In the span of a few weeks, lawmakers are trying to turn a looming disenrollment of as many as 300,000 people from the state’s free medical and dental care program for low-income Oregonians into a springboard for major change, setting up a new hybrid health care plan that would cover tens of thousands of people.

The bill has morphed significantly in a short amount of time. And with challenging deadlines ahead, some in the industry say that HB 4035’s authorization of a bridge plan, or Basic Health Plan, may be a step too far.

But supporters, including health reformers, doctors and the Service Employees International Union say it would keep people covered, combat health inequities and address the shortcomings of commercial health insurance.

“Nobody is saying this is going to be easy,” Rep. Rachel Prusak, D-Tualatin/West Linn and chair of the House Health Care Committee, told the Lund Report. “It’s an all-hands-on-deck situation.”

The bill links two major components. First it would guide the state’s post-pandemic eligibility checks for people on the Oregon Health Plan. That’s necessary because a pandemic-sparked federal ban on kicking people off Medicaid whose incomes no longer qualify is scheduled to expire on April 15, when the federal public health emergency expires. When it does, states, including Oregon, will need to determine who qualifies to remain enrolled and who does not because their income increased.

Second, the bill would aim to find a landing place for some of the people disenrolled — an estimated 55,000 of them — by launching a so-called Basic Health Plan. This “bridge plan,” as officials have dubbed it, would essentially layer on top of the Oregon Health Plan, using the same delivery system and covering people in the income range just above Medicaid limits.

Coverage in the bridge plan is intended to be free or low cost. It would be available to individuals with an annual income of $18,754 to $27,180. For a family of four, that range is $38,295 to $55,500. That represents 138% to 200% of the federal poverty level.

But there are a lot of factors to consider for the ambitious bill. In order for Oregon to pull it off, the state will have to navigate considerations that include health equity, technology, federal negotiations and some tricky policy questions. Here’s a breakdown based on interviews, documents and public testimony.

Health Disparities

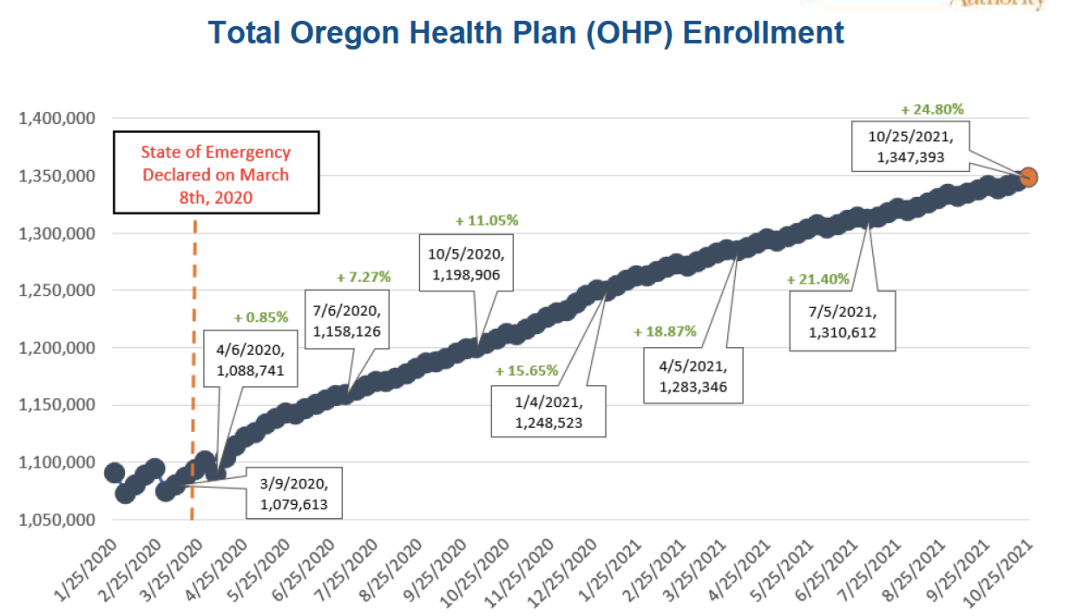

The federal government’s rule blocking states from kicking people off Medicaid has propelled two years of huge growth in Oregon Health Plan membership, propelling it from 1.1 million to nearly 1.4 million people.

State health insurance surveys show that the portion of people with coverage in that period has particularly increased for people of color, suggesting the resumption of eligibility checks will reverse those gains and increase health disparities, supporters say.

While many of those disenrolled will have access to job-based employment, many will not. And while people in the income range targeted by the Basic Health Plan would have access to large subsidies, they still pay an average of $84 a month, bill supporters say. That doesn’t include co-pays and other cost sharing.

”These monthly costs may be too much for Oregonians working full-time in a low-wage position,” wrote An Do, executive director of Planned Parenthood Advocates of Oregon.

