For years, Oregonians have reported some of the highest rates of substance use disorder in the nation on federal surveys. The opioid crisis is nearly three decades old and use of methamphetamine, long Oregon’s deadliest drug, has not abated. At the same time, the state consistently has among the lowest treatment availability in the country, according to surveys conducted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Fentanyl — a cheap, incredibly addictive synthetic opioid — has made all of those problems much worse.

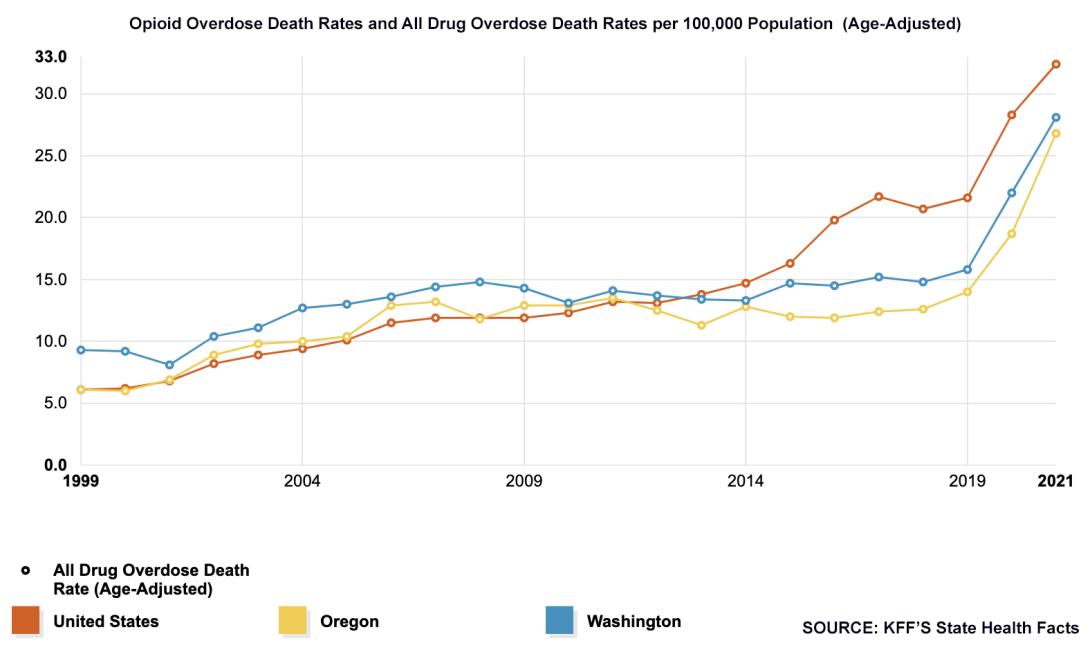

More Oregonians are dying from drug overdoses than ever before. On average, three people die every day from an unintended drug overdose, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

“It’s crazy out there,” said Rick Treleaven, the chief executive officer at BestCare Treatment Services, a recovery services provider based in Central Oregon. “This is a very dangerous time to be a drug addict in Oregon.”

That could be said about most states right now. Oregon was not even among the states with the highest rate of overdose deaths in 2021, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But the size of the problem here has multiplied well beyond the state’s ability to manage it. And the explosion of fentanyl into communities across the state has pushed an already unstable, understaffed treatment system, drained by the pandemic, to a breaking point.

Fentanyl puts both those experimenting with drugs for the first time and longtime users at a much higher risk of overdose than most other drugs. People have died from a single dose, some without knowing they were consuming the drug.

“Fentanyl is increasingly being found in all sorts of drugs on the street so people may not know they’re getting it,” said Dr. Tom Jeanne, deputy state health officer and deputy state epidemiologist.

That’s because illicit fentanyl is often used to make illegal painkillers as well as recreational drugs.

“We are having an overdose epidemic like I’ve never seen and I’ve been in this field for over 40 years,” Treleaven said, speaking at an April meeting of the Opioid Settlement Prevention, Treatment and Recovery board, which is responsible for deciding how Oregon should spend the millions of dollars it’s receiving as part of settlements with drug companies that helped fuel the opioid crisis.

The U.S. Department of Justice summed up the scope of the fentanyl epidemic in an April announcement that it had charged the leaders of a major Mexican drug cartel for their role in importing fentanyl into the United States.

