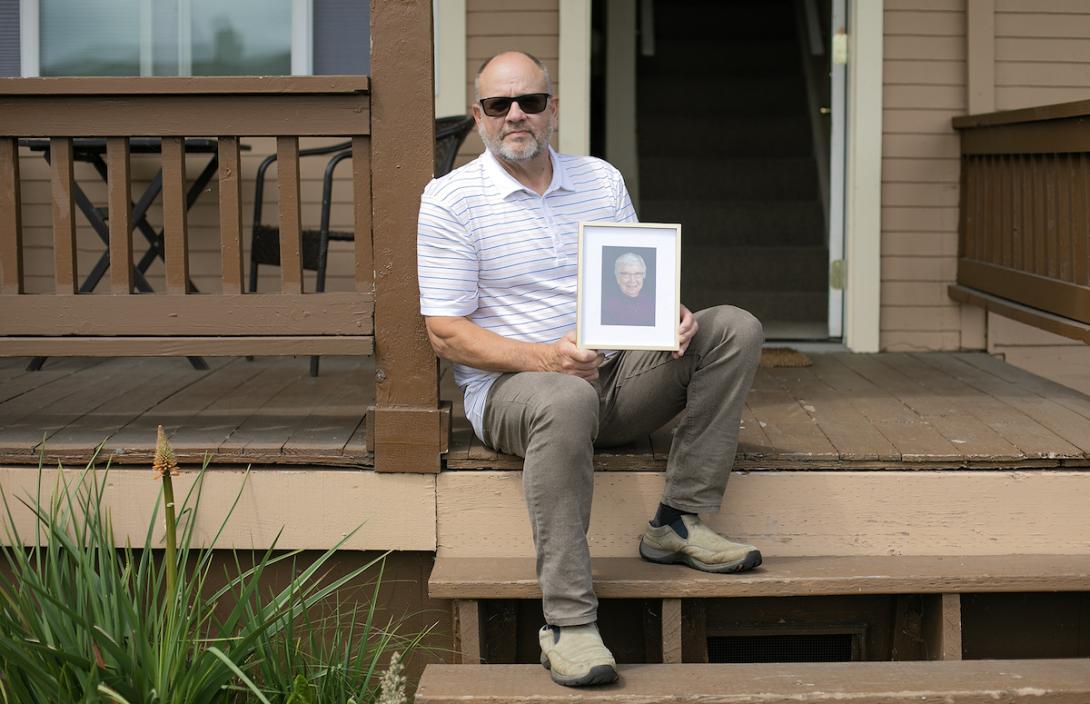

EVERETT, Wash. — John Stejer wishes his mom, Betty, still lived close enough to visit at least weekly. Instead, when her memory and judgment diminished rapidly, the only place he could find an affordable assisted living bed was in Tucson, Arizona.

“We all thought this is where she would spend her last days with family,” Stejer said. “To discover that there was no place in the state — I mean, no place — that was really discouraging. And I was actually in disbelief.”

Stejer has lived in the Everett area for nearly 40 years, now in a small, two-bedroom home with one bathroom and stairs. He is currently raising his grandson there. In 2021, his then 86-year-old mom was living independently in an apartment in Marysville, with neighbors who looked out for each other.

But she had wandering episodes close together in October. In the first one, she just ran out of gas — which was unusual. The second time, she spent the night disoriented and outside in very cold weather, after she had driven to the end of a remote logging road in Darrington. A hiker found her the next afternoon and alerted police. Stejer had filed a missing person’s report in the morning.

After a short hospital stay to recover, her doctor strongly recommended assisted living and memory care because she was no longer safe alone. So Stejer, who was retired, started on his crash course of options for her. His only other sibling, a brother, lives in Australia.

As Stejer searched, he hired a family friend to provide home care for his mom four days per week. She was forgetting to eat, and he worried that she would forget her medications. Meanwhile, he also stopped by to check on her almost every day. And he took away her car.

With Social Security income, a small pension and $12,000 in the bank, Betty Stejer would be eligible for Medicaid to pay for assisted living after about one month of spending a lot of her savings. She did not want to live in an adult family home.

Stejer said he called 17 facilities. Some had waiting lists so long that they weren’t even taking names. His mom’s name is still on one list. He felt “bewildered and overwhelmed,” as he tried to find good information and credible sources, while figuring out the best, safest care for her that they could afford.

“I knew I was getting unhelpful answers from people that said they were there to help me, but were really not. They were there to enrich themselves. I was afraid to ask questions, because I was afraid I was going to get steered the wrong direction,” Stejer said.

He understands these facilities and other services need to “make a buck.” But he learned the hard way that as nice and well meaning as some seemed up front, “When they found out that my mother didn’t have the assets to pay for their facility, then they told me right away, ‘Well, we can’t help you.’”

