Medical debt often contributes to the financial ruin of Oregonians who file for bankruptcy, suggests a new report from Oregon State Public Interest Group and Frontier Group.

The report, released Thursday, analized nearly 8,000 personal bankruptcy filings in Oregon in 2019. That’s before the pandemic, which has infected nearly 300,000 Oregonians with COVID-19 and killed 3,373 so far.

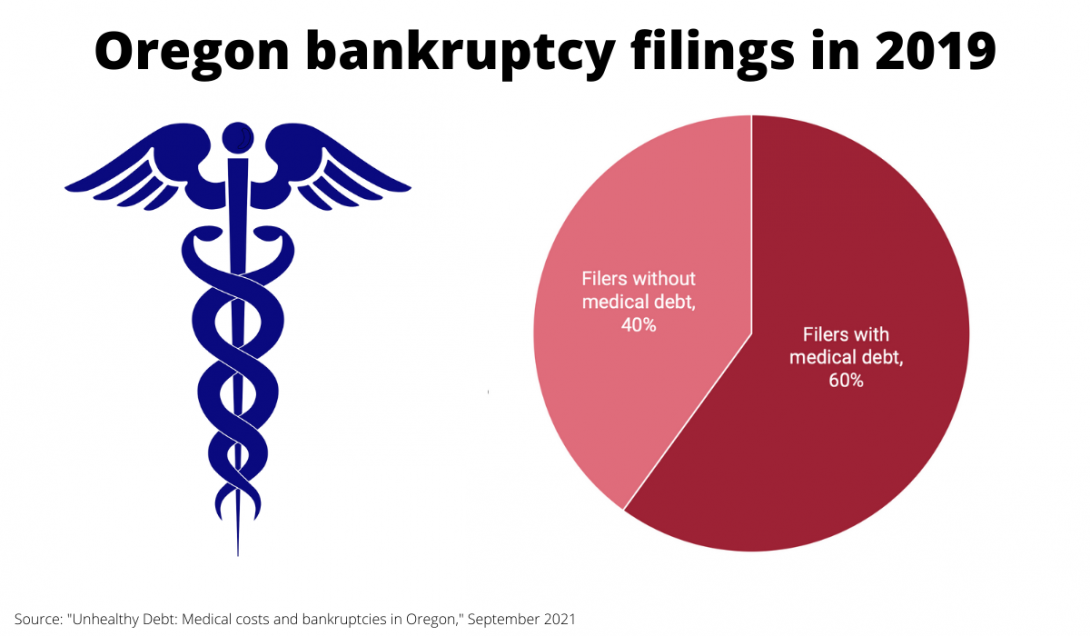

While documents used to compile the report did not disclose the reason each individual decided to file for bankruptcy, they revealed that 60% of filers owed money on medical bills. For 188 of the people who filed for bankruptcy, medical debt accounted for more than half of all the money they owed. The report looked exclusively at Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 filings, which are the most common types of bankruptcy filings for individuals.

The median medical debt owed was about $2,300, but some filers — 155 of them — reported medical debt that was higher than their annual income. About 15% owed more than $10,000, and two individuals who filed for bankruptcy owed more than a half million dollars.

“Medical debt was present in every county where bankruptcies were filed, and in the majority of filings in income brackets up to $100,000 per year,” Maribeth Guarino, a health care advocate at OSPIRG, said Thursday. “This report shows that high health care costs are not a problem limited to a single geographic area or economic demographic — it's everywhere and we have to do something about it.”

The report's authors argued the high cost of health care and health insurance are why medical debt appeared in so many bankruptcy filings. They pointed to health care spending in Oregon that reached $30.7 billion in 2018 — more than $7,300 per person, as reported by The Lund Report. In 2019, health insurance premiums averaged around $450 a month and Oregonians had the third-highest deductibles in the nation, averaging nearly $4,000, according to Oregon Health Authority.

For Caitlin Costello, a Portland State University student, paying for health insurance would have meant sacrificing money she needed for rent, food or tuition when she started on her collegiate path. She said for years she lived in fear of incurring medical debt. Shortly after she got insurance for the first time in eight years, she broke her elbow.