Felisa Hagins of SEIU’s Oregon State Council wrote that disenrolling people in that income range would hit the working poor hardest, including many SEIU nursing home and homecare workers, who “are disproportionately people of color.”

Households with earnings that fell into the targeted income range in 2019, before Oregon Health Plan enrollment ballooned, included nearly 369,000 non-elderly Oregonians, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey in 2019. About 14%, or 53,000 of them lacked health insurance of any type.

Short Timeline

The eligibility checks are scheduled to resume when the public health emergency declaration issued by federal health officials expires. The federal government then allows states 12 months to conduct them all, to determine who now makes too much to qualify.

Under this bill, the state would extend that period to the end of 2023 for people in the BHP income range. But still, the bill recognizes that a lot must happen to make the eligibility check process run smoothly — including navigators, outreach and more to ensure that everyone undergoing the checks responds to necessary questions in a timely way; additionally, the bill lets the Oregon Health Authority relax many of its requirements to discourage the disenrollment of people for technical or paperwork reasons rather than eligibility.

Then there’s the task of erecting a bridge plan. Currently, only New York and Minnesota have set up a Basic Health Program. To obtain one, the state must obtain a federal waiver from the federal government, and hope that federal Medicaid officials cut the usual timeline of more than a year. Officials say the feds have promised to move fast.

The bill sets up a task force of legislators, state policy officials and advocates to frame the proposal and authorizes OHA to apply to the federal government for permission.

State officials also want to align benefits so people don’t have to search for new providers or experience interruptions in care.

Trying to handle either the eligibility process or the new health plan would be demanding on its own, but both at the same time? Very risky, critics say.

Providers have widely praised the effort to keep coverage going for Oregonians who would otherwise get bumped off the Oregon Health Plan. But some struck a note of caution about the risks of ramping up a complex program in a short period of time.

Executives with Providence, Oregon’s largest provider, said they support a “true, short-term bridge program” to cover people who are bumped out of the Oregon Health Plan until they can transition to subsidized marketplace coverage. But they said the plan envisioned in the bill risked hurting people making incomes higher than the Basic Health Program is intended for, and urged the task force to study it.

“Rushing a permanent program through the short session, that has only been conceived of in the last few weeks, will have unintended consequences,” warned William Olson, CEO of Providence Health & Services—Oregon and Don Antonucci, CEO of Providence Health Plan, in written testimony.

“We should be very careful about attempting to build a brand new program without enough time, especially while other coverage options are available,” wrote Cheryl Nester Wolfe, President & CEO of Salem Health.

Costs Steep, Many Unknowns

Legislative budget analysts anticipate a cost of $584 million in state and federal funding over the next two years, which includes expanded technology and hiring more than 100 state employees who will manage cases, staff a call center and other tasks to help avoid interruption of care for people who are disenrolled, according to a state budget estimate.

Of that total, $161 million of that would be from the state general fund and almost $424 million would come from federal funding, according to preliminary state estimates.

Those costs could change and depend on when the federal public health emergency ends.

Those costs anticipate and include the following items:

- Costs of the redetermination process and work, estimated at $388 million for this biennium. Nearly $97 million would come from the state general fund. Federal funding would cover the remaining $191.5 million.

- About 100 additional employees in the health authority and Oregon Department of Human Services. These include caseworkers, call center workers, marketing and outreach people, managers and others.

- Those costs include the process of getting the redeterminations done and the system set up. State officials have the goal of providing coverage through federal dollars once the program is set up. An estimate of the federal price is unavailable.

Once the Basic Health Plan is set up, state officials say, there will be start-up costs. The goal, however, is to have the cost of care covered entirely with federal dollars diverted from funds that normally would be distributed in the form of premium-reducing tax-credits to qualified individuals on the state insurance marketplace. The health authority is still negotiating that with the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The costs of the 2023-2025 biennium are estimated at nearly $300 million. That’s $131.3 million in state general funding and nearly $168 million in federal funding.

Technology Concerns

Given Oregon’s history with technology, systems, some are raising red flags about the need to make sure that part of the work stays on track.

Nearly a decade ago, the $300 million Cover Oregon project was intended to set up a state-run exchange but the resulting system never worked right and had fatal flaws. Following months of chaos and uncertainty the project was scrapped in 2014 and Oregonians were forced to start enrolling on the federal marketplace.

Now state leaders face a different set of challenges. The state’s new unified ONE eligibility system — which is key to the bill's plans — was wracked with problems during development, to the point that the state considered scrapping that project also. And even today, though it is up and running, advocates say the system is imposing lengthy delays for people trying to enroll.

“Please make sure that the eligibility system works,” wrote Carol Greenough in testimony, citing the experience of her senior brother, who has Down Syndrome and medical problems. She said the process of re-enrollment took seven months to iron out, and included repeated notices about a cut-off of benefits using language she described as “alarming.”

