Melissa Jones is banned from downtown Medford. But just a few blocks away, under an interstate overpass, she is a very welcome presence.

Late last month, a municipal court judge upheld a police order excluding Jones, who distributes clean syringes and opioid reversal medications, from the city center for allegedly interfering with officers trying to take a runaway youth into custody.

Friday evening, next to a white van used by her nonprofit, Stabbin’ Wagon, Jones and an associate warmly greeted a stream of grateful visitors who filled plastic sacks with supplies before disappearing into the late summer night.

Three years ago, Stabbin’ Wagon started with Jones handing out harm-reduction supplies from an Ikea bag. Since then, her group has grown quickly and is now slated to receive a $1.5 million Oregon Health Authority grant to set up a respite center for people in crisis.

But news of the grant has sparked backlash from service providers, Medford city leaders and others concerned that a group known for sharp elbows and radical politics is in line for a massive influx of public funds. And the concerns have reached the highest levels of the Oregon Health Authority, which hasn’t yet released the funds Jones was expecting to have by now.

Jones told The Lund Report that city leaders are “ganging up” on her and her organization when they should be offering support. She said her organization’s work is misunderstood and is making up for a behavioral health system that fails too many.

“We are filling the gaps because so many people are getting left behind,” she said. As for the delay in funding, she said, “I don’t understand what the problem is.”

The situation shows the challenges the state faces in setting up new respite centers that advocates say could help people in need. The state plans to staff them with people who, like Jones, have had similar experiences to the people who will be served, while distributing the facilities among regions where those staffers — or services — may not be all that popular.

Contract unsigned, officials concerned

Stabbin’ Wagon was among three organizations selected by the health authority late last year to operate regional respite centers. The centers are intended to be residential alternatives for people experiencing an intermediate psychiatric crisis where they can take a reprieve from their life circumstances while being supported by others who’ve experienced mental health issues, known as “peers.”

The health authority’s selection caused some advocates to raise questions about the qualifications of two small and relatively new nonprofits chosen to run the centers, including Stabbin’ Wagon. Since then, the health authority has paused the contract with one of them, Black Mental Health Oregon, after the state Department of Justice opened an investigation into the group.

Since the grant went public, emails obtained by The Lund Report show local officials have been raising concerns, and Jones said they are trying to spike the funds.

“All of the legitimate non-profits in our area are outraged that she is getting any funding,” Medford City Manager Brian Sjothun wrote to the city’s lobbyist Cindy Robert in an email obtained by The Lund Report. In another email, he called the grant a “disaster waiting to happen.”

Medford Police Chief Justin Ivens replied with one word: “Unbelievable.”

Emails show that Medford Deputy Police Chief Trevor Arnold wrote to Sommer Wolcott, executive director of treatment provider OnTrack Rogue Valley, that he was “absolutely speechless” about Stabbin’ Wagon getting the grant.

Wolcott responded that the health authority has gotten “an earful” about the grant.

“This could blow up into an interesting media sh*t show,” she wrote. “If anything, giving her 1.5 million might help blow things up faster.”

Driving their concerns in part? Fears that the nonprofit would set up a “safe injection site,” a place where people could use drugs more safely without interference by police.

Lori Paris, president and CEO of Medford-based Addictions Recovery Center, wrote to the police chiefs of Medford and Central Point in a March email that “everyone is in shock” over Stabbin’ Wagon getting the grant.

“Community partners are concerned for several reasons, but most concerned that the funds will be used to create a safe injection site,” she wrote.

Paris and Medford police did not respond to a request for comment. Wolcott declined to comment.

The health authority did not immediately respond to questions either. But another email obtained by The Lund Report indicates interim Director David Baden has been tracking the situation and that the agency asked Stabbin’ Wagon for information about the recent arrest of Jones and another employee, which took place at an HIV-testing event. Police were trying to take a youth into custody, and the Stabbin’ Wagon employees allegedly tried to block them.

Ready to start, and speak out

In the face of the backlash, after having initially declined interview requests from The Lund Report, Stabbin’ Wagon is ready to respond to the critics — and has retained a lawyer.

In an interview Friday, Jones said that in June the health authority promised Stabbin’ Wagon the grant money to set up a peer respite center called “Mountain Beaver House.” She said she’s contracted with three people using money donated to Stabbin’ Wagon to set up the respite center. But without a finalized contract, Stabbin’ Wagon has been in a “holding pattern,” she said.

“We’re ready to exceed everyone’s expectations,” she said. “I am so confident about the team.”

An attorney representing Stabbin’ Wagon, Alicia LeDuc Montgomery, told The Lund Report that there is no intention to use the peer respite center as a safe injection site. She also called it “concerning” that Paris may be conflating a peer respite center with a facility for safer drug use.

LeDuc Montgomery said the emails also raise concerns about the motives behind city officials and treatment providers, whom she suggested are targeting Stabbin’ Wagon because they hold different ideological views.

“Why is the city working so hard to prevent a service that won’t even cost the city a dime?” she said.

In the meantime, she said the health authority has still not completed the contract.

