In 2013, about 40 million family caregivers in the United States provided an estimated 37 billion hours of care to an adult with limitations in daily activities. The estimated economic value of their unpaid contributions was approximately $470 billion in 2013, up from an estimated $450 billion in 2009.

INTRODUCTION

Providing care for a family member, partner, or friend with a chronic, disabling, or serious health condition—known as “family caregiving”—is nearly universal today. It affects most people at some point in their lives. The need to support family caregivers will grow as our population ages, more people of all ages live with disabilities, and the complexity of care tasks increases. Without family-provided help, the economic cost to the U.S. health and long- term services and supports (LTSS) systems would skyrocket.

The contributions of this invisible workforce often go unnoticed. Part of the Valuing the Invaluable series on the economic value of family caregiving, this report recognizes the crucial services of those who provide unpaid care and support. It uses the most current data available to update national and individual state estimates of the economic value of family care.

In 2013, about 40 million family caregivers in the United States provided an estimated 37 billion hours of care to an adult with limitations in daily activities. The estimated economic value of their unpaid contributions was approximately $470 billion in 2013, up from an estimated $450 billion in 2009.

This report also explains the key challenges facing family caregivers. Marta’s story (see page 2) illustrates the intricacy of family caregiving today. The report highlights the growing importance of family caregiving on the public policy agenda. It lists key policy developments for family caregivers since the last Valuing the Invaluable report was released in 2011. Finally, the report recommends ways to better recognize and explicitly support caregiving families through public policies, private sector initiatives, and research.

One Caregiver’s Story

Marta, age 53, is married and the mother of two children in college away from home. She also works at a demanding, full-time job as an information technology specialist. Following the death of her father 2 years ago, she moved her 89-year-old mother into her home. Marta grew up knowing that one day she would care for her parents as she watched them care for their parents. Marta is the oldest of four children, but shoulders the majority of the responsibility for caring for her mom. Her three siblings live across the country.

Marta’s mother was diagnosed with vascular dementia 5 years ago. With disease progression, she has become more agitated, incontinent, and physically dependent. She also suffers from diabetes, hypertension, and macular degeneration. These multiple, complex chronic conditions contribute to her increasing frailty and need for greater assistance with everyday tasks.

While she would never admit it to anyone—even her husband and kids—Marta is exhausted. Between her mother’s two hospitalizations last year, all of her mother’s doctor appointments, handling bills and insurance, helping her mother bathe and dress, preparing food for special diets, and running home at lunch time to give her mother eyedrops and other medications, Marta always feels stressed. Even though she loves her work and has some job flexibility, Marta may have to cut back her work hours to a part-time schedule to provide more care for her mother. Such a change would be economically harmful to both Marta and her family—but neither she nor her mother can afford to hire in-home paid help. If she does cut back her work hours, Marta will lose her job-based health insurance, and take a huge hit on her retirement savings contributions. And, she will no longer be able to contribute to her children’s college tuition and living expenses.

Marta has started looking into options that would give her help in providing the much needed additional care to her mother at home. One of her greatest challenges is finding and obtaining affordable services for her mom who only speaks Spanish. While there are programs available, they are not located in her community, including several adult day centers. Transportation to and from appointments is already difficult. She cannot imagine having to do anything extra.

Marta often tears up thinking of how much she loves her family. She would do anything for them and she tries not to drop any balls. However, she is increasingly depressed and anxious, and worried about her and her own family’s future financial security. She recently went to see her doctor for back pain, but the doctor did not ask about her own living situation, her increasing strain, or how she was doing overall. She just does not know how much longer she can carry on like this. There is a caregiver support group at her church but she is uncomfortable sharing her story. She is concerned that people will think she is complaining. Marta feels alone and does not know where to turn.

UPDATING THE NATIONAL ESTIMATED ECONOMIC VALUE OF FAMILY CAREGIVING

This report estimates the economic value of family caregiving at $470 billion in 2013, based on about 40 million caregivers providing an average of 18 hours of care per week to care recipients, at an average value of $12.51 per hour.

These estimates are based on a meta-analysis of 11 surveys of family caregivers between 2009 and 2014, adjusted to a common definition: caregiver age 18+; care recipient age 18+; and providing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) (such as bathing or dressing) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (such as managing finances or preparing meals), currently or within the last month. For a discussion of data sources and methodology see appendix A, page 16. For estimates of the number of family caregivers and economic value at the state level, see table B1, page 19.

