The surge in patients at the Oregon State Hospital is being driven almost entirely by patients from Multnomah County who have been arrested but need to be mentally stabilized before they can stand trial.

More than a third of those patients are being confined after allegedly committing petty misdemeanors.

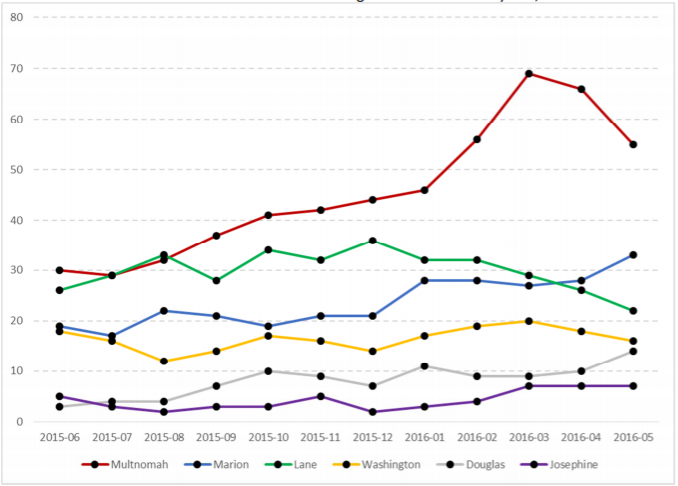

The Lund Report retrieved data from the state mental hospital that shows the patient count of “aid & assist” patients from Multnomah County surged from 30 in June 2015 to 70 such patients nine months later (March 2016), as the overall population grew from about 160 to about 200.

The number of Multnomah County patients has since declined to about 53, but only one other county has shown a significant growth in -- Marion, which includes Salem. But 76 percent of these patients from Marion County those are accused of felonies, the group where the state hospital is often the only place equipped to treat them.

From 2002 to 2011, the number of people at the state hospital awaiting trial hovered consistently between 67 and 88, but since then, the population has grown by leaps and bounds, to 114 in 2012 to 150 in 2014, 190 in September 2015 and 210 as of April 2016.

The growth of patients who have been charged but not convicted of a crime have been exponential, most of the state has not contributed to this problem. “This is not a statewide issue,” Greg Roberts, the superintendent of the Oregon State Hospital, told The Lund Report.

Capt. Steve Alexander, the public information officer for the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office, was unable to respond by press time to explain about what may have changed at his county to explain the uptick in people with mental illnesses sent to the state hospital while they await trial.

Roberts explained that often police officers believe they’re doing the right thing by piping mentally ill people to Salem, but in reality, these patients in this class are only stabilized to the point that they can appear in court to “aid and assist their attorney in their defense,” and are not offered the step-down plan of other patients.

“The police actually believe they’re helping the person,” Roberts said. “The person needs help, but they’re not committable. The only way to get them into treatment is to arrest them.”

Hospital Unable to Treat Others

The situation is putting the state’s capacity to serve mentally ill people in its two institutions to the brink, forcing open a new wing for aid & assist clients at the central hospital in Salem and nudging the state to open a new treatment corridor at the auxiliary hospital in Junction City. Meanwhile, the Salem hospital has less room for people who’ve been civilly committed.

“The wait list for civil patients has significantly increased,” Roberts said, leaving many of these patients stuck at local hospital emergency rooms and psychiatric wards and in need of more intensive care. Patients can be civilly committed when they are a violent threat to themselves or others.

Because of the acute nature of “aid & assist” patients’ mental illness, they can only be treated in Salem, not Junction City. “[These] patients are the most expensive because of all the evaluation we do,” Roberts said.

State law also requires that the aid & assist patients, along with patients who’ve been found guilty except for insanity be treated before other patients not accused of committing a crime.

When the Salem was opened in the last decade, planners projected the “aid & assist” population would remain stable, while the “guilty except for insanity” group would grow. Instead, that population has declined, which has allowed the hospital to take on more “aid & assist” patients and has kept the problem from becoming worse, Roberts said.

State to Triage Problem Counties

Last month, Oregon Health Authority Director Lynne Saxton announced that the state would be working with the six counties with high numbers of patients to reduce their numbers. They include Multnomah, Washington, Marion, Lane, Douglas and Josephine.

Lane and Washington have sent larger than average numbers of people accused of misdemeanors to the state hospital, while Washington County’s overall numbers are low for its size, but 42 percent had only been accused of petty crimes. Little Coos County had seven patients at the state hospital, and only two had been accused of felonies.

More than three-quarters of the patients from Douglas and Marion counties, on the other hand, were accused of major crimes before they were sent to the hospital.

Marion County has been touted as the model for counties and police agencies for handling people with mental illness in crisis. The state has funded crisis intervention teams at the Marion County Sheriff and Salem Police departments the past few years, and the Legislature recently funded an expansion of that model to Klamath County.

Rep. Mitch Greenlick, D-Portland, the chairman of the Oregon House Health Committee, told The Lund Report he hoped the counties would stop arresting mentally ill people on misdemeanors, and suggested the counties may be passing off their problems onto the state so that they don’t have to deal with them in their jails or psychiatric treatment centers.

Greenlick Floats Charging Counties

Greenlick said if the counties do not get this problem under control, he would support legislation requiring them to pay for the people they send to the Oregon State Hospital.

Mobile crisis teams that allow law enforcement agencies to avoid sending mentally ill people to jail or the state mental hospital appear to be the best immediate response to the surface problem, but of course, at its root, the crisis grows out of a failing community mental health system in Oregon, where a lack of coordination and inconsistent funding have prevented local agencies from appropriately treating people with mental illness before they’re forced onto law enforcement.

Fortunately, “The Legislature has approved a lot of money to support community health programs and supported housing,” Roberts said. “We’re on the right path it will just take time to develop these programs.”

He said if these programs can be sustained and promoted, it will become unnecessary for many of his patients to come to the state institution.

But it’s going to take more than just throwing money at the problem for Oregon to get results. The Affordable Care Act has also supplied federal funding to pay for the medical care of people in poverty, including mental health. And the coordinated care model was supposed to help the state’s Medicaid managed care organizations to treat mental disorders right along with other physical ailments.

But some of the CCOs have made little progress, and the quality control metrics that ensure the CCOs are adequately treating mental health and not just dodging this issue are lacking. For the new Medicaid waiver before the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Reform, Saxton and Medicaid Director Lori Coyner plan to ask for more federal investment in the CCOs to help with mental health coordination.

To see more of the data click here.

Re Mitch Greenlick's suggestions that the counties start paying for the people they are arresting and sending to the state hospital, so they can receive treatment and help, is worrisome. My concern here is that the community supports being touted to prevent these situations are not in place. It will take years to fix the broken mental health system. These people who the police are trying to help may once again languish in our jails and prisons, instead of getting the treatment and care they need. The counties already have space for them in their jails and prisons, no need to start paying more to send them to the hospital, this scenario is a real possibility. Also, as the article points out, there is no step down plan for the people who are "fit to proceed" -- why isn't there? I would guess that these poor souls once again become part of the enternal revolving door. It is apparent that more hospital beds are needed to ensure that all who suffer from severe mental illness have a bed and treatment. Hopefully the state is not considering placing those who suffer so in the jails and prisons because of lack of beds. Mental illness is not a crime.

Mary Murphy