Jones didn’t have details about how the peer respite center would operate, saying that she has other staff operating it. But she noted her group’s grant application received the highest score by state evaluators and said the center would follow a model developed by Massachusetts-based Wildflower Alliance. Stabbin’ Wagon’s grant application states that it will pay the Wildflower Alliance $7,400 for 24 hours’ worth of training.

Stabbin’ Wagon was also the only applicant interested in opening a peer respite center in southern Oregon.

The project has the backing of Medford-based Bear Creek Hearing Voices Network, a support network for people who hear voices that opposes the use of forced medication and is skeptical of what it considers the mental health establishment. An unidentified representative for the group told The Lund Report in an email, “We believe in the peer respite model and the urgent necessity of opening one here in Southern Oregon.”

The grant would not be the state’s first for Stabbin’ Wagon. In 2022, it received over $500,000 in Measure 110 funds to support its harm-reduction efforts. Her group had $393,000 in revenue in 2021, according to the most recent tax filings on Oregon Department of Justice’s website.

Community connection

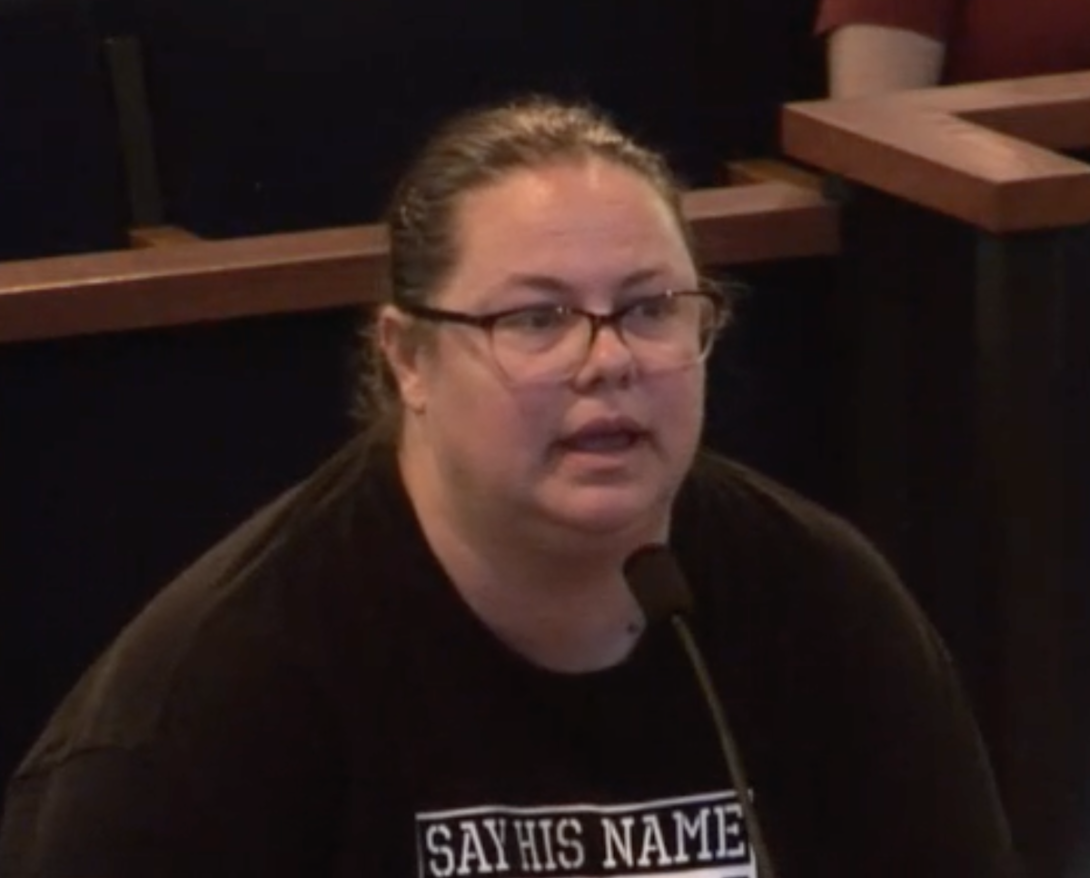

On Friday night, Jones, 46, headed to an area underneath the interstate overpass outside downtown known as “the circle,” for a weekly outreach event by Stabbin’ Wagon.

There, under the soft glow of streetlights, Jones greeted visitors with “Hey friends.” She directed them to her offerings, which included naloxone (both injectable and nasal), condoms, lube, syringes, foil for smoking and test strips to check drugs for the presence of fentanyl.

“Keep up the good work,” said a barefoot man with white hair spilling out from under a backward baseball hat. He commiserated with Jones, saying he was also excluded from downtown.

Bespectacled and wearing her hair in a bun, Jones asks visitors what they’re comfortable with and encouraged them to take Narcan if they think they’ll need it.

“It’s better to have some than none at all,” she tells a middle-aged man who arrives in a powder blue Toyota Corolla.

Just feet away, volunteers with Judi’s Midnight Diner served up biscuits along with mac and cheese from a big metal tray. A man on a BMX bike smoking a cigarette rides up and fills a white plastic bag with supplies from bins next to the van.