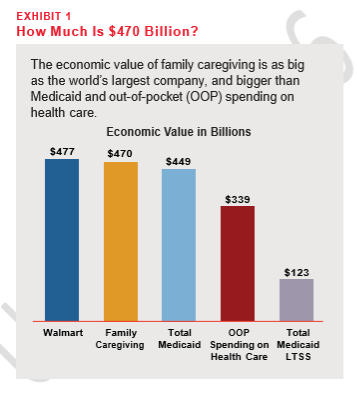

Some benchmarks can help to put this figure in more meaningful context. The estimated $470 billion is:

• More than total Medicaid spending in 2013, including both federal and state contributions for both health care and LTSS ($449 billion)1

• Nearly four times Medicaid LTSS spending in 2013 ($123 billion)2

• More than total out-of-pocket spending on health care in 2013 ($339 billion)3

• As much as sales of the world’s largest company (Walmart: $476.6 billion in 2013–2014)4

• As much as sales of the four largest U.S. technology companies combined (Apple, IBM, in the economic value of family care. Since the Hewlett Packard, and Microsoft: $469 billion in 2013–2014)5

• About $1,500 for every person in the United States (316 million people in 2013)6

PREVIOUS ESTIMATES OF THE ECONOMIC VALUE OF FAMILY CAREGIVING

The estimate of about $470 billion in economic value is consistent with prior studies, all of which found that the value of unpaid family care for adults with limitations in daily activities vastly exceeds the value of paid home care. Previous reports in the Valuing the Invaluable series have estimated the value at $450 billion in 2009, $375 billion in 2007, and $350 billion in 2006. 7

Other earlier estimates also showed steady growth in the economic value of family care 8 Since the last Valuing the Invaluable report, several other estimates include $199 billion (2009), $234 billion (2011), and $522 billion (2011–2012).9 These estimates differ from our $470 billion estimate due to methodological and definitional differences rather than contradictory data.10

Key Terms

Family Caregiver Broadly defined, refers to any relative, partner, friend, or neighbor who has a significant personal relationship with, and who provides a broad range of assistance for, an older person or an adult with a chronic, disabling, or serious health condition.

Caregiving Providing a wide array of help to an older person or other adult with a chronic, disabling, or serious health condition. Such assistance can include help with personal care and daily activities (such as bathing, dressing, paying bills, handling insurance claims, preparing meals, or providing transportation); carrying out medical/nursing tasks (such as complex medication management tube feedings, or wound care); locating, arranging, and coordinating services and supports; hiring and supervising direct care workers (such as home care aides); serving as “advocate” for the care recipient during medical appointments or hospitalizations; communicating with health and social service providers; and implementing care plans.

Intensive Caregiving Providing 21 or more hours of care per week.1

Long-Term Services and Supports (also referred to as“long-term care”)

The broad range of day-to-day help needed by people with longer-term illnesses, disabilities, frailty, or other extended health conditions. This can include: help with housekeeping, transportation, paying bills, meals, personal care, care provided in the home by a nurse or other paid health professional, adult day services, and other ongoing social and health care services outside the home. Long-term services and supports also include supportive services provided to family members and other unpaid caregivers.

Caregiver Assessment

A systematic process of gathering information about a caregiving situation to identify the specific problems, needs, strengths, and resources of the family caregiver, as well as the caregiver’s ability to contribute to the needs of the care recipient.2,3 A family caregiver assessment asks questions of the family caregiver. It does not ask questions of the care recipient about the family caregiver.4

Paid Sick Days (also referred to as "earned sick days") Generally a limited number of paid days off a year (typically between 3 and 9 days) to allow workers to stay home when they are sick with short-term illnesses, such as the flu. It also means limited paid days off a year to care for sick family members, or to accompany a family member to a medical appointment.5

Family Leave Longer-term time off to care for either new children or ill family members.6

Discrimination

Discrimination against workers caring for children, older adults, or ill or disabled family members. It arises from treating employees with caregiving responsibilities less favorably than other employees due to unexamined assumptions that their family obligations may mean they are not committed to their jobs.7

KEY CHALLENGES THAT FAMILY CAREGIVERS FACE11

Family members have always been the mainstay for providing care to aging and other relatives or friends who need assistance with everyday living. Yet family caregiving today is more complex, costly, stressful, and demanding than at any time in human history. Experts suggest that the family’s capacity to carry out its traditional functions is becoming strained due to the pace of social, health, and economic change.12

Family members and close friends often undertake caregiving willingly. Although many find it an enriching experience and a source of deep satisfaction and meaning, millions of people who take on this unpaid caregiving role, like Marta (see page 2), have no idea what to do, how to do it, or where to get help. These family caregivers are vulnerable themselves.

One study found that nearly 9 in 10 (88 percent) middle-income people in midlife said family caregiving was harder than they anticipated, necessitating more emotional strength, patience, and time than expected.13 In a recent national study examining the role and experiences of family caregivers of older adults, those family caregivers who experienced negative consequences reported that the most frequent negative impacts on their lives were exhaustion, too much to do, and too little time for themselves.14 These negative impacts were most common among family caregivers providing a high intensity of care, those who were caring for someone with dementia, and those who had health problems themselves.