“Fentanyl is now the leading cause of death for Americans ages 18 to 49, and it has fueled the opioid epidemic that has been ravaging families and communities across the United States for approximately the past eight years,” the statement reads. “Between 2019 and 2021, fatal overdoses increased by approximately 94%, with an estimated 196 Americans dying each day from fentanyl.”

For years, China was the main supplier of illicit fentanyl, which people could purchase online and ship — like a package — to an address in the United States. Now, China is the primary supplier of the chemicals used to make fentanyl for drug cartels based in Mexico which ship the drugs into the United States.

Knowing where the drugs are coming from has not been enough to stop their arrival. Despite the Justice Department’s recent high profile indictments, efforts to stop the fentanyl emergency at its source have largely failed. That leaves state leaders and health care providers trying to treat their way out of the problem. And that’s a task Oregon is unprepared to perform.

As of 2021, Oregon’s overdose death rate was in the bottom half of the 32 states that share that information with the CDC. But the fact that the state has so many barriers for people seeking treatment has health officials concerned, especially for the communities of color hit hardest by the rise in deaths.

“Despite similar opioid misuse across all races and ethnicities, American Indian/Alaska Native and Black communities experience dramatically higher rates of overdose deaths compared to other racial and ethnic groups, and these inequities are continuing to worsen,” Rachael Banks, public health director at the Oregon Health Authority, told state lawmakers earlier this year. “These populations have been disproportionately impacted by systemic racism, social-economic-political injustices, and bias.”

Solutions to an international crisis are not easy to come by on the local level. Still, law enforcement and health experts in Oregon agree the state needs to support prevention, enforcement and treatment efforts simultaneously. Right now, most acknowledge, those efforts are falling short.

‘A brief moment of clarity’

On a cloudy spring morning several people gathered on the fifth floor of the Blackburn Center in east Portland, which offers temporary housing to people coming out of detox. The center is operated by Central City Concern, a nonprofit that supports those experiencing homelessness through housing, medical care and substance use treatment.

Most gathered that day were weeks or months into their recovery and were sharing what they were doing to stay sober. One person said caring for his cat helped him stay actively involved in his recovery. Another said he was looking for a new job so he could attend recovery meetings more frequently.

Lisa Greenfield, a peer case manager, leads the group. Greenfield said political leaders and policymakers need to center the voices of those who have lived experience. Right now, she said, there’s still a stigma attached to people battling a substance use disorder and those in recovery.

“Talking to the people who have lived experience and have been through the system” is really what’s needed, she said.

Inside Greenfield’s office there are bins filled with fentanyl test strips, safe injection kits and naloxone, a drug also known by its brand name, Narcan, that’s used to reverse an overdose.

On the wall, there’s a framed photo of her at age 23 — it’s a mugshot.

“That’s me in active addiction,” she said. “I have that framed just to identify with my people to show them that you can recover. I’m just like them too.”

Greenfield said she began using opioids when she was 17. By the time she was 24 she’d had enough. She remembers sitting on the floor of a bathroom, trying to shoot up.

“I couldn’t, my veins were just all shot,” she said. “I know it sounds really corny, but I had a moment of clarity, like just a brief moment of clarity and I just was like, ‘what am I doing?’”

Greenfield said she called her aunt who met her and gave her bus fare to get to detox — a step she had taken before. This time she kept going — from detox, to a housing program that offered medication assisted recovery and ultimately to a job helping others make the same journey. Greenfield has been in recovery for more than seven years.

Throughout the pandemic, she came to work in-person and is now seeing the deadly effects of fentanyl that are seemingly everywhere she looks.

“There’s more overdoses than ever before and so we’ve had to install Narcan,” Greenfield said.

Red metal boxes full of the overdose reversal drug are attached along the walls of the Blackburn Center like fire extinguishers. Greenfield said fentanyl has created an environment where she and her colleagues are “constantly living and working in what is almost a fight or flight mindset.”

“Am I going to find a person overdosed on the street? Or is one of my clients going to overdose? That has been really hard,” Greenfield said. “I have reversed an overdose right outside of my office door.”

The trouble with fentanyl

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that’s 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Doctors use pharmaceutical fentanyl for treating severe pain, such as after surgery or for some patients with advanced cancers.