A woman with short blond hair and a pink shirt eating mac and cheese embraced Jones. The woman told Jones she now has a room with her own bathroom.

“You deserve it,” replied Jones.

Roots of tension

Social media posts, public records and interviews show that Stabbin’ Wagon has a strained relationship with local police and treatment providers. Several people in the area told The Lund Report that Jones targets those who disagree with her with what they consider to be harassment, both online and in person.

For example, a video online shows Jones confronting Chad McComas, then head of Rogue Retreat, and organizers of a homelessness summit. The group has also had an online feud with Medford City Councilor Kevin Stine over his position on homeless encampments.

Records show that Jones was arrested in 2020 for refusing to leave Medford’s Hawthorne Park as police were clearing homeless encampments. Police also arrested then-Jefferson Public Radio reporter April Ehrlich during the sweeps. Ehrlich’s charges were later dropped.

The arrest of Jones and another Stabbin’ Wagon employee in August occurred after they allegedly confronted police trying to take a runaway youth into custody. The probable cause affidavit states that a crowd gathered around the officers, one of whom stated that he had to push Jones away as she screamed profanities.

“During this altercation I also displayed my pepper spray and pointed it at the crowd in an attempt to get everyone to step back,” reads the document. “At that point someone from the crowd shot me in the face with a water gun and then immediately fled the area.”

Part of the tension between Jones and local groups and officials appears to stem from her full-blown embrace of harm reduction — an approach its practitioners say is intended to reduce the harm from using drugs, as opposed to more aggressively trying to stop drug use.

Dr. Kerri Hecox, medical director of the Oasis Center of the Rogue Valley in Medford, told The Lund Report there is a benefit to Stabbin’ Wagon’s harm reduction efforts, particularly getting Narcan into unhoused populations. However, Hecox said that the approach of “strict harm reduction” is often not effective in aiding people trying to move out of addiction and into recovery.

“People who are dependent on ‘hard drugs’ like meth or fentanyl are really not in a place of free will,” she said. “Substance use disorders literally affect how your brain functions, completely changing your risk-reward pathways. I see people on a daily basis who want to stop using but can’t, their reward pathway won’t let them.”

Jones told The Lund Report, “There are people that just don’t like me because they think I’m an enabler. And they don’t like what I do, and they don’t like my politics.”

A few years ago, following the police killing of George Floyd in 2020, Jones said she began looking into how Black and brown communities are disproportionately arrested and given harsher sentences than their white counterparts.

“I think some police, they’re not bad people, right?” she said. “But their job is in a bad system. I’m not anti-cop, I’m pro-Black-people-being-alive. I’m not anti-cop, I’m pro-people-in-mental-health-crisis-staying-alive.”

Jones described herself as an unfiltered advocate who is clear about her values and will stand up for herself and others, adding, “You can’t be the bully when you don’t have the power or the money.”

She said that she has a community-based approach that honors people’s self-determination while more conventional treatment providers “want to treat people like toddlers.” Jones said her group’s approach makes it well-situated to run a peer respite program

Skeptics have said the new centers will have to interact with police and other nonprofits. When asked about how her peer respite would integrate with other service providers in the system, Jones responded “the one that’s been failing us?” And Jones didn’t rule out that a peer respite operated by Stabbin’ Wagon would never call the police.

“Every single provider in this county either has the police on their board of directors, or partners with them or does outreach with them,” she said. “And we’re one of the very few that refuse to do that.”

Clarification: This article has been updated to clarify Bear Creek Hearing Voices Network stance on medication.

You can reach Jake Thomas at [email protected] or via Twitter @jakethomas2009.

Comments

If the current medical…

If the current medical establishment and the police/justice system had all the answers, we wouldn't need Stabin' Wagon, and they would go away. However. it is beyond obvious that medical care, childcare, homelessness and mental health care are in crisis -- and getting worse. The agencies that are supposedly helping resolve the problem are at loggerheads with each other, millions of $$ are being spent with little tangible result and virtually no accountability.

The only organization that seems to have worked fairly consistently to control alcoholism is a sui generis self-help group. Who knows whether a similar approach would work in drug abuse? The "traditional" treatments have failed, so why not get behind organizations like Stabin' Wagon that use people in recovery to help active users. Early indications are that such an approach might be helpful.

Harm reduction is about saving lives and reducing morbidity -- it doesn't "promote" drug use, but doesn't require people to stop using in order to benefit from the service -- after all, if people weren't using drugs, we wouldn't need "harm reduction"!

SUD treatment and drug interdiction by law enforcement are on parallel tracks with "harm reduction" -- they are all necessary and are not mutually exclusive.

Thank you for covering these important issues in Southern Oregon. On behalf of the Bear Creek Hearing Voices Network, however, we would like to clarify that our group does not "oppose medication."

We are guided by the Hearing Voices Network USA Charter, which allows group participants the "freedom to interpret experiences in any way, not just an illness framework." We also believe that "the person having these experiences is in the best position to decide or discover what they mean, and what they want to do about them."

A great introduction to the Hearing Voices Network is Eleanor Longden's TED Talk called "The voices in my head." The book The Mind and the Moon by Daniel Bergner gives a more in-depth read.