Some experts have described family caregivers as an “invisible, isolated army” carrying out increasingly complicated tasks and experiencing challenges and frustrations without adequate recognition, support, or guidance, and at great personal cost.15 Despite the extent of their involvement in everyday care, family caregivers are often ignored by payers and providers—with no assessment of their own needs, capabilities, and well-being—or an acknowledgment of the interdependence of their situation and that of the person receiving care (care recipient).16

Research on family caregiving over the past 35 years shows that family caregivers can experience negative effects on their own financial situation, retirement security, physical and emotional health, social networks, careers, and ability to keep the care recipient at home. The impact is especially severe for family caregivers of individuals who have complex health conditions and both functional and cognitive impairments.17

Family Care Is Expanding and Increasingly Complex There is growing awareness that many family caregivers do much more than assist older people and adults with disabilities to carry out ADLs. Family caregivers traditionally have helped with tasks like bathing and dressing, shopping and meal preparation, transportation, and financial management.18,19 Many family caregivers today also help the care recipient to locate, arrange, and coordinate health care and supportive services, and to hire and supervise direct care workers when they can afford to hire help.

The landmark Home Alone survey, which explored in detail the extent to which family caregivers perform numerous medical/nursing tasks, found that almost half (46 percent) provided a range of these complex care activities in addition to helping with dailyactivities.20,21 Such medical/nursing tasks include wound care, managing medications, giving injections and tube feedings, monitoring blood sugar, preparing special diets, and operating medical equipment, among others. These medical/nursing tasks—once provided only in hospitals and nursing homes, and by health care professionals—are now being performed by family with little preparation or support.

Two out of three family caregivers who perform these medical/nursing tasks reported having no home visits for their chronically ill family members by any health care professional in the past year. Almost half were administering five to nine prescription medications a day, including administering intravenous fluids and injections. Forty percent of these caregivers expressed considerable stress and worry about making a mistake when doing these tasks. One-third said their own health was fair to poor.22

Family caregivers also serve as “advocates” for their family member during medical appointments, hospitalizations, or when the care recipient lives in other care settings, such as assisted living facilities or nursing homes. They facilitate communication and health care decisions with providers, especially during transitions of care. Family members who serve as decision makers for hospitalized older adults face a range of complex decisions about medical care, hospital discharge, and available and affordable supportive services. One recent survey found that family members (primarily adult daughters) were involved in decision making for nearly half (47 percent) of hospitalized older adults age 65 and older.23 But at the hospital, family caregivers are commonly considered “visitors” or an “afterthought” rather than crucial participants in their care recipient’s care.24,25

One recent study found that because of the bewildering complexity and fragmentation of our health care and LTSS systems, family caregivers who provide help with managing their older relatives’ finances experience the most difficulty in reviewing, explaining, and giving advice to their care recipient on health insurance, including Medicare and Medicaid. These family caregivers said that more information and simpler, easier to understand language would be helpful.26

Impact of Caregiving on Work

The majority of family caregivers (60 percent) caring for adults in 2014 were employed either full time or part time, placing competing demands on the caregivers’ time. Of those working caregivers, 4 in 10 (40 percent) were ages 50 and older.27 Older workers—especially older women28 who are most likely to have eldercare responsibilities—are an increasing proportion of the workforce.29 Because women are more likely to be in the workplace today than in the past, their earnings have become increasingly important for their families’ financial stability, retirement, and to the economy.30,31 One recent analysis finds that more than 8 in 10 (83 percent) people in their peak working years (ages 51–54 years) are at risk of taking care of their parents or parents-in-law with LTSS needs. For those nearing retirement (ages 60–69 years), more than 4 in 10 (45 percent) face a risk of providing parent care.32

A recent national survey of workers age 25 and older found that nearly 1 in 4 American workers (23 percent) say they are currently providing unpaid care to a relative or friend, most commonly for a parent or parent-in-law (53 percent). Among these workers, more than 1 in 5 (22 percent) say they provide about 21 hours a week or more of unpaid care in addition to holding down a paying job.33

When the stresses of juggling caregiving activities with work and other family responsibilities becomes too great, or if work demands conflict with caregiving tasks, some working caregivers make changes in their work life, especially if they cannot afford to pay for outside help.34 Workers who provide intensive caregiving (defined as 21 or more hours of care per week) are more likely to report an impact on their work situation, such as retiring early or quitting a job to give care due to the inability to afford paid help for their care recipient.35

Research suggests that family caregiving may reduce the likelihood of working.36 According to the 2015 retirement confidence survey, more than 1 in 5 (22 percent) retirees left the workforce earlier than planned to care for an ill spouse or other family member.37 Other evidence suggests that nearly one- third of working women who also provide intensive caregiving increase their odds of retiring earlier than planned due to their caregiving responsibilities.38

A national study of unemployed people ages 45 to 70 at some point during the past 5 years found that 26 percent of survey respondents were caring for a family member or friend during their period of unemployment. Forty percent of those unemployed family caregivers said family care affected their ability to look for or accept a job. Twenty-five percent of survey respondents waited to begin their job search because of their caregiving responsibilities.39