The illicit fentanyl crisis emerged around 2014, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. It’s part of what some health experts have identified as the third wave of the opioid epidemic. The first wave was driven by prescription pills and the second by heroin.

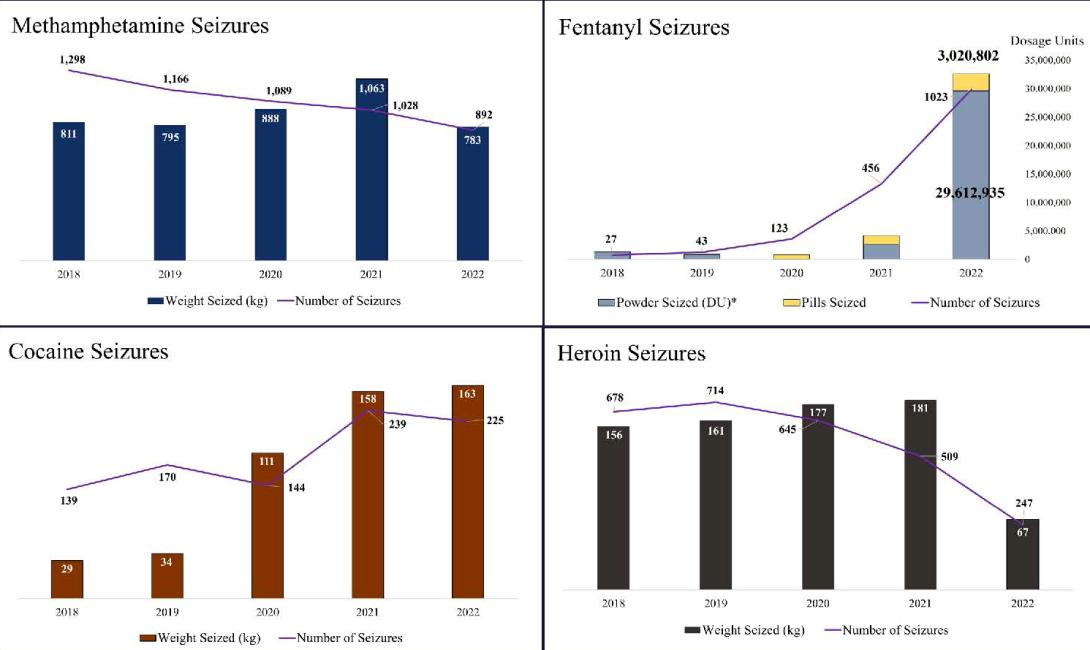

In 2019, a federal drug task force that operates in Oregon and Idaho seized 43 doses of fentanyl. Just three years later — in 2022 — they seized more than 32 million doses.

“Fentanyl is always the big question for everybody right now because it’s completely just crashed onto the scene over the last four years,” said Chris Gibson, executive director of the Oregon-Idaho High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA). The program is one of 33 around the country funded by the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

“Back in 2018, we were looking at fentanyl as nothing,” Gibson said. “It wasn’t here.”

It’s here now, in staggering quantities.

And it’s cheap.

According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, it costs drug cartels roughly 10 cents to produce a fentanyl pill that can sell for $10 to $30. In a recent case out of Oregon, federal prosecutors said a 19-year-old was charged with selling powdered fentanyl as well as hundreds of fake prescription pills that contained illicit fentanyl for $2 per pill.

“The price has really dropped dramatically,” said Steven Mygrant, an assistant U.S. Attorney in Oregon who has spent his career largely prosecuting drug crimes. “Supply, conversely, has skyrocketed. The natural consequence of that is that more people are dying.”

From 2020 to 2022, fentanyl related prosecutions increased roughly 500% for Oregon’s U.S. Attorney’s Office. Meth and heroin cases have become less common, Mygrant said: “What was a two-headed monster, now fentanyl’s king.”

Fentanyl in the United States is mostly produced by two Mexican drug cartels: the Sinaloa Cartel, the country’s oldest drug trafficking organization, and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.

