Oregon has adopted a set of goals to reform health care, make Medicaid spending more efficient and improve the health of the one in four Oregonians covered by the insurance.

The Oregon Health Policy Board on Monday approved a report describing the state’s priorities, which include improving behavioral health care and shifting to a pay model that rewards boosting health instead of paying for individual procedures. They also include keeping health care costs down and investing in social determinants of health such as housing security.

The report is the first step in the application process for coordinated care organizations vying for the next five-year contract to manage the Oregon Health Plan, the state’s version of Medicaid. Patient care is managed by the organizations, which act as insurers and contract with providers.

While health professionals say they support the direction in which the state is moving, many said there’s a long road to get there. It first needs to fix the existing system, which remains disorganized and strapped for cash, they said.

Former Gov. John Kitzhaber -- who designed the Oregon Health Plan in the 1990s -- recently criticized the existing system, calling it “siloed” and “unaccountable.”

The state is also on track to increase Medicaid spending in 2019 by 4.2 percent, missing its goal of keeping cost increases to 3.4 percent or less.

Critics say the state needs to fix how it pays coordinated care organizations. The current model disincentivizes them from improving patients’ health, they said. The state’s newest proposals for addressing social determinants of health will further the financial burden on the organizations, said Josh Balloch, vice president of government affairs and health policy at AllCare Health, a coordinated care organization in southern Oregon.

The proposal also fails to set clear expectations or describe how the state will evaluate the progress of coordinated care organizations in managing their clients’ health, critics said.

“There’s a huge gap between what they want to get and where they’re at,” said Dr. Bob Dannenhoffer, a Roseburg pediatrician. “The goals are absolutely great, but the move from ‘these are our goals’ to ‘this is how we’re going to get there’ is totally unclear.”

Jeremy Vandehey, director of the health authority’s Health Policy and Analytics division, agreed that the Oregon Health Authority needs to set clear expectations for coordinated care organizations and providers.

"In order to make these improvements a reality for our members, our team at (the Oregon Health Authority) needs to hold ourselves accountable to monitor and enforce new and existing contracts with CCOs," Vandehey said in a statement.

Improving Behavioral Health Care

The report calls for increased access to behavioral health care by decreasing wait times, giving patients more choice on who they see and making the behavioral health system easier to navigate.

It makes coordinated care organizations “fully accountable” for ensuring an adequate provider network, timely access to services and effective treatment.

The Oregon Health Authority report says the agency will identify specific metrics to track coordinated care organizations’ progress toward improving behavioral health care. It says that the health authority will take corrective action if the organization fails to meet those metrics.

Devarshi Bajpai, Multnomah County’s mental health Medicaid manager, said solving the workforce issues requires paying behavioral health care providers who serve Medicaid patients more.

“It’s hard to retain people in the workforce,” he said.

Value-Based Pay Far Away

The report asks coordinated care organizations to make a “significant move” toward a payment model that would reward health outcomes and away from the current model that pays a fee for each procedure or service that a patient receives.

The “fee-for-service model” encourages providers to do more procedures to get paid more rather than doing what is in the best interest of the patients’ health.

Within the first year of the new contract, the state expects coordinated care organizations to spend 20 percent of the Medicaid dollars they receive on outcome driven, or “value-based,” payments to providers. By 2024, the report says 70 percent of all Medicaid payments to providers should be value-based.

The state report offers multiple ways that coordinated care organizations could pay based on health outcomes, several of which center around paying clinics a lump sum to care for a certain population or certain conditions and having providers practice care within those means.

One option penalizes providers by having them cover any costs that exceed the budget set by the coordinate care organization.

Another option mirrors the way the state pays coordinated care organizations.

Each year, the state pays them a certain amount per patient each month, based in large part on how many members the organization covers, how sick they are and how much the payer spent the previous year. The state then gives the organizations bonuses at the end of the year if they meet certain quality metrics such as child immunization status, depression screening, cancer screening and others.

Critics say that model doesn’t work.

Basing the monthly “capitation” rates on how healthy the patients are discourages organizations from making their populations healthier, said Josh Balloch, vice president of government affairs and health policy at AllCare. If the health of their patients improves one year, the coordinated care organization gets less money the following one because the risk of having to payout high health costs is lower.

Asking coordinated care organizations to spend money on social determinants of health will further discourage them financially, Balloch said. When payers invest in efforts outside clinics, like housing and community outreach programs, they are not able to bill Medicaid based on codes.

That means it will be hard to get reimbursed for those added costs, Balloch said. If the social determinants of health improve their patients’ overall health, they will also get lower rates the next year, he said.

“Until we can figure out a mechanism to fix this, you are double disincentivized,” Balloch said.

