This article has been updated to incorporate additional reporting.

A 21-year-old Portlander who makes less than about $29,000 a year would have their health insurance costs erased under a proposed new health plan.

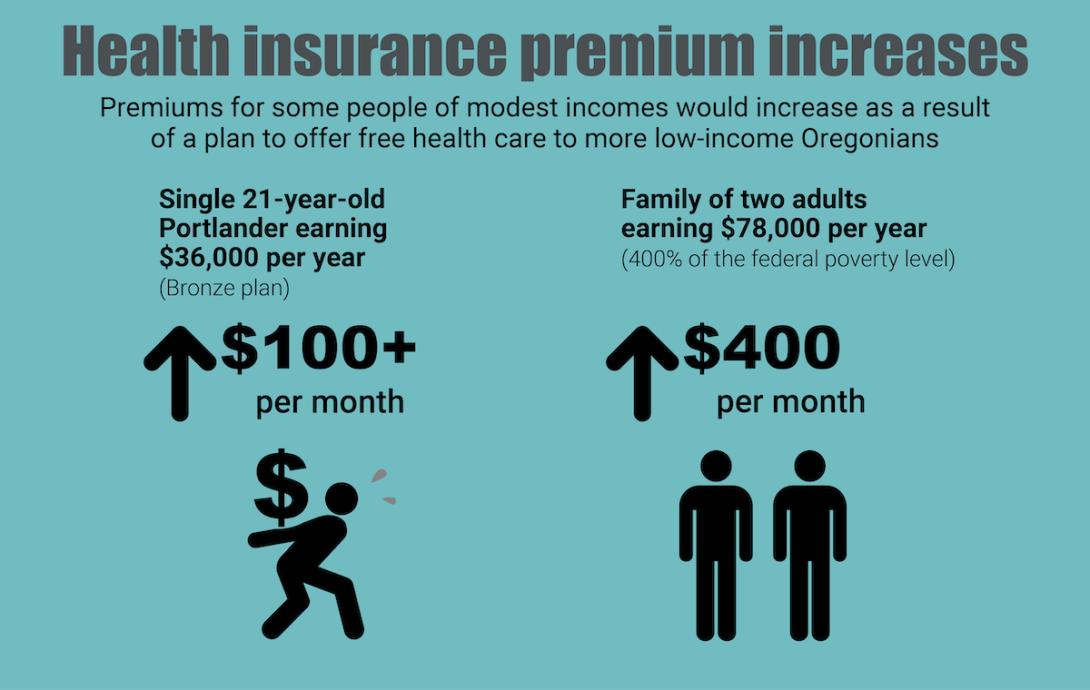

If the same person earned a bit more, however, they could see the cost of premiums for a modest, marketplace health insurance plan jump more than $1,300 annually because of the new state program. That’s the scenario Kaiser Permanente number-crunchers estimated for an average 21-year-old making about $36,000 a year — a full-time hourly wage of less than $17.50 — who would see their premiums for a relatively low-cost bronze-rated plan more than double in Multnomah County. That’s a plan that already has high out-of-pocket expenses.

All told, the proposed Basic Health Program designed by state officials would eliminate health care costs for about 90,000-100,000 lower-income Oregonians. Supporters, including state health officials, lawmakers and a wide array of reform advocates, note the program would stabilize coverage and avoid interruptions of care for lower-income people, who tend to often lose their plans as income fluctuations make them ineligible. And data suggests it would also help reduce racial and ethnic health disparities.

But elements of the program's current details have strayed in significant ways from the aspirations of the task force that birthed it. And while state officials downplay the impacts on people who don’t qualify for the program, they agree with health insurers that —as a result of recent developments — the new program will significantly raise the cost of health premiums for many thousands of Oregonians who are not on government insurance or covered through their employers, but who instead buy their own plans directly from insurers or on the online insurance marketplace.

The program’s disparate impacts have fueled a debate that lawmakers haven’t taken up in the current session. Instead, concerns were aired largely behind the scenes — including in letters submitted during a public comment period ending this Friday, June 9. One insurance executive said state data shows nearly 20,000 Oregonians would pay an additional $900 or more a year due to the premium hikes, and another said the program would do “more harm than good.”

“A family of two adults would make $78,880 annually at 400% (of the federal poverty level),” a Regence BlueCross BlueShield executive wrote in a June 6 letter to the state. “Under this proposal, they could see marketplace premium impacts for their family of $400 a month, or $4,800 a year. Most families could not absorb this level of insurance price increase in light of increasing rent, food prices, gas prices, and other inflationary pressures, and many may become uninsured.”

