Oregon’s facing an $8 billion question: Can state bureaucrats and politicians reinvent the health insurance program that covers one in four Oregonians and push the entire state to get healthier along the way?

That figure is the size of the state’s annual Medicaid budget. Getting better results from those dollars – and keeping out-of-state investors from profiting from Oregon’s reforms – is at the heart of a yearlong effort to rewrite the program’s rules. The state’s choppy first attempt at Medicaid reform, launched in 2012, expanded access to medical care and held down some costs.

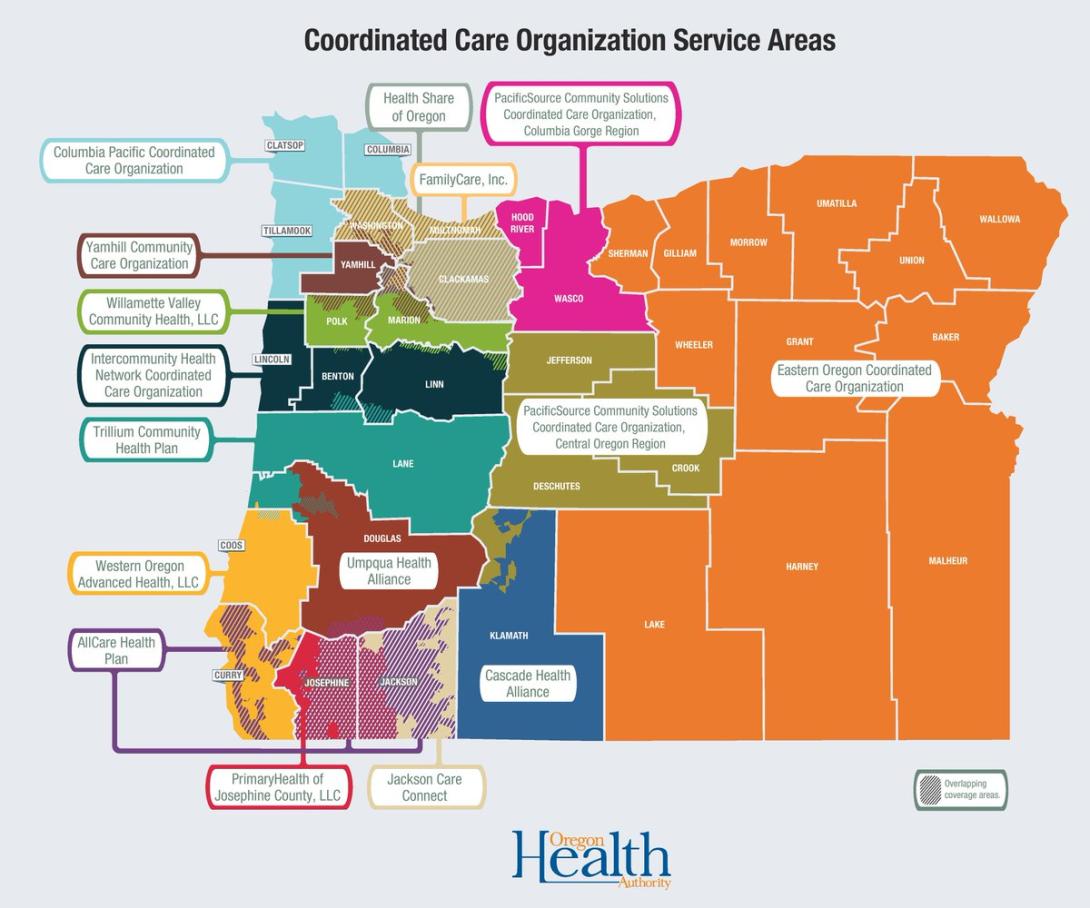

Round 1 stepped outside the box by introducing coordinated care organizations, or CCOs, which act as insurers to Medicaid enrollees. Oregon’s leaders say this system, which takes a community approach, with 15 care organizations across the state, is a model for the country. But studies show results here have been middle of the road. Oregon pays more than most states for the Medicaid services it buys and ranks near the bottom for getting at-risk patients to the doctor.

Even the state’s chief health care bureaucrat says the initial system did not go far enough.

Now, the Oregon Health Authority is working on Round 2. If thinking outside the box is not enough, officials may have to break it.

