This article has been updated to incorporate addiitonal reporting.

Both sides of the debate around Oregon’s drug decriminalization law, Measure 110, have marshaled numbers that show why Oregon should, or shouldn’t, go back to criminalizing possession of small amounts of illicit drugs such as fentanyl and methamphetamine. But their statistics are often used out of context or misleadingly.

The situation brings to mind the old adage, “There are three types of lies: Lies, damn lies, and statistics.” So what is the truth? Here’s a breakdown of some of those statistical claims and study findings, and where they fall short.

Fatal overdoses in Oregon are skyrocketing

Earlier this year the business-backed coalition hoping to recriminalize possession of hard drugs, calling itself “Fix Measure 110,” released a video that flashed a quote from a March 2023 Lund Report article that read “Drug-related deaths among teenagers increased faster in Oregon than anywhere else.” But the video’s producers omitted the part of the sentence that stated the increase was “between 2019 and 2021.” The quote was misleading because the video blamed Measure 110 for the trend, but the law didn’t go into effect until February 2021. Asked about the misleading use of the quote, the campaign removed it from the ad and replaced it with another quote focused on skyrocketing youth overdoses.

The new quote was also used misleadingly, as the article referenced a growth rate that began in 2018 — the same period that coincided more closely with fentanyl’s proliferation than Measure 110’s implementation, despite what the campaign’s video suggests.

It’s true that fatal overdoses are skyrocketing in Oregon, but the state is not alone.

Fatal overdose rates in other states have skyrocketed, too

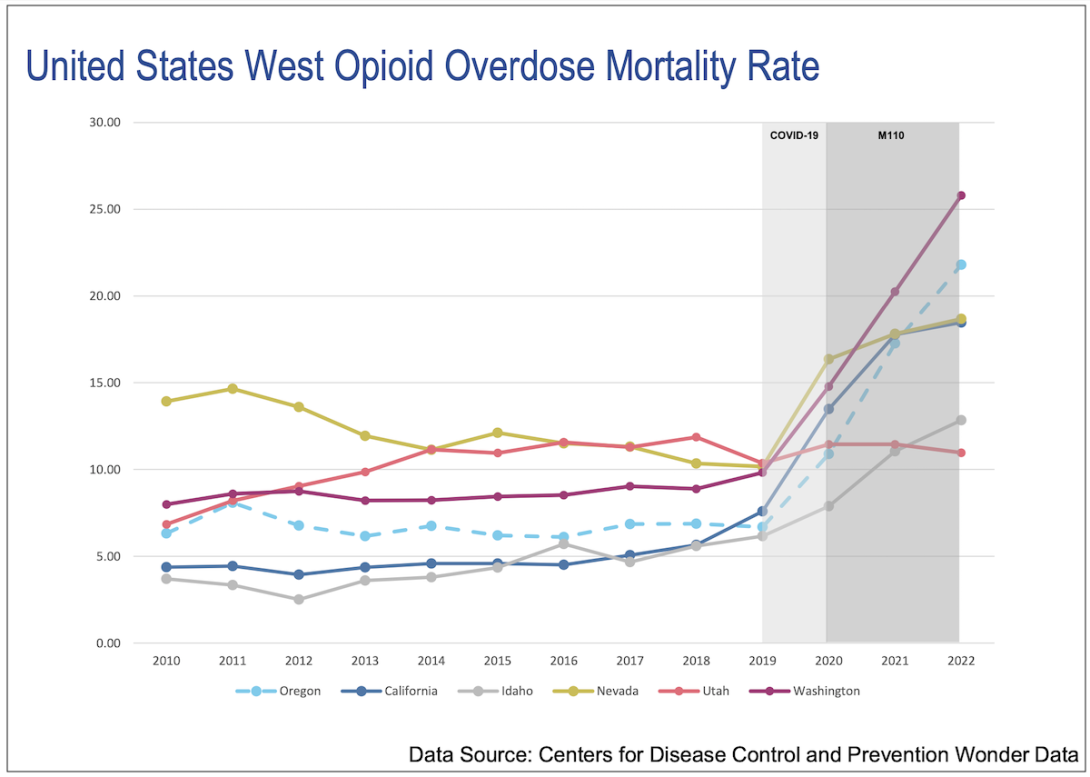

Federal overdose data shows that overdoses began to rise in the Northeastern, Midwestern and Southern regions of the U.S. about 10 years ago, as fentanyl began to contaminate the drug supply across those parts of the country. But the drug didn’t proliferate in the West until about 2019. Then, as the overdose death rate shot up in Oregon, it also shot up in other states where fentanyl was simultaneously increasing in the drug supply for the first time, including Washington, Colorado and New Mexico, according to a federally funded analysis from Brown University.