Two recent developments are raising new questions about the program’s prospects for success. In recent months, plans to curb the premium hikes expected in Oregon went awry when the federal government rejected provisions designed for that purpose that the state’s program task force had proposed. Then, in April, a reputable new study suggested that the assumptions underlying the Oregon program’s aspirations for success may have been overly optimistic.

State officials, however, have continued to press ahead with the program design they intend to submit for federal approval. In the June 6 meeting of the Oregon Health Policy Board, which oversees the Oregon Health Authority, policy analyst Tim Sweeney said the state’s hired actuaries estimate the premium hikes will cause less than 2,000 people to drop their coverage. He said the proposal will help prevent as many as 20,000 low-income Oregonians from dropping their coverage entirely, calling the Basic Health Program “the best way to protect the coverage gains that Oregon has achieved over the last three years.”

State faulted for leaving public in the dark

But the extent to which the public understands the proposal is unclear, and some say the agency is to blame. Finding information about its projected effects on health premiums has been difficult, as it is not included in the public summary that the public is supposed to comment on. The most comprehensive information on the projected premium hikes was not shared publicly until the June 6 meeting Sweeney spoke at — three days before the comment period closes. Even finding out how to submit a public comment on the proposal is challenging, with the information buried in meeting packets.

At a recent public hearing on the plan only a single member of the public spoke. Citing the paltry attendance, the well-connected health official who co-chairs the state’s Medicaid Advisory Committee said the health authority had not done enough to educate the public about the plan and opportunities to weigh in.

“I think it would be advisable to OHA to continue to reconsider public engagement about this process.”

“The only reason I heard about public comment was because I was formally a part of this committee. So it didn’t show up in other community forums I participated in; it didn’t show up in the places where I access health care,” said Adrienne Daniels, co-chair of the agency’s Medicaid Advisory Committee and a top clinical services manager for the Multnomah County Health Department. “I think it would be advisable to OHA to continue to reconsider public engagement about this process.”

The challenge of assessing the proposal in light of how it has evolved now falls to the state’s health policy board — the body the governor appoints to oversee the health authority, which will make the final decision on whether the program goes forward. At its meeting on Tuesday, three members who commented on the staff presentation openly expressed difficulty following it — showing the complexity of the subject matter.

Staff cut the presentation short due to lack of time, and Sweeney told board members he would “skip” explaining to the board an assumption underlying state projections that state actuaries had asked to be shared at the presentation, one that amounts to an important caveat. The significance of the assumption is that the projections shared with board members and the public don’t provide the full, cumulative picture of likely premium hikes in 2026 and 2027.

Program launched with urgency

As the pandemic wreaked havoc on the U.S. economy, the federal government issued a rule blocking states from kicking people off Medicaid, which provides free care for low-income people. The Oregon Health Plan grew from 1.1 million to 1.4 million members as people who normally would cycle off due to increased income instead kept their coverage.

The rule was expected to go away in 2022, sparking estimates that as many as 300,000 Oregonians would be kicked off the state plan. So lawmakers set out to create a new program that would essentially be layered on top of the Oregon Health Plan to accommodate a portion of those who make too much to qualify for Medicaid, the cutoff for which is an income of 138% of the poverty level.

In all, about 55,000 people stood to lose their Medicaid-funded free care for earning too much, despite earning less than 200% the federal poverty level — the standard many consider to be low-income.

To enroll people falling in that income range into free or reduced care, the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act allows states to apply for federal approval to set up a Basic Health Program. So far only Minnesota and New York have done so, in 2015 — though they did so to continue preexisting programs, not set up new ones. Another state, Kentucky, also began developing a program during the pandemic, though it abruptly halted work on the project in November.

Oregon would be the first state to set up such a program from scratch. Its new Basic Health Program would offer free care to people making more than the Medicaid cutoff, all the way up to 200% of poverty level — which is $29,160 for one person or $60,000 annually for a family of four.

Rather than hash out the program's elements themselves, Oregon lawmakers took an unusual approach to save time and try to keep people enrolled. The Legislature passed House Bill 4035 on a near party-line vote just two months into the 2022 session, essentially granting lawmakers' preapproval to a program that hadn’t been designed yet. The bill delegated the work of program design to state health officials working with an appointed task force and consulting with federal officials.

One point of hope for the task force was the financial success of New York, which had set up a Basic Health Program that built up a surplus with the help of federal funding. In Oregon, the thinking went, similar surpluses would be used to eventually raise reimbursement rates for providers above the low Oregon Health Plan rates they would receive early on.