Hagins, the SEIU official, wrote that the ONE system is a “bottleneck”with “kinks to work out,” adding that “Otherwise, people will lose coverage while facing horribly long wait times and delays.”

Jeremy Vandehey, the health authority’s director of policy and analytics, said the state’s ONE system already has the ability to process redeterminations, as that’s a normal part of the Medicaid eligibility process. There will be some changes to give people more time to respond and put out more reminder notices to people, he said.

State officials point to improvements that will help during redeterminations, such as an overall of income verification tools to reduce the amount of verification needed from recipients and redesigned renewal notices. Other improvements will allow the state to process applications more efficiently.

Meanwhile state officials are working with federal counterparts to understand the Marketplace technology requirements for a Basic Health Plan. However, it is likely that Oregon could start a plan without simultaneously starting a state-based marketplace technology platform, Vandehey said.

The health authority and Oregon Department of Human Services would also need to make changes to eligibility guidelines and other systems to launch the plan.

Policy Questions Remain

The legislation had initially included plans to advance the state’s work on setting up a public option plan

Public option is essentially a state-sponsored insurance plan for people who lack or can’t afford commercial health insurance coverage and don’t qualify for Medicaid or Medicare. It’s different from the state’s planned bridge program because it would be available to people who earn more.

The current version of the bill doesn’t call for a public option.

Prusak said the timing of the redetermination work and the state’s lack of a state-based marketplace made a public option unworkable for now. But the conversation around that issue needs to continue, Prusak said.

In part, the problem is that the Cover Oregon project failed, and the federal marketplace is not easily adapted to the state’s needs under a public option.

“We have to have a state-based marketplace to make that work,” Prusak said. “We are not there.”

This session’s legislation – even without the public option – is necessary with the pending work of redetermining coverage of 1.4 million Oregonians, Prusak said.

“We knew that we had to address that, especially since we didn't have a state-based marketplace,” Prusak said.

Advocates hope the legislation becomes a launching pad that encourages more ambitious plans like the public option to make headway in future sessions.

“Ideally in a perfect world, this would also include the public option and we would have time to build it out,” said Maribeth Guarino, a health care advocate for OSPIRG, which is part of a coalition backing a public option plan.

“I think that this bridge program is a good first step and it’s an opportunity to test the waters by putting out a project like this,” Guarino said.

It’s also unclear if the 34,000 people in the Basic Health Plan income range that currently get subsidized health coverage through the marketplace would be required to switch to the new plan.

Dental Care Unclear

There’s a degree of uncertainty about the full scope of benefits the program would have compared to the Oregon Health Plan. For example, Rep. Cedric Hayden, R-Roseburg and a dentist, has asked for the plan to include dental benefits, which is a provision of the Oregon Health Plan.

The amendment in the works will have language that encourages dental benefits without explicitly requiring it.

“I have been making the argument with OHA that if we’re going to go forward with a plan like this, that dental benefits should just be part of the equation,” Hayden said in an interview.

He said he’s grateful that dental care is at least mentioned, but would like to see dental benefits guaranteed with stronger certainty.

Hayden said it’s important that people have continuity of care with their providers so they don’t have disruptions in health care.

Prusak said she added dental representation to the task force that works on the plan, adding that the dental benefits deserve to be in the conversation as the group looks at the costs of everything.

“Is dental going to be that thing that somehow people walk away and say, ‘No way?’” Prusak said. “I would hope not. A lot more people want dental, but you just never know because everything's going to start to add up.”

Lawmaker Views

Prusak, also a nurse practitioner, said she appreciates the concerns of various health care groups and advocates, but said the state recognizes the enormity and complexity of the task ahead.

“It’s going to be challenging,” Prusak told the Lund Report. “That’s why we’ve been convening groups as big as 30 stakeholders a few times a week to try to figure some of this stuff out.”

Asked if the state’s ONE System is up to the job, Prusak said the extra coordination throughout the system will be key. It’s going to be “navigators on steroids” is how people are describing it, Prusak said.

That includes navigational help for coordinated care organizations, which the health authority contracts with to provide Oregon Health Plan coverage through their networks of providers.

An amendment to the bill is in the works and could be released this week. It directs the health authority to establish a process for redetermination by July 31. That’s an extension from the earlier deadline of May 31.

Prusak said the goal is to extend the planning work out to give the task force time as far as possible without losing federal Medicaid matching funds.

“If we lose that, then we're going to have to work toward setting it up on our own for a period of time and we don't get that same match and that’s what we're trying to avoid,” Prusak said.

You can reach Ben Botkin at [email protected] or via Twitter @BenBotkin1.

If we had Medicare for All, this would not even be an issue. It is time to adopt real health care reform in the form of Universal Health Care whereby no one would have to worry about losing their health care coverage. Everybody In, Nobody Out!