Access to unemployment insurance (UI) benefits can be an important safety net when family caregivers who had to quit their jobs begin searching for a new job. Many working caregivers assume they are ineligible for UI when they quit their jobs, and few are aware that half of states allow benefits for separation from work due to family circumstances, including the need to care for a family member experiencing illness or disability. A favorable decision to grant UI benefits for family caregiving reasons is far from automatic, however.40

The financial impact on working caregivers who leave the labor force due to caregiving demands can be severe. Estimates of income-related losses sustained by family caregivers ages 50 and older who leave the workforce to care for a parent are $303,880, on average, in lost income and benefits over a caregiver’s lifetime.41

Workers with eldercare responsibilities report having less access to flexible work options to do their work and caregiving activities and they perceive significantly lower job security than workers with childcare needs.42 One study found that those who left their jobs to provide eldercare believed that their employers were not flexible enough to allow them to work and carry out their caregiving responsibilities.43

Caregiving also has economic consequences for employers. It has been estimated that U.S. businesses lose more than $25 billion annually in lost productivity due to absenteeism among full-time working caregivers. The estimate grows above $28 billion when part-time working caregivers are included.44,45

Seventy-two percent of Americans ages 40 or older say allowing workers to take time away from their job or adjust their work schedule to handle family caregiving responsibilities without penalties from their employer would be helpful in improving quality of care.46 Working caregivers have also experienced employment discrimination, including being fired for reasons related to their caregiving responsibilities.47

Impact on Physical and Emotional Health

A substantial body of research has examined the impact of caregiving on the psychological and physical health of family caregivers. Findings from the Stress in America survey show that those who serve as family caregivers to older relatives report higher levels of stress and poorer health than the population at large. More than half (55 percent) of caregivers surveyed said that they felt overwhelmed by the amount of care their family member needs.48

Family caregivers of older adults experiencing depression, anxiety, and greater severity of physical health symptoms themselves (such as sleep problems, pain, or exhaustion) were considerably more likely to report substantial negative aspects of caregiving, according to an analysis of the National Study of Caregiving.49 Caregiving can be especially burdensome for some people when they worry about the range of tasks they are expected to carry out safely and well, and when they do not receive needed training or help in coping with their fears.50

Family caregiving can be especially overwhelming and stressful when caring for someone with dementia. Changes in memory, personality, and behavior (such as wandering or asking questions repeatedly) can be challenging for family caregivers. A body of research has shown that the stress of family caregiving for people with dementia is associated with high emotional strain, poor physical health outcomes, and increased mortality. There is also evidence that spouses are at increased risk of dementia themselves,51 and significantly more likely to experience increased frailty over time, as compared to non-dementia caregivers.52

Financial Impacts

Family members who take on a caregiving role for a relative with complex care needs can experience financial challenges, too. These challenges can include direct financial support for their relative or close friend, reduced ability to meet expenses, reduced savings, lost personal time from providing care, and employment consequences of family care from reduced or foregone income, lost benefits, or reduced pension.53 (See also section on Impact of Caregiving on Work.)

An estimated 3 in 10 (29 percent) American workers say they are currently providing direct financial support to a relative or friend. Among those workers, more than 1 in 5 (22 percent) provide financial help to a parent or parent-in-law.54 According to a recent study by the Pew Research Center, more than 1 in 4 (28 percent) adults with at least one parent age 65 or older says they helped their parents financially in the past 12 months.55

Nearly 4 in 10 (38 percent) family caregivers of adults report experiencing a moderate (20 percent) to a high degree (18 percent) of financial strain as a result of providing care.56 Family caregivers who provide intensive caregiving experience high burden, and those who live at a distance from their care recipient are more likely to say they experience a high degree of financial strain from caregiving.57 There is also evidence that family caregiving for parents or a spouse increases the likelihood of falling into poverty over time.58

Role of Technology

According to the Pew Research Center, the great majority (86 percent) of family caregivers have access to the Internet, compared with 78 percent of non-caregivers. Of those, more than 8 in 10 (84 percent) search online for health information to assist them with navigating the health care and LTSS systems, and to seek information to address practical and emotional caregiving concerns.59

In addition to the Internet, health information technology includes a wide range of electronic applications that individuals and their families can use to participate in their health care and supportive services.60 Evidence suggests that usage of health information technology is common for family caregivers, especially among those who do not live with their care recipient or who provide more intensive caregiving.61

In one survey of family caregivers living apart from the care recipient, nearly half (49 percent) of those using technology said that health system privacy rules impede their ability to use technology for caregiving activities.62 The federal law that protects the privacy of an individual’s medical information—the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996—is sometimes viewed as creating barriers for family caregivers to obtain information about the care recipient that family caregivers need to provide good care.63,64

RECOGNIZING AND SUPPORTING FAMILY CAREGIVERS: 4 YEARS OF PROGRESS

There is now greater recognition among policymakers, researchers, and health and social service professionals, that family caregiving is a central part of health care and LTSS in the United States today. Providing better and more meaningful supports for family caregivers—to make the complexities of caregiving tasks easier—is the right thing to do, and a social and economic imperative.