That analysis was shared at a “Measure 110 Research Symposium” in Salem on Jan. 22. In attendance were Measure 110 proponents, members of the public and state lawmakers. Alex Kral organized the event. He’s leading a research project on Measure 110 for RTI International, a not-for-profit corporation that has provided research and support for a wide range of organizations, including for drug decriminalization, public health, pharmaceutical industry marketing, and development initiatives abroad. He’s also a board member of the National Harm Reduction Coalition, an advocacy group. Harm reduction, the driving philosophy of Measure 110, is a term used for approaches thought to minimize risks and harms to individuals using substances such as meth and opioids.

“The rest of the country got fentanyl in 2013, 2014,” Kral told The Lund Report, “And so their numbers started increasing hugely, much earlier than they did here.”

He presented these trends at the research symposium, where he argued that overdose death rates in Oregon have been on the same trajectory as neighboring states like California, Nevada and Washington before and after Measure 110 took effect in 2021.

But Oregon is skyrocketing faster

While Kral, the pro-harm reduction researcher, said the recriminalization side is using numbers out of context, Kevin Sabet, a former White House drug policy advisor who worked for Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama contends that the data visualization Kral prepared for the symposium downplays the recent jump in Oregon.

“By stretching the graph back to 2010, they minimized the post-110 increase,” he said in an email. “A 2019 to 2022 graph would've better illustrated the rise in Oregon and would’ve been more relevant to M110. They also didn’t write out percentages or numbers, instead opting to bury the trends in lines on the graphs.”

He cites percentages using CDC data that Oregon had a bigger jump in opioid-involved overdoses than any other state between 2020 and 2022, doubling in that span.

Kral's graph comparing states appears to show the Oregon rate climbing faster than other states in that span as well.

This, Sabet argues, shows that Measure 110 took the harm reduction philosophy too far, at the expense of the “greater community.”

Others, including people like Charles Fain Lehman of the conservative Manhattan Institute, have analyzed the same sets of numbers to conclude decriminalization has increased fatalities in Oregon.

Kral says that technique doesn't account for the timing of fentanyl's arrival.

Oregon’s overdose rate is still lower than many states

While overdoses among Oregonians of all ages have surged in recent years due to fentanyl, Oregon’s overdose rate sits in the middle of the pack among states. With 29.5 deaths per 100,000 Oregonians in 2022, the state ranked 29th nationally. West Virginia, where recreational marijuana is still illegal, ranked highest, with 75.9 deaths per 100,000 residents.

And while the number of teenage drug deaths in Oregon increased more than fivefold since 2018, to 26 in 2022, the claim made in the “Fix Measure 110” coalition’s recent video, that “Oregon now leads the nation in teenage drug deaths,” is questionable. That’s because the actual rate of deaths among teenagers 15 to 19 in Oregon was still eighth among states, tied with Arizona, even after that sharp surge, according to the most recent federal data. States with both liberal and conservative leaning approaches to drug policy had higher rates of teenage overdoses than Oregon in 2022, including Washington, Colorado, Kansas and North Carolina.

While this doesn’t mean Oregon isn’t experiencing an overdose crisis, it does indicate that other states — including some that have not decriminalized possession of hard drugs — are suffering, too.

Other factors make it hard to parse the numbers

The problem with trying to draw conclusions is that a lot plays into the numbers, and not just fentanyl.

It’s true that the western United States has seen a “fourth wave” of overdoses due to fentanyl increasingly being spliced into other illicit drugs by Mexican cartels to boost potency and demand, such as by promoting addiction.

But there are other factors, too. Fentanyl and Measure 110 arrived as Oregon’s behavioral health system ranked at the bottom among states.

Already battered by opioids and meth, the pandemic decimated Oregon’s threadbare system further as Measure 110 went into effect.

“Measure 110 is still so new it’s hard to reach any conclusions. You just don’t see things change that quickly.”

Not only that, but an investigation by The Lund Report last year found the state has failed to invest in recommended youth prevention measures and treatment, making them particularly vulnerable to fentanyl’s spread.

And, an investigation this year found the state does little to support school districts in adopting evidence-backed drug prevention measures — or hold them accountable despite a state law requiring robust, research-based prevention in schools.

Another factor that could be affecting the numbers is Oregon’s wide distribution of the opioid overdose-reversing drug naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan. As Measure 110 poured money into harm reduction services and legislators took aim at decreasing overdose fatalities, the state has made the drug more easily accessible. But even so, a White House-funded analysis that compared naloxone laws across all 50 states in 2022 found that Oregon fell behind many other states in terms of laws that allow easier access to the drug across several categories.