They’ve spent the last few months on a 2,000-mile road trip trying to crowdsource ideas from across the state, talking to Medicaid members, doctors, nurses, therapists, county commissioners and service providers in search of an elusive goal: spending less and yet improving the state’s health at the same time.

The state aims to have a rough plan in place by October, with rules going into effect in 2020. Officials agree that the Oregon Health Plan, which oversees Medicaid, needs a rehaul. They recognize that they need to think beyond the doctor’s office and pay for results -- not procedures. They also say that the health plan needs to do a better job of addressing mental health concerns, addiction and lifestyle issues, like homelessness, that affect health.

But the devil is in the details.

Beyond the Doctor’s Office

A big issue that policymakers are grappling with has to do with the “social determinants of health.” This is a complex brew that includes genetic makeup, the environment, personal choices and the influence of society.

“Only 10 percent of health is determined by what happens in a doctor’s office,” said Jeremy Vandehey, Oregon Health Authority director of health policy.

Yet nearly all of Oregon’s Medicaid spending is built around the medical care system. Figuring how to shift that focus is a big challenge.

When the health authority crisscrossed the state this spring and summer to talk to community members about their health wish lists, housing came up again and again. In the Portland area, discussions centered on caring for a large homeless population as tent villages proliferate in parks and on sidewalks. In rural areas, climbing rents and too few apartments are creating housing crises in communities that have never faced large-scale homelessness before.

“There’s actual evidence that shows when you provide a person housing, they are healthier,” said Coos Bay pediatrician Dr. Carla McKelvey, a member of the Oregon Health Policy Board.

It’s one thing to recognize the link between housing and health, yet another to figure out how to embed that link in Medicaid contracts. Should Medicaid funds be directed away from doctors and labs? Should coordinated care organizations build housing even though that’s outside their area of expertise? How much should each community-based coordinated care organization be allowed to experiment, and how much should be dictated by the state?

The Oregon Health Policy Board is ultimately responsible for writing the rules coordinated care organizations will have to follow under health reform Round 2. Board members agree that a statewide housing crisis is bad for the health of Medicaid members – but they don’t know what to do about it.

“Let’s take HealthShare, the state’s largest (coordinated care organization). It covers the metro area, which has one of the highest housing challenges,” said Felisa Hagins, political director of Service Employees International Union Local 49, and a board member. “If you said to them tomorrow, in five years 100 percent of your population needs to be housed, how would they get there?”

Paying for rent subsidies, for example, would take limited funds that might otherwise go to paying for medical treatment.

“We are not going to decrease administrative costs, have (coordinated care organizations) offer rent subsidies, and get the health outcomes we are looking for,” Hagins said. “I want to make sure that if we are setting a priority, we are holding people accountable for that priority.”

And housing is just one of a raft of these so-called social determinants of health. Limited access to transportation can affect a Medicaid member’s ability to see a doctor or to shop for healthy food. Cultural miscommunication can leave non-English speakers uncertain of what medical benefits they are able to receive.

Zeke Smith, chairman of the health policy board, said leaders are still trying to figure out how to build these community needs into the next round of Medicaid contracts.

“I don’t think our job is to say, ‘(coordinated care organizations), solve the problem,’” Smith said. “If we set statewide priorities, there’s an ability for each local community to articulate how to address them.”

Behavioral Health

During Round 1, coordinated care organizations have focused on paying for physical health concerns, while struggling to meet the needs of members with mental health challenges.

“There are wait lists. There’s a lack of access to providers. There are people not able to navigate the system,” said David Bangsberg, founding dean of the Public Health School jointly established by Portland State University and Oregon Health & Science University.

Around the state, Medicaid members say that not only are their options are lacking -- but also the process for getting help is complicated and often culturally insensitive. Some have complained that the therapists who speak Spanish do not understand Latino cultural norms. Others say too few mental health providers understand how to work with gay and transgender patients.

Leaders acknowledge the gaps but are grappling for solutions as they write the guidelines for Round 2.

“We want to make sure (coordinated care organization) members have the right care at the right time, when it comes to addiction and mental health care, without having to figure out how to navigate a complex system,” said Vandehey, the state’s director of health policy. “Sounds like a pretty simple goal, but we’ve been trying to improve behavioral health for a long time in this state, and we haven’t gotten there yet.”

