention

Carpenter is most concerned about students smoking and vaping, since those are the most popular options among his students, according to Oregon Student Health Survey data. In addition to choosing a state approved health curriculum at all levels, La Grande also offers support in the form of a locally created drug prevention program called BEST, seventh grade prevention conferences and individual counseling for high school students. They’ve also made sure school nurses have been trained on how to reverse an opioid overdose with naloxone.

“They are trying to do all these things,” he said of his colleagues, “and, in the totality of that, are we doing the best we can? Yes. Is there always the opportunity for an outside person to look at what we’re doing and say we could do more? Yes.”

Despite increased attention to evaluating such programs, it’s harder to map out an effective school drug use-prevention strategy than one might think.

It’s a challenge to design reliable studies that examine the interaction of multiple programs — a specific health class paired with a specific social-emotional learning curriculum, for example — even though that’s what most schools are offering. And while high-quality research has shown there are a few stand-alone programs that can reduce drug use among children and teens, there are many more that claim to do so with little evidence or only inconclusive evidence that they work.

Take D.A.R.E, a program launched 40 years ago in Los Angeles. First developed by the public schools working with the city’s police department, it became famous for its “just say no,” scare-them-straight approach.

Seven Oregon districts currently use D.A.R.E. Some, like Newberg and Pine Eagle, named it as their primary drug-use prevention strategy in elementary school when surveyed by The Lund Report and the University of Oregon’s Catalyst Journalism Project team. The rest name it as one element in a multifaceted approach.

Most people have heard about the much publicized research finding that D.A.R.E. flat out doesn’t work. But the lessons about 1.5 million American kids are now getting in D.A.R.E. are completely different than those delivered in the 1980s and 90s, said Dennis Osborn, a D.A.R.E. regional director based in California.

Focused on teaching kids to make smart choices, the new D.A.R.E. has incorporated the research-supported concept of teaching kids how to think rather than telling them what to think, Osborn said. Lessons are still delivered by law enforcement officers.

“D.A.R.E. is not a drug-only program anymore,” said Ashley Fraizer, the PhD in charge of curriculum development at D.A.R.E. “We teach some foundational skills that include those underlying mediators that are related to drug outcomes: their confidence, their resistance skills, their beliefs about the consequences of engaging in risk. Those skills are effective for managing your behavior in all situations, including staying out too late, gossiping, being online too long, whatever kind of risk you’re talking about.”

Frazier points to several recent studies suggesting the revised D.A.R.E. is effective. But the evidence produced by a well-designed 2017 study of the new version of D.A.R.E. is inconclusive, according to the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention’s CrimeSolutions database, which evaluates research of drug and crime prevention interventions. And none of the other more recent studies have been evaluated as showing effectiveness by the other national clearinghouses The Lund Report consulted for this project.

Frazier isn’t sure she cares. “I think it’s complicated,” she said when asked why D.A.R.E. wasn’t listed as an evidence based program in any major federal database.

Getting into schools to do research is hard these days, she said. District leaders are protective of students’ time and don’t want to layer on one more assessment. She also thinks old D.A.R.E. just has a bad reputation and no one will give new D.A.R.E. a chance. Fraizer said that she has chosen to focus on keeping the program up-to-date for the kids still getting the lessons rather than on submitting studies to the expert clearinghouses.

She argues educators have to change the way they think about what counts as evidence that something works in schools. “People want to come at me about ‘is this proven to work?’ And I’m like, ‘Not for nothing dude, but does your kid know how to read?’”

New programs may work but are untested

In Hillsboro, a diverse, largely suburban district serving nearly 18,800 students, educators recently chose a program called Character Strong to supplement their health curriculum. It’s a social-emotional curriculum that was born in Seattle Public Schools two decades ago.

After many years as a local initiative, the teachers who started Character Strong formed a company to package and sell an elementary and secondary curriculum that they say improves positive social behavior, improves life skills and increases students’ feelings of connectedness to school, among other outcomes. All of these listed outcomes are known to be protective factors against drug use. But the program is not, strictly speaking, aimed at preventing drug use.