Over the past 4 years (since the 2011 Valuing the Invaluable report was released) a number of federal and state policy developments are improving awareness about family caregivers’ unmet needs and strengthening initiatives that support the well- being of caregiving families.

Federal Level

New requirements in Medicare and Medicaid provide important first steps to better identify and engage family caregivers in health care and LTSS. A movement toward person- and family-centered care,65 and research highlighting the increasing complexity of family care,66 have helped to bring about these changes.

Major Initiatives

• Congressional caucus on family caregiving: The bipartisan, bicameral Assisting Caregivers Today (ACT) Congressional Caucus was created in March 2015.67 Its purpose is to bring greater attention to family caregiving and help people live independently, educate Congress on these issues, and engage them on a bipartisan basis to help develop policy solutions. The caucus looks at family caregivers helping people of all ages who have chronic or other health conditions, disabilities, or functional limitations.

• Institute of Medicine study: The Institute of Medicine (IOM) established a Committee on Family Caregiving of Older Adults in 2014.68

It is developing a comprehensive report with recommendations for public and private sector policies to support family caregivers. The report, to be released in spring 2016, will also make recommendations to minimize the barriers that family caregivers encounter in trying to meet the needs of older adults, and to improve the health care and LTSS provided to care recipients.

• Commission on Long-Term Care: The 2013 federal Commission on Long-Term Care took an important step to elevate the national discussion about the central importance of building a better system to support people with LTSS needs and their family caregivers. Its report viewed family caregiving as a public issue that can no longer be ignored.69 It also called for national policies to acknowledge and support family caregivers, including the development of a broad national strategy to address family caregiver needs.70

Work/Family Policies

• Defining spouse under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA): Effective March 2015, the Department of Labor updated the definition of “spouse” under the federal FMLA. Federal job- protected family and medical leave benefits are now extended to eligible workers in legal same- sex marriages, regardless of where they live.71

• Workplace flexibility and paid sick leave for federal workers: At the 2014 White House Summit on Working Families,72 President Obama issued a Presidential Memorandum73 giving federal workers a “right to request” flexible workplace arrangements, and directing federal agencies to expand flexible workplace policies to the maximum extent possible. Building on these measures, the White House issued another Presidential Memorandum in 2015 that, among other measures, directed federal agencies to advance up to 6 weeks of paid sick leave for federal employees to care for ill family members, including spouses and parents.74

Medicare

• Medicare chronic care management fee:

Starting January 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began paying primary care providers (such as physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) for non-face-to-face care management and coordination activities for Medicare beneficiaries with two or more chronic conditions. The new fee includes communication with beneficiaries and their family caregivers during transitions between acute care settings and the community.75,76 Chronic care management services include development of a plan of care, communication with other health providers involved in the care of the beneficiary, coordination with home- and community-based service providers, and medication management.

• Medicare telehealth benefit: Effective January 2015, CMS expanded telehealth77 coverage for certain Medicare beneficiaries and their family caregivers in underserved areas, such as rural communities. Among the expanded telehealth services, mental health professionals (including psychologists and licensed clinical social workers) can now provide counseling services to family caregivers either with or without the Medicare beneficiary present.78

• Medicare appeals and complaint process: Effective August 2014, CMS restructured its quality of care review network to create two regional Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs), known as Beneficiary and Family Centered Care-QIO. Among other functions, these organizations serve as a point of contact for Medicare beneficiaries and their family caregivers who want to file a complaint about a hospital discharge or a lapse in quality of care, for example.79

• Medicare post-discharge transitional care management: Starting in January 2013, Medicare began paying physicians or other qualified health providers (such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants) for post-discharge transitional care management (TCM) services.80 These services can be provided within 1 month following an inpatient discharge for any Medicare beneficiary who meets specific coverage criteria established by CMS.81 Services must include communicating with the individual and/or family caregiver within 2 days following discharge, and a face-to-face visit with a community physician or other qualified health provider within 7 to 14 days (or sooner, if medically necessary).82 Medicare beneficiary and caregiver education covers self- management, independent living, and ADLs (such as bathing). Specific training on how family caregivers can provide at-home medical/nursing tasks (such as wound care) is not required.