Lowering Costs

Round 1 of Medicaid reform was built around metrics that were easy to identify and count.

Coordinated care organizations were instructed to track childhood immunizations and to follow up with patients who were screened for depression, for example. When they score well, they’re rewarded financially. This year, the Oregon Health Authority is paying $178.3 million to coordinated care organizations for meeting their goals.

The theory is that paying for results that are linked to better health leads to healthier people and lowers future costs.

It has worked, up to a point. Medicaid spending in Oregon has been held to 3.4 percent per member each year since 2012. That’s slightly less than the 3.6 percent per capita increase in Medicaid spending nationwide.

But policymakers want to tamp down costs even more.

Former Gov. John Kitzhaber, who was in instrumental when he was in office in crafting the first round of Medicaid reforms, doesn’t think the financial incentives are in place. He said Round 1 actually undermined the state’s goals.

Actuaries, financial specialists who determine costs, estimate how much medical care each Medicaid member is likely to need. Then, the Oregon Health Authority pays coordinated care groups accordingly -- with more money flowing to organizations that have sicker members. Each coordinated care organization can get a bonus of up to 4.25 percent for scoring well on the state’s report card.

Kitzhaber said these formulas reward medical providers for lab tests and procedures, with only a small incentive pool available to pay for better results.

“This is exactly what we were trying to avoid,” he said. He urges state policymakers to use Medicaid funds to pay for improving health, rather than medical procedures.

But the question is: How can Oregon achieve that goal?

Tina Edlund, Gov. Kate Brown’s director of health policy, notes that coordinated care organizations act as insurance companies, not medical providers. The state wants to reward doctors and nurses for providing better care -- but there’s no guarantee that coordinated care organizations will pay for results instead of procedures.

“It’s wonky health policy, but it’s key to driving down costs overall,” Edlund said. “We have to get payment aligned with where our goals are.”

Caveats and Criticisms

The effort to draft Medicaid Round 2 has champions and critics.

Mike Shirtcliff, founder of Redmond-based Advantage Dental, which serves 340,000 Medicaid members, said the next draft may get bogged down by administrative overhead and bureaucratic complexity. Kitzhaber worries that Oregon’s leaders won’t be able to overcome federal regulations and get a green light from a hostile Washington, D.C.

Round 1 involved a number of notable stumbles -- including the resignation of a health authority leader, failures with enrolling and re-enrolling Medicaid members that took years to correct and the collapse of FamilyCare, which had been the second-largest coordinated care organization. The insurer is still suing the state over reimbursements.

There have also been concerns about the purchase of Lane County’s Trillium, a nonprofit coordinated care organization considered fairly innovative, by Centene Corp. for $100 million. The California company, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, specializes in making money off of Medicaid for its shareholders.

Oregon’s results, too, have been somewhat mediocre compared with the rest of the country, according to research groups.

Pew Trusts, for example, has pointed out that 12 percent of state budget went to Medicaid in 2017, putting Oregon slightly ahead of the national average, ranking 14 among the states.

Kaiser Family Foundation found that Oregon’s Medicaid programs paid about 11 percent more than the national average to physicians in 2016; with the 18th highest payments per medical visit.

And an analysis by the Wallet Hub financial website that used federal data ranked Oregon 35th out of the 50 states and Washington, D.C.-- with higher costs than the country’s average, but also better health results.

The Road Ahead

Though much needs to be changed in Oregon Medicaid system, officials aren’t planning to wipe the slate clean.

“Hopefully (the first round) is not about starting over,” said Eric Hunter, chief executive of CareOregon, a nonprofit that provides services for a number of coordinated care groups.

“There has been incredible success and innovation with (the first round). Hopefully, we can build on what we’ve got,” he said.

Experts worry though that policymakers will just add on to the current system, rather than reworking the core, which could create a hodgepodge of rules and guidelines that don’t accomplish the overall goals.

There’s also the question of getting approval from the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, which must agree to the way Oregon spends federal dollars.

“None of us can predict what will happen at the federal level, said Tina Edlund, the governor’s chief health care adviser. “Will those proposals go anywhere? We don’t know.”

Officials would like to reform the entire health care system, which is considered broken. Americans pay far too much for what they get compared with other industrialized nations.