Improving Oversight

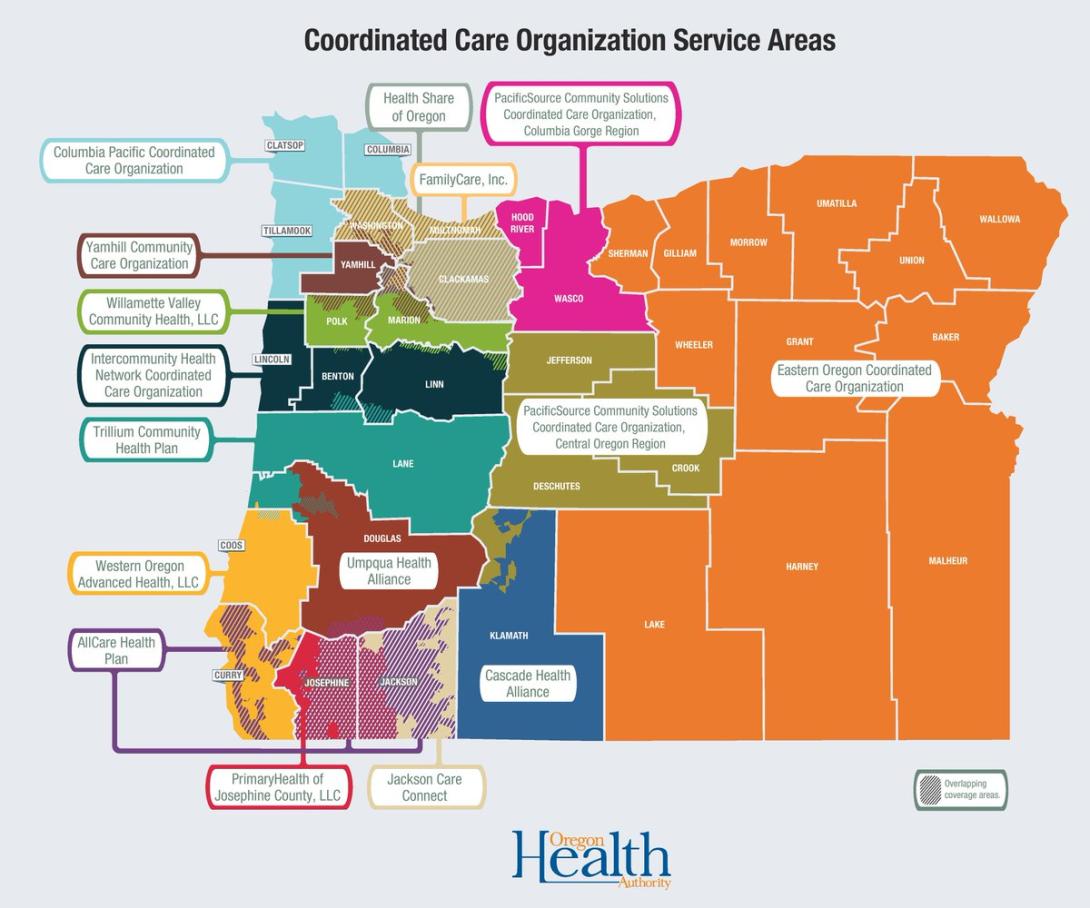

The state currently pays 15 coordinated care organizations to manage care of the nearly 1 million Oregonians on Medicaid, but their contracts end December 2019.

The state will release a request for applications based on the report in January, and organizations will apply in March for a contract to manage care from 2020 to 2025.

Several coordinated care officials told The Lund Report that they are waiting to see how the state turns these goals into application and contract language before they decide whether or not the goals are doable.

“The (request for applications) may be the most definitive statement for what is important for (coordinated care organizations) to drive as part of CCO 2.0,” said Lindsay Hopper, vice president of Medicaid programs at PacificSource, a coordinated care organization.

The report calls for the next round of contracts to clearly define expectations for coordinated care organizations.

“OHA also has a responsibility to conduct effective oversight of the program to ensure members across the state receive the care they deserve,” the report said.

Two things are essential as well as difficult:

Enough funding so good performance is rewarded sufficiently and not immediately penalized by lower rates next year; and enough risk structured properly (pain shared by all provider institutions and specialty groups), so that the fear of financial failure "focuses the mind wonderfully," as one's hanging date in two weeks is said to do. Without the reward, that kind of risk won't be accepted, and without the risk, little changes.

Premium funding must take into account keeping the rewards high enough. Experience says 5-10% for good results is what it takes to motivate physician groups to do this very hard work, and this is likely similar for other provider entities [read: hospitals] to be willing to reduce other revenue by fully participating in cost and quality management.)

Some increase in funding is almost certainly necessary to move off the dime on these needs, especially if the legitimate need to address factors like social determinants of health is to be addressed. OHA and the legislature must act to make this possible. Otherwise we continue to engage in magical thinking.