Premium hikes to hit some people with lower, middle incomes

Still, members of the task force had to grapple with a complicated wrinkle: the new program would boost premiums for people who are not on Medicare and buy their own insurance policies, typically through the online health insurance marketplace created by the 2010 federal Affordable Care Act known as Obamacare.

That’s because the new Basic Health Program would not just be open to people coming off Medicaid; it also would absorb a portion of people who currently use the online marketplace. Currently, most of the 168,000 people who buy their own insurance plans and are not on Medicare use the marketplace. About 100,000 of them receive significant subsidies because they earn between 138% and 400% of the poverty level.

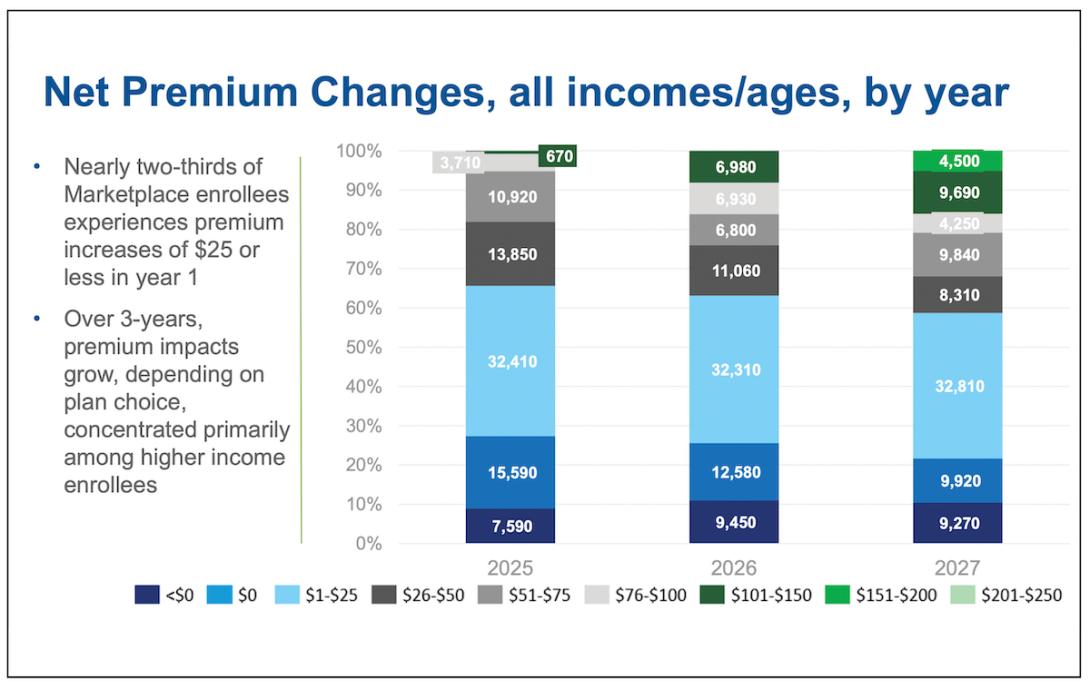

The state’s proposed new plan would require an estimated 36,500 people to join the new program and leave the marketplace over three years. Because of how the marketplace sets subsidies, this change would have the effect of raising premium costs for many of the people who don’t qualify for the new state program and remain on the individual market.

The larger hikes generally would fall more on people making at least 400 percent of the poverty level— but also would significantly affect some people of more modest incomes, like the 21-year-old Multnomah County resident that Kaiser Permanente cited. The biggest premium hikes would affect people who’d purchased gold plans, which are designed for people with the greatest health care needs, or bronze plans, which are typically selected by people trying to keep costs down. The hikes could make some people with those plans reduce or drop coverage, according to the state.

The program would also cut revenue for health insurers and providers. The plan would take a population of about 100,000 people who could buy heavily subsidized coverage from insurers on the marketplace and put them instead into the delivery system set up for the Medicaid-funded Oregon Health Plan. Meanwhile, providers would take an income hit because the new plan’s reimbursement rates would be cut to Medicaid levels, at least initially.

Advocates said the hit to providers’ incomes could cause some to stop providing care to lower-income people, further hurting access that’s already been a problem in many areas. Insurers, meanwhile, say the state’s projections downplay how the new program will disrupt the marketplace and hurt even people of lower incomes.

Anthony Barrueta, the senior vice president of government relations for Kaiser Permanente, in December 2022 submitted a comment to federal health care officials suggesting the state’s assumptions were optimistic, while calling Oregon’s Basic Health Program a bad idea.

“... we have significant concerns that establishing a BHP in Oregon would do more harm than good through its impact on enrollment, premiums, and provider rates.”