“We look at it from a recipe metaphor,” said Clay Cook, the chief curriculum developer at Character Strong. “We believe what we do is a really quality ingredient. We would never ever say, ‘Hey, Character Strong is your substance-use prevention solution.’”

Educators in Hillsboro and 25 other Oregon districts have decided to offer Character Strong as part of their drug use prevention strategy.

“I think it’s very strong,” said Xylecia Fynn-Aikens, a senior teacher with a PhD in educational leadership who helps oversee the program in Hillsboro schools. “I connect closely with the Character Strong coaches and trainers. I believe the tools are wonderfully useful and very accessible.”

Since Hillsboro’s decision, five other Washington County school districts have adopted the program, assisted by funding from the county’s health department.

These districts made their decisions based on research cited by the company, before the program won approval by any of the top substance use prevention clearinghouses that review evidence of effectiveness. That lack of clearinghouse endorsement is about to change. Character Strong has been accepted into the Evidence for ESSA database, a project of Johns Hopkins University, with a rating of “strong,” according to Cynthia Lake of Johns Hopkins University who was involved in the review. But it’s been a long process to get there and without schools trying the program before it was rated, there could be no studies proving whether or not it worked.

State only reviews general health curricula

For districts, the decision of what materials to offer in schools might not be directly connected to what the research shows. Sometimes, it’s more about what they perceive as working right in front of them and what they understand works best, given their experience educating kids.

And other times, it’s mainly about meeting state requirements. When choosing a general health curriculum to meet state standards, many districts look first to see what the state had vetted.

“We feel strongly we have to adopt off the state approved list,” said Brennan Brockbank, the health and science coordinator for David Douglas School District in Portland.

Among the metrics the state checks: Does the curriculum address eight separate areas of health, including substance use prevention, and does it have research backing up its general effectiveness?

The Great Body Shop is one of just two health curricula to meet the state’s standards for K-5 students in Oregon. Correspondingly, at least 62 districts use it in their classrooms.

But expert clearinghouses on substance use prevention do not rate The Great Body Shop as backed by sound evidence. Blueprints, a research clearinghouse at the University of Colorado that looks at the prevention of problem behaviors, rates the program as having insufficient evidence of effectiveness. Meanwhile, the Department of Education’s clearinghouse hasn’t evaluated it and it doesn’t appear at all in Johns Hopkins’ Evidence for ESSA.

The Great Body Shop did not respond to multiple requests for comment on its curriculum or on the research listed on its website. Summaries of that research on the site claim it reduces violent behavior, among other outcomes. Even that research, which a Blueprints investigator called “weak,” does not claim that learning Great Body Shop lessons protects against drug use.

Substance abuse prevention is “not the most important topic covered in health. By time, sex ed is given more time and weight.”

And even if it did show effectiveness under research conditions, Brockbank from David Douglas said it might not work that way in real life. Elementary school students in his district have just 30 minutes a day in their schedule for “content,” which includes social studies, science and health, among other topics. He said teachers offer health lessons when they can, but often shorten or modify them from the recommended format.

“Teachers say they don’t have time to teach everything in the Great Body Shop,” Brockbank said. “It needs editing. It also needs to be accessible to English Language Learners. Folks consider it a resource, but not a prescription.”

That means students are exposed to some of the content in the curriculum, but not all of it. It also means teachers are not teaching the curriculum as intended. Brockbank also said that substance abuse prevention is “not the most important topic covered in health. By time, sex ed is given more time and weight.”

Sarah Benes, the president of the Society of Health and Physical Educators, said the extremely limited time educators are able to spend teaching health is a national problem.

She thinks that the social and environmental factors that drive drug use play a bigger role in kids’ decisions to use than health education could. That said, she also thinks better and more health education has enormous potential to give kids the tools they need to do a good job navigating difficult choices about exercise, nutrition, sex and drugs, among other topics.

“We don’t give health education enough time to do what it could do,” Benes said. “What, you’re going to give them five 30 minute lessons? What did you think it would do?”

No one would argue for teaching kids math in just five lessons a year, she said. And yet, in Oregon, kids often have to make major life decisions about their health with little more background than that.