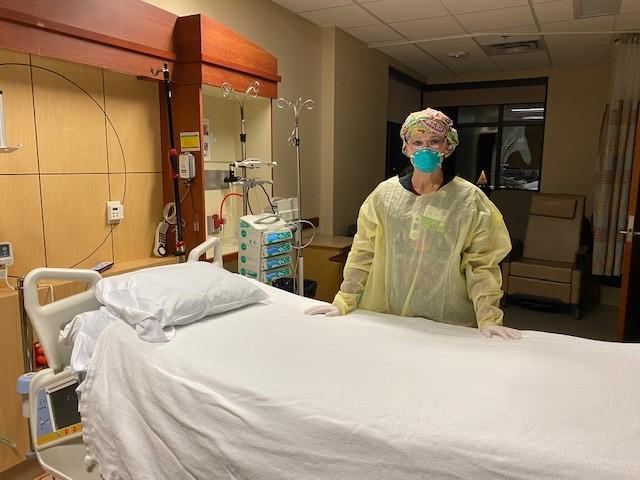

As an intensive care nurse at Sky Lakes Medical Center in Klamath Falls, Julie Bowen is used to patients with life-threatening conditions. She knows how to treat them, and most get better.

But that’s not the case with COVID-19 patients. Their outlook is unpredictable. Some with underlying conditions make it. Others who seem healthy die.

“When you come into the hospital with a heart attack or pneumonia or whatever, we know how to take care of you,” Bowen, a registered nurse, told The Lund Report. “We can fix the majority of our patients. But with COVID, we have no control over what happens.”

The pandemic has forced health care workers in Oregon and across the country to live with uncertainty. They have few tools in their toolbox. They’re exhausted and frustrated. They’ve warned the public to wear masks and take other precautions. Yet even people in Bowen’s own family are virus deniers.

And the cases keep coming.

After a wave of patients following Thanksgiving, Bowen is now bracing for another surge following family get-togethers over Christmas. The death count is likely to grow.

So far, 16 people have died in Klamath County from the infection.

In terms of cases per capita, the county is right behind Multnomah County, with nearly 2,560 per 100,000 people over the 10-month course of the pandemic. That compares with almost 2,920 cases per 100,000 people in Multnomah County.

Sky Lakes, a nonprofit, is the only hospital in the area. As a health care system, it’s part of what the state calls Region 7, which covers much of central Oregon. The area is the only one that ran out of available intensive care beds this month, though just for a day.

Like other facilities, Sky Lakes has created special units with infection control to treat COVID-19 patients. The hospital moved its regular intensive care unit to another floor to create a 14-bed ICU for COVID patients. Another unit, with 10 beds, is for COVID-19 patients who are not as seriously ill.

Bowen said the hospital, licensed for 176 beds, usually treats 12 to 19 patients with COVID-19 at a time. A lack of beds has not been a problem, she said.

“We can always find places and beds to put people,” Bowen said. “The problem is staffing.”

Everyone Works More

At 55, Bowen has more than two decades of experience at Sky Lakes. Hired in 1999 as a certified nursing assistant, she earned a bachelor’s in nursing at Oregon Health & Science University while on the job. She’s logged 17 years as a registered nurse, including 13 in intensive care where she still works caring for COVID-19 patients.

Before the pandemic hit, she worked three 12-hour shifts a week. Now she works the same shift four or five days a week and recently picked up a night shift, something she hasn’t done for two years.

All of her colleagues are putting in extra time, she said. That includes her manager who’s worked the floor to help.

The hospital has hired some traveling nurses but is looking for more, Bowen said. Nurses are in short supply, and special skills are needed to work in intensive care.

Her day starts early. She leaves her home outside Klamath Falls about 4:30 a.m. and starts her shift just over an hour later.

She’s got the routine down: Review the report from the night shift, look at lab results, check which medications are due and start doing the rounds.

“These patients require a lot of care,” Bowen said. “You end up spending a lot more time at their bedside,” Bowen said.

Staff must don and doff protective gear to treat patients. Few patients can sit in a chair. They need to be fed and washed and have their teeth brushed. Feeding alone can take an hour per patient. Some need to be repositioned to prevent bed sores. If they’re on an oxygen device -- such as a BPAP that delivers bilevel positive airway pressure similar to CPAPs, or continuous positive airway pressure for sleep apnea -- they need their mouth swabbed once an hour.

The device “is like sticking your face out of a car window while going a 100 miles an hour,” Bowen said. “It dries the mouth out.”

The care is constantly interrupted by beeping alarms that signal a loose tube or dangerously low oxygen level.

“It’s just all day long running back and forth,” Bowen said. “We’re starting to feel alarm fatigue also.”

She praised the hospital for giving frontline staff support, including bringing in meals so they don’t have to think about food.

“Our managers and directors have been fabulous at making sure we have what we need,” Bowen said.

Nevertheless, the relentless pace is exhausting. “We’re shattered,” Bowen said.

Before the pandemic, Bowen would treat the patient for a day or two and then they would get better and move to another unit. But these patients end up staying days or weeks in the ICU. And then suddenly they might die. The hospital has lost a handful of patients, Bowen said.

“We bond with them, and we bond with their family,” Bowen said. “It takes an emotional toll.”

She said staff have a rule: No one dies alone.

Solace At Home

At the end of the day, she showers, changes into clean clothes and drives home. She and her adult son live in a house in the mountains on 6 acres.

As soon as she arrives, she showers again to help keep her son from catching the virus.

“We have a good routine down for keeping him safe,” Bowen said.

She praised her son for being a good support. He takes care of their German shepherd, Gracie, and feeds their three billy goats. She’s had them since they were young.

They were supposed to keep the weeds in check. Instead, they’ve turned into pets.

“They were hand-raised,” Bowen said. “They’re like 6 years old, and they’re still big babies.”

The property is dotted with pine trees and deer wander through. When Bowen wants to relax she goes for a walk.

She enjoys the tranquility but said she rarely stops thinking about work.

“When I’m not working, I find myself wanting to be back at work to help out the other nurses and also to be with those patients we’ve bonded with,” Bowen said. “We want to give them the best care that we can, whether they live or die.”

Last week was rough, she said. One of her COVID-19 patients, a woman who just gave birth a week ago, had to be resuscitated.

Bowen’s not sure she will make it.

But there is hope. The hospital is vaccinating frontline staff. Sky Lakes received 800 doses of the Moderna vaccine and is vaccinating physicians, nurses and others who work in intensive care and the emergency department. Bowen received her first shot last Monday and will get the second dose in a month. The vaccine requires two doses.

She’s hopeful that the pandemic will start to wind down by April if enough people get vaccinated.

In the meantime, she and her colleagues are hanging on. They’re physically and emotionally emotionally drained.

“All of us have moments,” Bowen said. “But we just try to support each other.”

You can reach Lynne Terry at [email protected] or on Twitter @LynnePDX.