But that would require a larger collaboration, said Edlund.

In addition to roughly 1 million people covered by the Oregon Health Plan, two state-run health insurance programs cover about 300,000 teachers and public sector workers. Officials who oversee that system are not involved in the discussions.

Policymakers hope to have more concrete proposals ready by August, and a draft by October. Then the state’s 15 coordinated care organizations will be invited to submit their plans to take Medicaid to Round 2 -- and other health-care groups will get to bid to join the system, too. The new Medicaid contracts that will start in 2020 will be shaped by the choices made in the weeks ahead.

Officials are determined to get this done.

“We don’t have the luxury of saying, ‘It’s too complex, let’s kick it down the road,’” said Zeke Smith, chair of Oregon health policy board.

Comments

CCOs and reform

I must disagree with the earlier comment that it is the insurance companies that are causing the inflation and inefficiencies. In my view, the providers - hospitals, ambulatory service centers, medical device makers/sellers, doctor's offices, clinics all contribute to the cost problem. Consumers also contribute to the problem. But our political discourse has a tendency to look for one villain. In my view in health care there are almost no "black hats" and "white hats" but many with hats of varying shades of grey. That in itself is the challenge - it feels like we are squeezing on a balloon but don't want the balloon to burst. I wish there was an easy and obvious answer - but there isn't one (at least that is possible). So I do not envy my friends in Oregon who at least are doing more than nearly any other state to at least try to find an answer or answers.

Where to start?

CCO's were formed to "transform" medical care -- but suddenly they have become the problem.

They were formed with the expectation that going forward, there would be "transparency" in medical financing -- but now it is more opaque than ever.

"Single payer" is the answer for a certain group -- but if it were run by the government, it would look like the VA or the British NHS, both destroyed by politics, and if it were run privately (say by UnitedHealthCare) it would look like Leland Stanford running the railroads.

The "old" system -- most routine medical care provided by GP's in private offices, with hospital care run by groups like churches, Elks, Shriners and county governments somehow doesn't look so bad in retrospect. The principal beneficiary of the present system is a parasitic caste of financial and administrative types -- not patients, doctors, scientists, teachers or public health in general.

Too-small incentives don't work

We rarely if ever see comments that draw from the small but crucial success story of HMOs working with PacifiCare in the Portland/Salem area more than 20 years ago. A number of medical groups sharing risk with PacifiCare, some with hospitals sharing also, had remarkably good results for both health care and cost management. In the successful years there was something like a 10% end of year risk reward for those managing well. As the baseline of costs (mostly hospital costs in length of stay and admissions avoided) decreased with success, and premiums came down to match, the incentive steadily eroded until it became just a few percent or less. The hard work of managing care done by PCP groups became not worth the time and effort for any but the few with the greatest passion for it, and they were too few to sustain that system. Those I knew said the incentive just didn't warrant the extra hours and effort it takes to do such close management.

Now, it will take budgeted dollars that aren't vulnerable to premium decreases, to create an incentive pool that will reward adequately. If you talk with those experienced in the work from that time (we aren't all dead yet), you will learn that anything less than 5% is not worth a long conversation, and closer to 10% is needed if one wants the reward. There is no reason the system should expect to freeload on the work of physicians or hospitals who actually manage costs, limiting their own revenue in the process.

If we don't want to fund that kind of system using private enterprise, Medicare for all is about the only robust policy solution there is to create access to covered care. Yes, price control is too much of how it contains costs, but it makes up in lower overhead for a large part of what it fails to do to manage in a better way.

Dancing in between these concepts isn't working, and won't in the future.

Your thoughtful comment

Thank you so much for being a member and for sharing your thoughtful insights. Feel free to always reach out to me directly at [email protected]

Thank you for a good article. The CCO's are acting like insurance companies but nobody is delineating exactly how or why this is happening. If we put everyone in the same pool with publicly provided health care delivered privately, we would be able to cover everybody better for less money. The State would slow down medical inflation by bargain costs of services, medical equipment, and drugs. 1 M people on Medicaid, 750,000 people on Medicare, 300,000 public employees, if we could get those dollars we could probably cover the rest of the population with a some tax dollars. It is the insurance companies that are causing the inflation and inefficiencies