Medicaid

• Assessing family caregiver needs for community living: In January 2014, CMS released a new rule on community living for Medicaid home- and community-based services (HCBS) programs.83 For the first time, CMS formally recognized the importance of assessing the needs of family caregivers when their assistance is part of the care plan for the person with disability. However, the new requirement relates only to one of the Medicaid HCBS authorities, the 1915(i) HCBS state plan option that allows states to expand HCBS and target services to specific populations.84

• Guidance on family caregiver assessment: The Balancing Incentive Payments Program (BIPP), established under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), encourages states to make greater use of HCBS as a proportion of LTSS spending. In its guidance to states on BIPP, CMS recommends that family caregiver needs be considered as part of the assessment process for the Medicaid beneficiary, recognizing that “these needs are typically connected to caregiver stress, a need for information and referral, support groups and/or respite care. An assessment process that incorporates components tied to caregiver needs will result in a more well-rounded assessment of the service and support needs of the whole family.”85

Other Initiatives

• New Center on Family Support: A new federally funded Research and Training Center on Family Support is bringing together experts in aging and disabilities to advance a coordinated approach for research, policy, and practice to bolster family caregivers.86

• Training family caregivers: The Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce, is establishing a geriatrics workforce enhancement program in fiscal year 2015. A main focus of the program is to develop health care providers who can assess and address the needs of older adults and their family caregivers in the community. Special emphasis will be on partnering with, or creating, community-based outreach resource centers to address the education and training needs of older adults and their family caregivers.87

• Revised hospital discharge planning guidance: Hospitals are required to follow certain procedures under the Conditions of Participation for Medicare and Medicaid. They are required to have a discharge planning process that applies to all care recipients. In May 2013, CMS issued revised guidance setting expectations that care recipients and family caregivers (or “representatives” or “support persons”) be actively involved throughout the discharge planning process, including appropriate training and referrals to community services.88 However, the guidelines do not explicitly say how hospitals must involve family caregivers or how training family members on performing complex care tasks, based on the family caregiver’s needs and capabilities, should occur. States are moving to enact legislation that provides for more specificity, as described below.

State Level

The 2014 State LTSS Scorecard reported modest improvement over 2011 in state LTSS performance for older adults, people with physical disabilities, and their family caregivers.89 Some states assess family caregiver needs as part of HCBS programs. Yet few states have any questions directed to family caregivers in their client assessment tools for Medicaid HCBS waiver programs.90 The Scorecard found that 29 states improved in legal and system supports for family caregivers, especially in the area of workplace supports and protections for the millions of workers who balance work and family caregiving. More states also implemented laws that permit nurses to delegate tasks to direct care workers to help maintain care recipients’ health and better support their caregiving families.

Policies on Medical/Nursing Tasks

• Thirteen states—Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Indiana, Mississippi, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Virginia, and West Virginia—have enacted the Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act as of June 5, 2015. A total of 29 states and territories have introduced the CARE Act in state legislatures in 2015.91 The CARE Act features three provisions:

1) the hospital must ask the patient if he or she would like to designate a family caregiver, and the name of the family caregiver is recorded when a family member is admitted into a hospital; 2) the family caregiver is notified if the individual is to be discharged to another facility or back home; and 3) the facility must provide an explanation and instruction of the medical/ nursing tasks (such as medication management, injections, wound care) that the family caregiver will need to perform at home.

• State Nurse Practice Acts usually determine the extent to which direct care workers (such as home care aides) can help consumers and their family caregivers get assistance with health maintenance tasks, known as “nurse delegation.92 Generally a state will permit family members to be trained to perform health maintenance tasks, but may not permit paid direct care workers to be taught to perform them. Such tasks include administering medications, doing tube feedings, and ventilator care. In 2011, five states (Colorado, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, and Oregon) permitted delegation of 16 key tasks.93 Since 2011, four more states (Alaska, Minnesota, Vermont, and Washington) now allow these 16 tasks to be delegated, easing the burden on family caregivers.94,95

Family Caregiver Assessment

• Rhode Island enacted the Family Caregivers Support Act of 2013 as part of the state’s Medicaid LTSS reform efforts. The law requires a family caregiver assessment if the plan of care for the Medicaid beneficiary involves a family caregiver.96

• At the end of 2012, 15 states included a family caregiver assessment as part of their Medicaid HCBS client assessment tools: Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri,New Jersey, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Washington.97

Respite Care

• Respite addresses one of the most pressing needs of family caregivers—temporary relief from caregiving tasks.98 Funding for respite care has continued to decrease in some states and increase in others. In 2015, a few states (New York, Utah, and Wyoming) increased funding for respite programs by more than 10 percent, enabling family caregivers to take some time off to recharge.99

Work/Family Policies

• Connecticut was the first state to require certain employers to provide a minimum number of paid sick days, also referred to as earned sick days, for their workers. Effective January 2012, the Connecticut law requires most employers with 50 or more employees to provide up to a maximum of 5 paid sick days per year. Eligible workers may use these days for their own illness, or to care for a child or spouse. However, workers caring for their parents are not covered under this law. on the laws enacted in San Francisco and Washington, DC.101 Localities with paid sick days laws include: Oakland, California; New York City, New York; Eugene and Portland, Oregon; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Seattle and Tacoma, Washington; and nine cities in New Jersey, including Bloomfield, East Orange, Irvington, Jersey City, Montclair, Newark, Passaic, Paterson, and Trenton.102,103

• Since 2011, 10 states or localities expanded their state unpaid family and medical leave provisions— beyond what the federal FMLA provides—to benefit more working family caregivers.104

• Connecticut and six localities expanded employment discrimination protections for family caregivers.105,106

• In September 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau and the Employment and Training Administration awarded funds to assist the District of Columbia, Massachusetts, Montana, and Rhode Island in funding feasibility studies on paid family and medical leave programs.107 In 2015, the Women’s Bureau will support additional states to conduct paid leave feasibility studies.