“The Sinaloa Cartel operated as an affiliation of drug traffickers and money launderers who obtain precursor chemicals — largely from China — for the manufacture of synthetic drugs, manufacture drugs in Mexico, move those drugs into the United States, and collect, launder, and transfer the proceeds of drug trafficking,” the U.S. Department of Justice said in a news release in April announcing that members of the cartel had been charged with money laundering, fentanyl trafficking and witness retaliation, among others

Money laundering funds both the cartels in Mexico and those supplying the chemicals out of China, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

It also helps fund the production of chemicals required to make more fentanyl. And it allows Chinese nationals involved in the drug trade to access large amounts of money that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to withdraw due to China’s banking restrictions. Some Chinese nationals have helped the cartels get their profits across the southern border as goods to be sold in Mexico. That allows the cartels to convert their profits back into pesos and skirt tight Mexican banking laws that limit the amount of U.S. dollars that can get deposited monthly into accounts.

Anne Milgram, administrator of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, told a Senate committee in February the agency has mapped “the entire Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco Cartel networks.”

Those networks extend onto American soil.

“We are targeting the drug trafficking organizations and gangs located in the United States that are responsible for the greatest number of drug-related deaths and violence,” Milgram stated.

In Oregon, law enforcement needs more people to do long-term investigations focused on “the ultimate source of supply,” HIDTA’s Gibson said.

“The reality of this is we’re treading water on the enforcement side,” he said. “There’s some really good case work that’s happening, good investigations that are happening. When you don’t have the people that are necessary, you can only do so much with those. And more and more cases are coming in and those start to pile up.”

The trouble with Measure 110

On Nov. 3, 2020, Oregonians passed Ballot Measure 110, making Oregon the first state to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of drugs. The second part of the measure aimed to increase funding for treatment, using money from cannabis tax revenues.

Since its passage, Oregon has struggled to fully implement the law. While possessing small amounts of drugs is no longer a criminal offense, the provision of additional treatment has lagged. Some police and prosecutors say Measure 110 is the reason behind a substance abuse crisis that appears out of control.

“Since Ballot Measure 110 passed, unequivocally, the price of fentanyl has, in Oregon, dropped precipitously, availability has increased exponentially,” Mygrant, the assistant U.S. Attorney said.

And some voters are fed up. A recent poll by DHS Research found nearly two-thirds of voters support bringing back criminal penalties for drug possession.

There’s little debate about whether the expansion of treatment options most voters anticipated would follow the passage of Measure 110 have fully materialized. They have not.

It’s also true that Oregon’s controversial decriminalization law passed at the same time fentanyl was taking the entire country by storm. Supporters argue that while Measure 110 is unique to Oregon, it cannot be blamed for a new wave of the opioid epidemic that has hit every state in recent years.

The spike in overdose deaths also coincided with the coronavirus pandemic, which destabilized the state’s health care systems, further reduced treatment options for substance-use disorder and created a perfect storm of isolation and social disruption that contributed to increased drug use. Overdose deaths spiked nationally during the pandemic.

“It’s important to recognize that the Measure 110 experiment came during a perfect storm,” said Dr. Andrew Mendenhall, CEO and president of Central City Concern. “Measure 110 has funded a lot of important programs in ways that we will start to feel the impact of over the next couple years.”

As those programs begin to roll out and the state begins to spend the approximately $325 million it’s set to receive over the next 15 years as part of the settlements reached with pharmacies and drug companies responsible for fueling the opioid epidemic, Mendenhall is hopeful that services for those struggling with addiction will begin to catch up to the need.

“Let’s not forget criminalizing substance use disorder for the street level consumer who has a substance use disorder … was not a successful strategy,” Mendenhall said.

In hard numbers, experts say it’s very hard to tell what effect Measure 110 is having. For years, Oregon’s Criminal Justice Commission was able to use those charged with possession of a controlled substance to track people as they moved through the justice system. Since Measure 110 went into effect, the state agency that helps develop criminal justice policy no longer has that ability.

“We might have been able to talk about what percentage of folks received treatment previous to 110, at least in the criminal justice system area,” said Ken Sanchagrin, the commission’s executive director.

The data that was available was always imperfect and measured just a subset of people getting treatment, he said, but now that metric is gone.

“What would be necessary,” to track the impact of the new measure, he said, “is for us or for others to partner with public health agencies to be able to track those individuals who are now receiving this new intervention to see what types of resources they’re receiving.”