Stejer could not find a Medicaid-assisted living bed anywhere in Washington, or at least not without two years of “spend down” cash, which no one in the family could afford. Spend down refers to a facility asking for the full rate for several years, which can be significantly higher than the Medicaid rate.

Around Snohomish County, two to four years of spend down is common, according to industry experts and Homage’s directory. Patients can pay with their social security, pensions or the sale of assets.

Medicaid funding falls short

Assisted living facilities are not required to reserve any beds for Medicaid clients. They determine what to do based on their overall mix of funding and finances. And the funding for Medicaid assisted living beds has not kept up with operating costs, leading some to close those beds, according to industry representatives and several operators.

At Josephine Caring Community in Stanwood, chief executive officer Terry Robertson said they reserve about 30% of their assisted living beds for Medicaid payers.

“If we went more than that, we couldn’t break even and we couldn’t make payroll,” Robertson said. He blamed low reimbursement rates and regulations, relative to the other states he has worked in during his nearly 40-year career. He has also increased wages to recruit and retain staff during the current workforce shortage.

Josephine Caring Community is a nonprofit offering multiple types of long-term living, care and rehabilitation options, as well as a child care facility. Robertson estimates the average full payment for an assisted living patient is $7,000 per month, compared to the average Medicaid payment of $3,300 per month. Those numbers factor in a range of add-ons like a private shower, extra medication management and more.

When asked about spend down, Robertson said they require it “because we have to have a profit for at least a couple of years, to subsidize the Medicaid underfunding.”

The funding is complicated. At a basic level, the Medicaid rate pays a percentage of estimated labor costs and, separately, a percentage of estimated operating costs. Washington has been paying 68% of the estimated costs.

During the 2023 state legislative session, the industry asked for a budget that would fund 100% of labor costs in this funding formula. The final budget funds labor at 79% and operating costs at 68%. The state Department of Social and Health Services will also update the labor rates in fiscal year 2025, using the latest data that will reflect wage inflation.

The budget also funds add-ons for specialized dementia care and for facilities with at least 90% Medicaid patients.

$22,000 later

Robertson said he’s thankful to legislators for approving an increase, but facilities need more. Alyssa Odegaard, vice president of public policy at LeadingAge Washington, said that’s what she’s hearing from their assisted living member facilities.

“I don’t think that this level of funding is going to incentivize more providers to take Medicaid. It will prevent some, potentially, from closing doors. But we’re still really far off from where we need to incentivize growth in the program,” Odegaard said. “And then competing for attracting workers in the workforce. Assisted living direct care workers get paid pretty much the lowest in all of the long-term care settings.”

Bea Rector, assistant secretary of Washington’s Aging and Long-Term Support Administration, said the Legislature has been trying to make investments to ensure assisted living remains an option for Medicaid-eligible patients. Special rate add-ons are part of that effort. In the big picture, the administration wants to help people stay in their home when preferred, with services, as well as fund facilities at a rate that ensures a stable direct care workforce.

“In Washington, we’ve got an entitlement to home and community-based services, which is not true in every state,” Rector said. “And we want to maintain that entitlement without needing to create waitlists or reduce services as the caseload doubles, which is what we’re expecting over the next 20 years.”

Rector also mentioned the new WA Cares fund, which will add a payroll tax to help many workers pay for up to $36,500 in long-term care starting in 2026. The state will adjust the benefit annually for inflation.

Stejer finally broadened his search through A Place For Mom, a national memory care facility broker offering free referral services. After a few months, he found an assisted living facility that would take her and provide memory care. In March 2022, Stejer moved his mom to Tucson.

To make it work, he used up her $12,000 in savings, maxed out her credit card, and used his own credit card to pay four months of spend down, or about $22,000 in total.

Now he tries to visit every two months, sometimes flying, sometimes driving. He’s getting to know the Nevada, Utah and California routes quite well, and where the gas is cheapest. He also helps her to get her hair and nails done — one thing that the facility doesn’t provide. His daughter tries to make the trip from Washington at least once per year.

Stejer and other family members talk to her on a GrandPad tablet where they can also play checkers. He said she’s comfortable there, but more than a year later, it still feels a bit raw for Stejer. At some points, as he navigated hurdles, he felt close to a meltdown.

“The bottom line,” he said, “is that a Washington resident had to move out of state to receive affordable memory care. And that is disgraceful.”

Resources

Homage’s Aging and Disability Resource Network can provide free consultation for people seeking to understand their long-term care options: 800-422-2024 or homage.org/aging-and-disability-resource-network/

The state Department of Social and Health Services offers search tools and complaint information for different types of long-term care: dshs.wa.gov/altsa/residential-care-services/long-term-care-residential-options