Sunday marked exactly a year since the first day of the “heat dome” in Multnomah County, when several days of excruciating temperatures killed dozens of people.

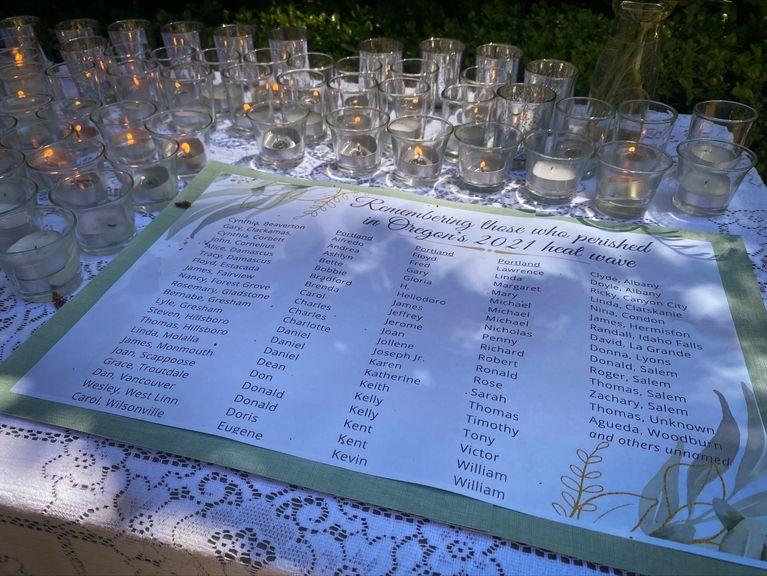

Local politicians and organizations are hosting a series of events called Heat Week to commemorate people who died during the extreme weather, and to make calls to address climate change. The events started Sunday with an outdoor gathering at the Leach Botanical Garden in Southeast Portland on what happened to be the hottest day of the year so far.

As temperatures just about reached 100 degrees, speakers stood beneath the sweltering mid-afternoon sun to recall the most deadly heat event the region has experienced.

“In a typical Portland summer, as you all know, until last year, [heat deaths] were literally unheard of; they were literally zero,” said Multnomah County Health Officer Dr. Jennifer Vines. “And last year, over the course of the heat dome, we ended up with 69.”

There were likely more deaths that are unaccounted for, according to Brendon Haggerty of the Multnomah County Health Department, who supervises a program overseeing the health impacts of climate change. Haggerty helped the county publish a report Sunday that studied deaths related to the 2021 heat wave.

Haggerty told the crowd that death data suggests last year’s heat likely contributed to other deaths.

“In a typical year, there are around 95 deaths from all causes in the last week of June,” Haggerty said. “But last year there were 186, nearly double the average of the previous three years.”

During that week, there were 257 emergency department and urgent care visits for heat illness, according to the report. In a typical year, there are 83.

The county’s report says 69 deaths were directly tied to the heat dome disaster. Some key findings related to the people who died include:

- 56 people were 60 years and older.

- 48 people lived alone.

- 42 people were living in multifamily units like apartments, and 14 lived above the second floor.

- Four people were homeless.

- 10 people had air conditioning, and of those, seven had units that were unplugged or not working properly.

- Six people lived in apartment buildings owned and managed by Home Forward, a local housing authority that houses low-income people.

Also, 42 people died in the county’s identified “heat islands” — neighborhoods that typically sustain the highest temperatures because of several factors, including too much pavement and not enough greenery.

Between June 25 and June 30 last year, the county recorded three consecutive days of 108, 112, and 116 degrees, according to county data. Before that month, the highest temperature on record for Multnomah County was 107 degrees. Those temperatures were also unusual so early in the year, when people’s bodies hadn’t yet acclimated to the summer heat. Then the heat stuck around into the night, providing little relief to people who didn’t have air conditioners at home. The report says this was an “extreme and unprecedented” for the Pacific Northwest, and that it was a “one-in-a-1,000-year” heat event — meaning that, statistically speaking, a heat event like that has a 0.1% chance of happening in any given year.

Heat Week event organizer Vivek Shandas — also a Portland State University professor who studies urban heat — said the chance of similar heat waves in the near future has increased with climate change. He said regions like the Pacific Northwest that are 45 degrees above the Earth’s equator aren’t used to heat like this.

“Communities at this higher latitude are arguably the most underprepared for these kinds of events,” Shandas said. “We saw that really bear down on us last year.”

During Sunday’s event, local politicians and government leaders noted lessons learned from last year, and changes that have been made since then.

“We’ve increased coordination efforts between the city and county to make sure we have a single unified response to severe weather,” Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler said. “We’ve focused response efforts on people with fewest resources.”

Wheeler said the city is prepared to open cooling centers when temperatures remain too high for too long, as well as misting stations at five public parks.

The city and county didn’t open cooling centers over the weekend, even as temperatures peaked well into the 90s, because overnight temperatures dipped into the 60s, which leaders said provides some relief to people who don’t have air conditioning.

CORRECTION on June 29: An earlier version of this story mistated the number of heat-dome related deaths.

This story was originally published by Oregon Public Broadcasting.

It is confusing with this in such recent past, that given last weekends heatwave the cooling centers in Multnomah County were not opened. They told people to go to a library instead. The centers in WA County and Clackamas were opened. Is there a standard criteria the counties go by to determine appropriateness of cooling center opening? Thank you for this article.