“I was still in the same mentality as before, so I refused an ambulance, I waited almost three hours for family to come get me,” she said over Zoom at the report’s release. “I refused pain medication upon arrival, and during the entire process, anytime they suggested anything I was consistently asking, you know, ‘How much is this going to cost? Is this covered?’ ” Costello said. In the end, the cost of her hospital visit was more than $20,000, and she was responsible for $4,000 of it. She said her medical debt determined how many college classes she could take while she paid it off.

To combat the impact of high health care costs on Oregonians like Costello, the report recommended the state implement a public option health plan that would reduce the cost of insurance premiums and other expenses. Oregon lawmakers passed House Bill 2010 earlier this year, which directs state agencies to create an implementation plan for such an option.

More than one-third of Oregonians reported struggling to pay medical bills, according to a poll conducted by nonprofit research and consulting group, Altarum, earlier this year. Respondents said they covered costs by using up their savings, borrowing money, refinancing their homes, incurring credit card debt and using retirement savings.

Low-income Oregonians are largely covered by the Oregon Health Plan, which provides comprehensive health insurance at virtually no cost. But people who are above OHP’s income limits may face steep costs in buying insurance, as well as high deductibles.

The report also recommends the state “craft a strong accountability mechanism” to keep rate hikes in check with state target limits, and take action to lower prescription drug costs. The report states that while the state has implemented a Prescription Drug Price Transparency program that monitors price increases, there is little control over the market. It also calls for “efforts to minimize unnecessary consolidation in the health care industry,” which it says increases costs, limits access and can decrease the quality of care.

Guarino said OSPIRG is providing the report to lawmakers.

The most frequently listed debt holder was CareCredit, a credit card from Synchrony Bank used for out-of-pocket expenses. The report found that just over 1,000 debtors owed a total of more than $2 million to CareCredit, with the median amount owed higher than the median amount owed to the 10 most frequently mentioned health care systems. The report also notes that in 2013, the U.S. Consumer Finance Protection Bureau ordered CareCredit to refund more than $34 million to consumers for using deceptive enrollment tactics.

Among health care systems, the size of the provider generally aligned with its ranking: Filers owed Providence the most money, then Legacy Health, Salem Health Hospitals and Clinics, Kaiser Permanente, Samaritan Health, Oregon Health & Science University and Tuality, Asante Health, St. Charles and finally Catholic Health Initiatives.

Medical debt has increased in the years since the bankruptcies studied for this report were filed. Between the time the pandemic began and April of this year, 2.5 million more people than usual had medical debt enter collections, according to Credit Karma.

OSPIRG’s national chapter pointed to two factors contributing to more Americans being in medical debt: increased need for expensive treatment for people who contracted COVID-19 and job lay-offs resulting in the loss of income and health insurance.

“The report examined nearly $30 million in medical debt, and this is just the tip of the iceberg,” Guarino said. “Bankruptcy filings give us a unique window into the extent and severity of medical debt in Oregon, but it doesn't tell us everything. The report only represents some of the financial strain health care costs impose on Oregon households.”

Read the report: “Unhealthy Debt: Medical costs and bankruptcies in Oregon.”

You can reach Emily Green at [email protected] or on Twitter @GreenWrites.

The article while supporting what we know i.e. Medical Debt is creating 60% of the Bankruptcies does a disservice by only offering one solution. The report was done by OSPIRG. It is a good report and necessay information. However, it is obviously pushing OSPIRG's agenda. There is another way to skin this cat, a publicly financed system of health care. Oregon State passed SB770 which established the Task Force on Universal Health Care with the responsibility to deliver to the Oregon Legislature "How the State can implement a publicly financed system covering everyone in Oregon". The article claims that the public option would reduce the cost of medical care. I have not seen any proof of this. The problem with the public option is that it will become just a part of the market place. It cannot nor will it ever control the major reasons why the cost for health care keeps escalating. It will not control the 20% to 30% additional costs for administration, the costs of pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, nor the rising costs of hospital care and mergers. Public option is a red herring, just another band-aid on an open festering wound. As long as we keep health care in the market place, we treat human beings as consumers. However, people do not shop for the diseases or accidents they get, nor can they shop for the cure during a time when they are sick and facing medical hardships. Consumers are people that the market profits from. Human beings are people that need their healthcare need to be met.

Your article is appreciated, however it should have covered the larger picture.