Todd Korthuis, an addiction medicine specialist at Oregon Health & Science University, has tracked the numbers closely also. He said he doesn't know of any statistics that could definitively break down Measure 110's role in the state's overdose rate.

"No, I don't think anyone does right now," he said. He added that the arrival of fentanyl in the drug supply "eclipses any current policy analysis" that otherwise would be possible by dissecting numbers. "Any analysis of drug use or overdose deaths should account for changes in the presence of fentanyl over time as the main driver. Otherwise, any change is more likely due to fentanyl trends than any particular policy.”

Consider the source

It's well-known that the "Fix Measure 110" campaign seeking to recriminalize is backed by wealthy individuals and businesses, including people like Nike co-founder Phil Knight.

Other connections have gotten less attention. The New York Times on Monday published an op-ed about Oregon’s decriminalization effort, citing some eyebrow raising statistics. One that jumped out? That just 7% of people surveyed who use stimulants, opioids or both are aware that it’s no longer a criminal offense to possess fentanyl. In other words, it suggested Measure 110 hasn't made drug use more attractive.

What the pro-110 commentary didn’t mention was that the survey was funded by Arnold Ventures as part of Kral's four-year research project‚ just as the recent research symposium in Salem was — on the eve of the legislative session. Arnold Ventures is a closely watched entity that promotes decriminalization and funds criminal justice reform efforts. It gave $700,000 to support the Measure 110 campaign through an intermediary, meaning its name shows up on no state contribution reports, and celebrated the measure's passage. The Times opinion piece quoted Kral without mentioning his funding source or advocacy work.

Kral declined to say how much money he’s receiving from Arnold Ventures to fund his four-year project in Oregon. But a report filed by one arm of the entity showed $893,000 paid out in 2022.

The 7% figure found by the project and cited in the op-ed sparked incredulity among local police officers.

“In my years of experience as a drug investigator and contacting drug users, they all know that drugs are decriminalized here,” said Sgt. Matt Ferguson of the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office.

“It feels like a deflection from what the actual issue is,” said Aaron Schmautz, head of the Portland Police Association. “I’ve never heard a single police officer report that education about the law is a barrier to understanding the consequences of the behavior they’re engaging in. And I've been having conversations (with officers) about Measure 110 nearly every day for a year.”

The survey also seems at odds with an observation made by Multnomah Circuit Court Judge Nan Waller, who's worked for years to keep people out of the criminal justice system. In her mental health court she sees people who think meth is now legal because of Measure 110, she told the Oregon Capital Chronicle: “And that is really unfortunate.”

As far as financial ties, Sabet says that while he's not being funded right now for his number-crunching on the pro-recriminalization side, he hopes it will help generate support for his start-up nonprofit, the Foundation for Drug Policy Solutions — which he hopes to build into a counterweight to the pro-legalization Drug Policy Alliance.

To Korthuis of OHSU, the debate is not driven by funding, it's about differing but well-meaning beliefs. There is a "philosophical divide" between some Measure 110 proponents who focus on reducing the harms to individuals of drug use, and critics who focus on reducing the harms of drug use on communities, he said.

"The truth is, we really have to have both ... This is a time to double down on public health and reduce the harms both to individuals and communities."

Point of agreement

One thing is clear, Measure 110 has not achieved all its goals — so far.

As Kral’s slides note, Oregon voters supported Measure 110 thinking it would decrease the negative consequences of drug use such as overdose deaths. And as harm reduction proponents wrote in an early study of overdose statistics, “The hypothesis was that removing criminal penalties for drug possession may reduce fatal drug overdoses due to reduced incarceration and increased calls for help at the scene of an overdose.”

That has not happened. Three years after the measure became law, advocates for Measure 110 say the hoped-for reduction in fatal overdoses has not materialized in part because harm reduction hasn’t been fully funded or implemented yet. Critics, meanwhile, say without criminal penalties, there’s scant reason for people to go into treatment — and the Measure 110 campaign’s promises of more funding for treatment have not come true.

Jim Moore, a Pacific University government professor, has been following the issue from afar. His take is that “Measure 110 is still so new it’s hard to reach any conclusions. You just don’t see things change that quickly.”

Looking at the studies, he gets the same take from both sides: “When people claim they know what’s going, they don’t. Because we don’t really know what’s going on, (or) the impact that’s happening.”

He suspects that whatever legislation passes in Salem to modify Measure 110, it will be driven by anecdotal evidence and “whose stories are more powerful.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized what's known about funders of the coalition backing recriminalization. The Lund Report regrets the error.