“Under the State’s assumption that only a modest number of enrollees will choose to be uninsured, those who remain in the market will be financially burdened or inefficiently covered,” he wrote. “These outcomes conflict with Kaiser Permanente’s view that all individuals should have equitable access to affordable, high-quality health care. Accordingly, we have significant concerns that establishing a BHP in Oregon would do more harm than good through its impact on enrollment, premiums, and provider rates.”

Feds rejected efforts to curb premium cost hikes

To lessen the impact of premium hikes on people who don’t qualify for the Basic Health Program, the state's task force directed state staff to pursue two options intended to curb the increases.

The federal government, however, rejected both ideas. One would have set up a system in which the state paid carriers a flat per-member fee to reduce the premium hikes, but it would have “created too many winners and losers,” Sweeney told another advisory group, the state Health Insurance Marketplace Advisory Committee, on May 25.

The other idea floated by the state was to ask the federal government to give Oregon a special, higher-than-normal level of subsidy for the program, helping reduce the premium hikes.

Despite the failure of the task force’s premium protection plans, state officials argue that the impact of the premium hikes will be lessened because they won’t all hit in the first year. Some people will be slow to enroll in the new program — so if the critics are right that the state’s projections are overly optimistic, this delay could give decision-makers time to change course, state officials say.

The likely phase-in “slows down the premium increases and potentially gives state policymakers time to respond if the impact differs from projections,” Sweeney told the Oregon Health Policy Board on June 6.

The failure of efforts to limit or “mitigate” the premium impacts, however, has sparked renewed opposition among health insurance carriers. In a comment on the plan, Cambia Health and its subsidiary Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon faulted the state for rejecting federal officials' counterproposal for limiting premium hikes, an idea that could have cost the state $140 million.

“We are concerned about the state dismissing these options because of the financial risk to the state, while effectively passing the financial risk to individual Oregonians, who may lose or reduce coverage as a result.”

“Cambia is concerned that the state and CMS have moved away from the promised mitigation,” Mary Anne Cooper, Regence’s director of government relations wrote. “We are concerned about the state dismissing these options because of the financial risk to the state, while effectively passing the financial risk to individual Oregonians, who may lose or reduce coverage as a result.”

Insurers, of course, stand to lose money when the program is launched, so their opposition might seem unsurprising. But even supporters of the idea had strongly urged the state take steps to curb the premium impacts on people who don't qualify for the new plan, noting that higher premiums will cause people to reduce coverage, potentially hurting their finances and access to care.

One state simulation suggested more than 7,000 could do so, meaning "their deductible could rise thousands of dollars, subjecting them to more unpredictable and higher amounts of cost-sharing," advocates with United States of Care, a national reform group, wrote last October, adding that while the task force was charged with designing the program, "it is also charged with developing mitigation strategies for impacts on the individual market."

Study casts doubt on task force’s plan

On the eve of the public comment period opening on the program, a highly respected Washington, D.C., think tank that has long been an advocate for progressive health reforms issued a study with the Urban Institute casting doubt on whether other states can easily achieve the Basic Health Program success Minnesota and New York enjoyed.

New York in particular is held up as a model for Oregon, as the eastern state has managed to build up a surplus of revenue over time with its Basic Health Program. The surplus allowed administrators to give a needed boost to provider reimbursement rates.

In Oregon, state officials and advocates hoped that surpluses could similarly be used here to increase reimbursement rates for providers who take the new plan. The state’s task force echoed supporters of the plan in calling for reimbursements to be higher than under the Oregon Health Plan.

But the report Urban Institute issued in April with experts from the Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms found that New York’s surpluses resulted from the state’s particular laws and circumstances and may not be achievable by other states.

“The BHP has shown success in providing affordable and accessible health coverage for low-income consumers in both New York and Minnesota, but it is unclear whether other states can replicate this success,” the study’s authors wrote.

Specifically, New York’s insurance premium laws mean that its Basic Health Program receives a significantly higher level of federal subsidies than other states would under federal rules. The studies’ authors called New York’s special situation “a strong recipe for a surplus.”

States that are home to high marketplace premiums are the ones best situated to operate a sustainable Basic Health Program, the study found. That’s because they receive higher federal subsidies closer to those received in New York. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Oregon is not one of those states: Its premiums sit squarely in the middle of state rankings.

Another key factor to make the numbers pencil out without contributing state spending: Paying providers roughly the same cut-rate reimbursements they make under Medicaid, a standard Oregon had hoped to exceed.

