Indigenous-language speakers are a growing population in Oregon, raising the demand for credentialed interpreters for health care. And yet more are speaking languages for which interpreters can't get approved.

As a result of the gaps, advocates say, patients sometimes can’t receive timely treatment and providers at times can’t find someone qualified to speak to them — jeopardizing their care and creating fear and anxiety for all involved.

Formerly uncommon Indigenous languages are becoming more common in Oregon, creating greater need of interpreters for languages from Mexico and Central and South America, according to Pueblo Unido, which facilitates the Collective of Indigenous Interpreters of Oregon.

Now, the group is hoping to secure $1.5 million through House Bill 2976, currently in the Legislature’s budget committee, to add languages to its model for accreditation for Indigenous language interpreters. But to do that it will have to overcome a worsening economic forecast facing lawmakers.

“In the past few years, new or other indigenous languages have come to the fore of those most frequently requested, even surpassing those that traditionally were on the top three or four,” said Cameron Coval, executive director for the Portland-based advocacy and legal services nonprofit Pueblo Unido. More people need interpreters who speak Mam, Chuj and Akateko — spoken across Guatemala and Mexico, Coval said.

‘Catch-22’ as Oregon’s indigenous needs grow

Drawing on court and migration documents, Pueblo Unido now estimates that there are more than 50,000 Indigenous language speakers living in Oregon — up from the 35,000 estimate from just two years ago when the organization first secured state funding to develop its accreditation process.

In testimony to the House committee in March, Coval called the existing interpreter situation a “Catch-22”.

With few exceptions, credentials are required to provide interpretation services. To obtain that credential, an interpreter often must pass a formal language proficiency exam. But these proficiency exams don't currently exist for many Indigenous languages. The lack of proficiency exams means interpreters can’t be included in interpreter registries — and organizations and providers that fail to use credentialed interpreters can be fined.

Oregon already makes it harder to become a credentialed interpreter than in other states, causing challenges for health care organizations that serve low-income people. Coval echoes state reports that say without access to quality interpretation services, people struggle to receive life-saving medical care, cannot access basic needs, and are unable to fully participate in their local communities.

Other testimony from interpreters with Pueblo Unido recounted situations where the lack of an Indigenous interpreter meant long delays in care, to the detriment of the patient’s health, and additional resources spent on urgent care that might have been avoided.

Overseas outsourcing a threat to care, Legacy says

Legacy Health leaders have come out in support of the bill, citing struggles to find in-person interpreters who speak Indigenous languages of Mexico and Guatemala. At times, they have to rely on phone interpreting companies who often outsource these languages overseas, which can lead to emotional stress, frustration, and fear for patients and hospital staff in emergencies.

Interpreters are needed not only in health care environments, but also education, labor and court situations. The proposal in HB 2976 has garnered the support of labor organizations, the Oregon Farm Bureau, and the Oregon Judicial Department, which has documented the increased need for Indigenous language interpreters.

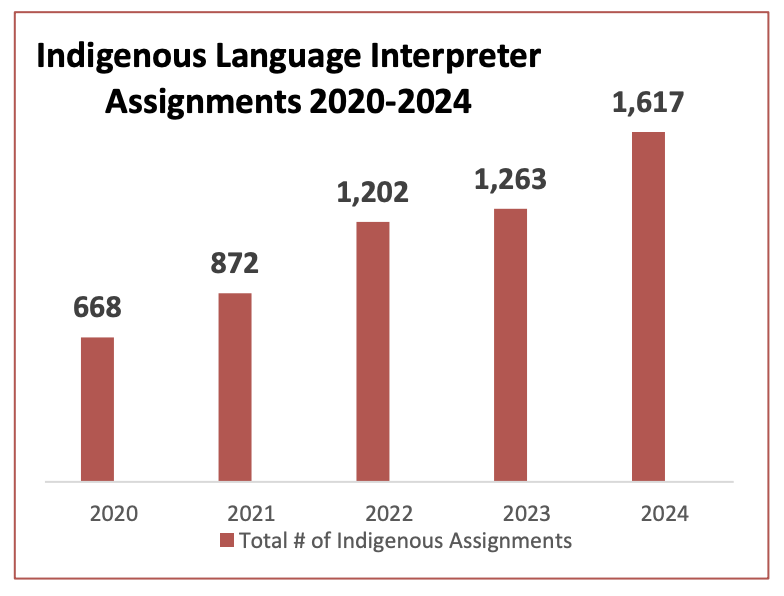

Figures from the Oregon Judicial Department show that from 2020 to 2024, the number of Indigenous language interpreter assignments have increased by an average of more than 25% each year. Mam, an Indigenous language from Guatemala, is in the top 10 of interpreter-requested languages for OJD. State statute requires the use of qualified interpreters in order to protect the constitutional rights of individuals who do not speak English in administrative and court proceedings.

Funds would add languages

The money would be used to develop three language proficiency evaluations for now-commonly spoken Indigenous languages in Oregon, including Mam, and to support recruitment, retention, and coordination of a qualified Indigenous interpreter workforce.

Coval said the impact of having accredited Indigenous interpreters will be “enormous.”

“Without that credential, they don't have a career pathway to pursue interpretation,” Coval told The Lund Report. “By offering the opportunity for interpreters to obtain credentials, just like an interpreter of any other language, we're creating this career pathway, bolstering Oregon's business interpreter workforce, who can then better serve our state entities like the Oregon Health Authority and its partners, or judicial departments and our other public benefit service providers.

“I don't think we can overstate the impact of making yourself understood and being able to understand what somebody’s sharing with you in all of life settings,” Coval said.

It is ridiculously difficult and expensive to get well qualified interpreters credentialed in Oregon. There are native speakers who've worked in healthcare for years who are still required to spend hours of time taking classes (taught in English) on how to interpret when they all do it nearly all day already in their jobs. Why isn't their a 'challenge' test they can take instead of having to do the classes? Once they are credentialed, why do they need to take (and pay for) continuing education hours instead of just submitting the amount of time they interpret? Why is proof of a high school diploma always required when many folks who might not have been born in the US have access to theirs? Each situation needs the ability to be vetted and approved in order to increase language access. Right now, it seems like it is more important to make money for the 'training and testing' companies than it is to increase the number of certified/qualified interpreters. Additionally, not all CCO's pay for interpreters who are in the database. CareOregon refuses to pay for anyone not on their inhouse approved list (a policy predating the HCI database requirement)....and they will not add practice-employed HCI interpreters. This means practices cannot get paid for a service REQUIRED by law. Complaints to CareOregon and OHA go nowhere. It is also frustrating that Medicare and Commercial payers are not required to help cover the cost. When a practice averages 65% of visits in a language other than English, stating interpreters are just 'the cost of doing business' is completely wrong. Commercial payers should be required to cover this cost for the people they get paid to serve. If not the whole cost, at least the single unit required by Medicaid.