Since Measure 110 went into effect on Feb. 1, 2021, law enforcement across the state has issued more than 4,700 violations to people with personal possession of drugs, such as meth or heroin, the two most common drugs cited. The citations vary wildly by county. As of April, law enforcement in Washington County issued 65 citations compared to Josephine County where police issued 910, according to data from the Oregon Judicial Department.

When someone is cited, they are given the number to the Recovery Center Hotline, a service run by the nonprofit Lines for Life. They are supposed to call the hotline to be screened for problematic drug use or pay a fine. Proof of the screening is then supposed to be signed and returned to court. As of May 9, the service had received 1,112 calls, but just 189 people completed the screening. Only 37 people — less than 1% — cited for a Measure 110 violation had a substance use assessment signed and returned to the court by the end of April, according to the Oregon Judicial Department.

The trouble with treatment

While a new infusion of cash from the state’s opioid settlements might help get more people into treatment, Oregon has long underinvested in substance use disorder treatment programs, experts say.

“Money was being invested, but the money that was being invested was really out of balance with community need more broadly,” Mendenhall said. “That history of disinvestment has been long standing.”

In 2008, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. It prevented health insurance companies from providing lesser benefits for substance use disorder and mental health treatment than physical health.

“Prior to that it was very mixed and the rates that were being paid were lower than comparable rates for physical health services,” Mendenhall said. “So that reduction meant that programs were themselves barely sustainable in terms of the rates that they were being paid.”

The passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 also boosted support for treatment.

Despite those opportunities to catch up, the state hasn’t.

“The most recent studies are telling us that Oregon has about 50% of the treatment access or treatment capacity that it needs to meet the population health needs of Oregonians more broadly,” Mendenhall said, noting the shortage is in both residential and outpatient treatment.

And there aren’t enough qualified providers to meet the need, even at current funding levels.

Central City Concern, for example, is down roughly a dozen drug and alcohol counselors. That means the organization is unable to serve roughly 400 people a year who arrive seeking outpatient substance abuse treatment.

“We have people waiting,” Mendenhall said. “Substance use disorder is a condition where if people wait, people die.”

And even if they don’t die immediately, he said, people who don’t get help when they are ready for it, may no longer be ready when the help finally does arrive.

Another trend complicating treatment is poly-substance use. Essentially, people are using and becoming addicted to more substances, which makes treatment more difficult.

“Folks are coming in and they’re a lot sicker,” said John McIlveen, State Opioid Treatment Authority, Oregon Health Authority. “Issues are kind of compounding on top of each other and it’s making it more challenging to serve and treat the population.”

There’s also a lack of infrastructure, which includes everything from physical buildings to levels of treatment and support. Some people can go from detox to outpatient while others need detox and supportive housing or residential treatment which is even harder to come by. Treatment isn’t linear. Even in the best circumstances, someone can have a recurrence of use and may need to go to detox again. All of that takes capacity, communication and funding. And if there are also mental health issues at play, there needs to be a systematic way to get those addressed.

“We have to build infrastructure,” said Fernando Peña, executive director of NW Instituto Latino during an April meeting of the Opioid Settlement Prevention, Treatment and Recovery board. “We need to start thinking of builders of the system. Not funders of the system. If we just view ourselves as just funders we will fund what exists.”

And what exists isn’t nearly enough. That’s especially true when it comes to culturally specific treatment and recovery services, whether it be for communities of color or the LGBTQ+ community.

“When you see someone else who looks like you, thinks like you, knows the things that you’ve gone through, either trauma-wise or life experiences and you see on the other end that this person has been successful and has been able to sustain their recovery, it inspires hope,” Amanda Ireland-Esquivel, executive director of Portland-based True Colors recovery, which offers peer mentoring services for LGBTQ+ adults new to recovery or struggling with recovery.

The nonprofit began less than one year ago and has already supported 100 people, Ireland-Esquivel said. Roughly 30% have improved their housing situation and 98% have stayed “crime free,” she said.

Most recovery services programs in the state are based in the Portland metro area, Ireland-Esquival said. She thinks more programs like hers need to exist in rural areas.

‘The difference between life or death’

Solving Oregon’s drug crisis will take more of everything — treatment options, trained professionals, prevention education, time and money.

Not all those things are in place. And yet, many people are working hard to change the current system to better support those in recovery and to prevent future tragedies.