Asked to comment on the study, state officials downplayed its significance, expressing confidence in the actuarial calculations they commissioned that found federal subsidies would cover the Basic Health Program’s costs.

"The Task Force discussed potential investment strategies should enough of a surplus materialize, but did not determine or recommend that implementation of a BHP should be contingent on achieving a substantial surplus," according to a statement from the Oregon Health Authority.

Other options lacking to curb premium hikes

In the absence of a higher level of federal subsidies, state officials could explore other options to offset the premium hikes in Oregon. But some options are considered unrealistic or could undermine the program’s success.

The state could supply its own funding to curb the premium hikes, for instance, but that option won’t be available for years, and would likely require substantial expenditures from the state’s General Fund. Or, officials could charge small premiums for the Basic Health Program, an idea that supporters of the plan said should be avoided to ensure the most enrollment.

There are complications even for those unappealing options. For one, the impasse at the Oregon Legislature means that a $748-million budget item intended to help fund the transition to the Basic Health Program has not won final approval. Of that figure, $637 million would be federal funds.

Not only that, but a bill intended to authorize state officials to purchase a more versatile state-based marketplace, rather than use the federal one, also got caught up in the impasse. That bill could have had a new marketplace up and running in 2027, making it easier to address the premium hikes — albeit years after they hit.

In any event, the possibility of a state marketplace as well as uncertainty around future federal subsidy rules make it hard to predict how premiums actually would change under the program, said Maribeth Guarino, a health care advocate for the Oregon State Public Interest Research Group, which supports the new program. “The health care industry is never stagnant, so it’s hard to predict the effects on premiums when there are still decisions to be made,” she said.

Health board hears impacts

In the June meeting of the Oregon Health Policy board, the state’s health policy analysts working on the plan, Sweeney and Laurel Swerdlow, did not mention the new Georgetown/Urban Institute study or address the differing views of health insurers during their update on the program’s development.

Sweeney went through a set of slides but soon was warned he was running out of time.

One slide shown only briefly listed the assumptions the state’s actuaries used to estimate premium hikes. Sweeney noted that the outside firm expressly requested the assumptions be shared when presenting the projections.

“The actuarial team that put together this analysis really wanted us to make sure that we’re clear about the assumptions used, but we don’t have to spend the time to chat about this right now,” he said.

One assumption on the slide was emphasized in bold font. It said the premium hike projections assumed that “ARPA/IRA subsidies” would continue through 2027.

The line referred to hefty federal marketplace subsidies that are in reality slated to expire in 2025, not 2027. The American Rescue Plan Act authorized them for the pandemic to keep premiums down, and they were extended by the Inflation Reduction Act.

With Republicans having taken over the U.S. House of Representatives, speculation has abounded over whether the subsidies would be repealed, as opposed to being extended as the Oregon projections assume.

Asked about the assumption, state officials said it was adopted to ensure the slides showed only the impacts of the new state program. They said the possibility of the pandemic subsidies going away only strengthens the arguments for setting up a Basic Health Program — which, as envisioned, would offer better coverage than the individual market does.

Because of that assumption, however, the slides shared with the board to depict premium hikes through 2027 did not show the cumulative increases that are expected to pressure consumers — in other words, the full picture that insurers fear will destabilize the health insurance marketplace.

Sweeney summarized the program’s premium impacts by income category, while saying the program was slated to go into effect in mid-2024.

Only about a fifth of people who fell in the 200% to 300% range of federal poverty level would see increases of more than $300 a year, he said. People in the 300% to 400% range would see an average increase of about $480 a year, though “a few folks" would see increases of $1,200 a year or more. People making more than 400% of the federal poverty level would pay an average of about $770 more per year, under the figures he relayed.

When Sweeney wrapped up, the complexity of the dynamics he described could be seen in the board’s subdued response. Only one question was asked, concerning basic understanding of the program. Two other members of the board — a group steeped in health care policy — indicated they weren’t totally sure they understood the presentation.

“Tricky stuff,” said Dr. John Santa, a former Oregon Health Authority official and former health care executive. “I’m not sure I understand all this, but, you know, (am) impressed with Oregon’s effort to maintain (the coverage) status quo.”

“I agree, very complex work,” said Oscar Arana, a nonprofit consultant who serves as chair of the board. “It was hard to really follow. But, you know, we trust the experts.”

Public comment can be emailed to [email protected] or mailed to: Health Policy and Analytics Bridge Program Team Attn: Joanna Yan 421 SW Oak St Suite 875 Portland, OR 97204.

Those who will be taxed for this plan and don't utilize it, should benefit from it in some fashion, such as a tax deduction and write off. Much like a HSA plan.