• Rhode Island became the third state (following California and New Jersey) to enact a paid family leave insurance program (Temporary Caregiver108

• California and Massachusetts became the second Insurance), effective January 2014. Unlike the and third states, respectively, to guarantee paid sick days for certain workers, effective July 2015. California’s law requires large and small employers to provide to eligible workers at least 3 paid sick days per year, which can be used to care for ill family members. Under the California law, the definition of “family member” is broad. In addition to time off to care for a sick child, spouse, or parent, the law also covers care for a parent-in-law, grandchild, grandparent, or sibling. Massachusetts requires private and public employers with 11 or more employees to provide their workers with up to 5 paid sick days per year.100 The sick leave can be used for illness or medical appointments for the workers themselves, or to care for the worker’s child, spouse, parent, or parent-in-law.

• A number of cities and localities have guaranteed access to paid sick days since 2012, following programs in California and New Jersey, Rhode Island workers also are protected against job loss and retaliation for taking paid family leave.109,110

• As of July 2014, California workers can take longer-term paid family leave111 to care for other ill family members in addition to care for an ill child, spouse, domestic partner, or parent. California workers can now take paid family leave to care for a grandparent, parent-in-law, grandchild, or sibling with a serious health condition.

Advance Planning and Guardianship

• When an individual, such as a vulnerable adult with cognitive impairments, is no longer able to manage his or her own personal decisions or property, the court can appoint an individual or a professional to act on behalf of the person, called guardianship (also known as “conservatorship” in some states).112 Since 2011, 22 states (Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Vermont, Virginia, and Wyoming) and Puerto Rico have enacted the Uniform Adult Guardianship and Protective Proceedings Jurisdiction Act (UAGPPJA), providing uniformity among the states.113 This law aims to help family caregivers who serve as guardians and conservators, allowing them to make important decisions for the person under guardianship as quickly as possible, and across state lines.

• Powers of attorney are important tools for delegating authority to family caregivers or others to act on one’s behalf. Since 2011, nine states (Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii, Iowa, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia) have enacted the Uniform Power of Attorney Act (UPOAA). Among other things, the law clarifies the duties of the agent and helps promote autonomy.114

THE FUTURE AVAILABILITY OF FAMILY CAREGIVERS IS DECLINING

Although the family has historically been the major care provider for older relatives and those with disabilities, the number of potential family caregivers is declining. The caregiver support ratio estimates the number of potential family caregivers—those in the primary caregiving years (ages 45–64)—for every person age 80 and older (those most likely to need LTSS).115 In 2010, the ratio was at its highest as the baby boomers aged into the prime caregiving years. The baby boomers began turning 65 in 2011. The oldest boomers start reaching age 80 in just 11 years (2026).

The caregiver support ratio has begun what will be a steep decline: decreasing from a high of 7.2 in 2010 to 6.8 potential family caregivers for every person in the high-risk years in 2015. By 2030, as the boomers transition from family caregivers into old age themselves, the ratio will decline sharply to 4 to 1. It is expected to fall further to less than 3 to 1 in 2050, when all boomers will be in the high-risk years of late life.116

Despite the looming care gap, there is a disconnect among adults between expectations for future care needs and the likely actuality of whom they would rely on for care. One recent study found that nearly 3 out of 4 (73 percent) middle-aged adults (ages 40– 65) expect their families would provide LTSS if they needed it—nearly seven times more than those expecting to use a home health agency, or to reside in an assisted living facility or a nursing home.117

The dramatic decline in the caregiver support ratio suggests that the increasing numbers of very old people—with some combination of frailty, and physical and cognitive disabilities—will have fewer potential family members on whom they can rely for everyday help. Overall care burdens will likely intensify, and place greater pressures on individuals within families, especially as baby boomers move into old age.

CONCLUSIONS

Family caregivers are an essential part of the U.S. social, health, and economic fabric. But both the complexity and the intensity of family caregiving for adults with chronic conditions and functional impairments are increasing. The 2013 estimate of the value of family caregiving is conservative because it does not quantify the physical, emotional, and financial costs of care. Despite some recent policy advances at the federal and state levels, we need to accelerate progress in adequately recognizing and explicitly supporting family caregivers.

To both address the growing care gap as the population ages and lessen the strain in the daily lives of caregiving families, more meaningful public policies and private sector initiatives are needed now. Better strategies will assist those who need care and their families struggling to find and afford the supportive services to live in their homes and communities—where they want to stay. It is essential to the well-being of our health care and LTSS systems, our economy, our workplaces, our families, and ourselves.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

National Strategy

• Develop a broad national strategy to better recognize and address the needs of caregiving families. The strategy should bring together public and private sectors to advise and make recommendations to address the challenges facing family caregivers.