During their time living in temporary housing at Central City Concern in Portland, participants work on securing long-term housing and establishing treatment. About a third of them go into residential treatment, a hospital, a shelter or housing, according to Central City Concern’s data. But participants aren’t required to say what they do next, so the outcome for about half of the people completing the program is officially “unknown,” according to a spokesperson.

Greenfield, the peer case manager, said there isn’t enough coordination and capacity between organizations to be able to get people into treatment — starting with detox centers that she said should be able to accept people “no matter what time of day it is.” She said sometimes people are turned away because they’re full or closed. If people use substances while in the program, they also need to go back to detox, further straining resources. She’d like to see more support for people at every phase of their recovery.

“They can get into detox, from detox, they can get into residential treatment, inpatient treatment. From there, they can get into a supportive housing program,” she said. “If there was just this continuum of care just already in place, I think that we really could tackle some of what’s going on.”

In March, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved naloxone, the generic version of Narcan, as an over the counter drug making it widely available to anyone who wants to purchase it.

House Bill 2395 in the Oregon Legislature, would also make it easier to access naloxone, protecting those who dispense it from liability and also decriminalize handing out drug testing strips in public. Testing strips can help users determine whether a drug, such as cocaine or a fake Oxycodone, contains illicit fentanyl. But they are not without limitations.

In December 2020, Jon and Jennifer Epstein’s son Cal Epstein died from a fentanyl overdose after taking a pill made with illicit fentanyl. He was 18.

Before Cal died he Googled what would be a safe dose of “Oxy” for his weight and whether it might affect medication he was taking to treat his anxiety.

“He made a poor choice in reaching for an Oxy, but he was trying to be safe,” Jennifer Epstein said. “He was trying to make a good decision for himself, and the information wasn’t out there.”

She now works with the nonprofit, Song for Charlie, which aims to provide information about drug use for young people.

A survey the organization conducted in the fall of 2022 found, nationwide, teens weren’t aware just how dangerous fentanyl can be. Only about one-third of high school students understood the risks posed by illicit fentanyl and fake pills.

“They actually listed fentanyl about as dangerous as cigarettes, because they just really don’t know,” Jon Epstein said.

According to the Lund Report, Oregon had the fastest growing rate of 15- to 19-year-olds to die from a drug overdose between 2019 and 2021.

Sharon Dursi Martin, is the principal at Harmony Academy, a charter school in Lake Oswego that’s the first in Oregon aimed at providing an education as well as recovery support for youth with substance use disorders.

“If you can intervene now, they have a power that they can change things and they can bring more people along with them,” Dursi Martin said. “It’s like we keep ignoring adolescents because it’s costly and it’s full of liability. It’s also full of hope. We can save lives.”

Dursi Martin, who is also in recovery, said when adolescents enter recovery, it’s profound.

“They tend to transcend once they have had all this experience and then they stop using drugs, they’re like, ‘well, what do I do now?’ And they have amazing potential,” she said. " They haven’t had all the consequences for the most part, yet. It’s healable and it’s changeable.”

Oregon is slowly moving towards a systemic approach to improve prevention education for kids.

The Epsteins have testified in favor of Oregon Senate Bill 238, which passed the House on May 19 and is now headed to Gov. Tina Kotek’s desk for a signature. The bill requires the state to develop curricula about the dangers of fentanyl and other opioids. School districts are required to teach lessons on the topic starting in the 2024-2025 school year.

Both Epsteins want to see schools, along with public health and public safety become more nimble as the opiate crisis continues to evolve. The Epsteins have worked with the Beaverton School District, which launched an awareness campaign in the spring of 2021 called “Fake and Fatal” to educate students about the dangers of fake pills and fentanyl.

“Right now we’re talking about fentanyl, but … other drugs are coming down the line that may be out there in six months or nine months, or a year from now,” Jennifer Epstein said

The CDC has published materials called One Pill Can Kill that parents, teachers and school districts can use. But she said the entire system, from schools to law enforcement to public health, needs to be able to pivot quicker with messages that range from prevention to harm reduction.

The Epsteins have used their family’s tragedy to bring about new awareness to fentanyl. Now they’re pushing for longer term prevention, to try to reduce the numbers of people affected by substance use disorder.

“The knowledge gap with kids is so large,” Jon Epstein said. “Most youth don’t know about fentanyl — especially in fake pills — and for many youth, knowing could be the difference between life and death.”