Financial Relief

• Provide financial assistance for family caregivers through a federal or state tax credit (or other mechanisms) to help ease some of the financial costs of caregiving and improve financial security. In a recent national poll, nearly 7 in 10 (68 percent) family caregivers say they have had to use their own money to help provide care for their relative. Nearly 4 in 10 (39 percent) felt financially strained.118

• Consider reforms, such as Social Security caregiver credits, for time spent out of the workforce for family caregiving reasons. People who disrupt their careers for full-time caregiving responsibilities can lose substantial benefits and retirement security.

• Expand participant-directed (sometimes referred to as “consumer-directed”) models in publiclyfunded HCBS programs that permit payment of family caregivers. Such models allow consumers and their families to choose and direct the types of services and supports that best meet their needs.

Work/Family

• Strengthen “family-friendly” workplace flexibility policies that accommodate employed family caregivers, including flextime and telecommuting, use of existing leave for caregiving duties, referral to supportive services in the community, and caregiver support programs in the workplace. Such policies and benefits can enhance employee productivity, lower absenteeism, enhance recruitment and retention, reduce costs, and positively affect profits.

• Make improvements to the FLMA, such as expanding coverage to protect more workers, and expanding its scope to cover all primary caregivers, regardless of family relationships. Adopt such policies at the state level that exceed the current federal eligibility requirements.

• Optimize worker productivity and retention by promoting access to paid family leave. Many working caregivers cannot afford to take unpaid leave to care for an ill family member. In addition, employers should be required to provide a reasonable number of earned sick days that can be used for short-term personal or family illness.

• Protect workers with family caregiving responsibilities from discrimination in the workplace. This should include requirements to provide reasonable accommodations to family caregivers.

• Advance public awareness campaigns at the federal, state, and local levels to educate the public about family caregiver discrimination in the workplace, and about all aspects of family leave policies, including the FMLA and paid family leave in states with such policies.

Caregiver Support Services

• Promote assessment of family caregivers’ needs (at the federal and state levels) as part of a person- and family-centered care plan, such as through publicly funded HCBS, hospital discharge planning, chronic care coordination, and care transition programs. Family caregiver assessment tools should, at a minimum, ask family caregivers about their own health and well-being, level of stress and feelings of being overwhelmed, and the types of training and supports they might need to continue in their role.

• Ensure that all publicly funded programs and caregiver supportive services at the federal, state, and local levels reflect the multicultural and access needs of the diverse population of family caregivers.

• Expand funding for the National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP) to keep pace with demand and better address the unmet needs of caregiving families. Federal funding for caregiver support services was reduced about 5 percent from $153.9 million in FY 2011 to $145.6 million in FY 2015.119

• Provide adequate state and federal funding for respite programs, including the federal Lifespan Respite Care Act, which is inadequately funded at only $2.4 million in FY 2015. Lifespan respite programs assist family caregivers in gaining access to needed respite services, train and recruit respite workers and volunteers, and enhance coordinated systems of community-based services.

• Widely disseminate, and implement locally, caregiver support services that are shown to be effective. Such programs should better address the practical and emotional needs of caregiving families and improve outcomes for the family caregiver and the care recipient.

Health Professional Practices

• Encourage primary care providers and other health professionals to routinely identify Medicare beneficiaries who are family caregivers as part of the Health Risk Assessment in Medicare’s annual wellness visit. This would better track the beneficiary’s health status and potential risks from caregiving, including physical strain, emotional stress, and depression.

• Ensure that electronic health records include the person’s family caregiver as a point of contact, whenever the individual’s care plan depends on having a family caregiver. This would facilitate better communication among individuals, family members, and providers.

• Adopt legislation in the states, such as the CARE Act, that requires hospitals to give an individual admitted to a hospital the opportunity to designate a family caregiver and have that family caregiver’s name placed in the medical record. Legislation should also require hospitals to notify the family caregiver of an impending transfer or discharge, and provide instruction to the family caregiver about care tasks the family caregiver may be asked to perform as part of the individual’s discharge plan. Communication strategies with family caregivers should be built into the hospital structure as a central component of good care.

• Enable registered nurses in states to delegate medical/nursing tasks to qualified direct care workers who provide assistance with a broad range of health maintenance tasks. Such nursing practices can ease the burden on family caregivers.120

• Develop educational programs, including continuing education, to prepare health care and social service professionals with the technical and communication skills and competencies to integrate family caregivers into the care team, and engage them as partners in care. Develop tools and training that are culturally appropriate and targeted to caregivers’ unmet needs.

Advance Planning and Guardianship

• Establish comprehensive guardianship and power of attorney reforms to help protect vulnerable adults and provide their family caregivers with the tools they need to make important decisions for the care recipient as quickly as possible, regardless of where they live.16

Research Recommendations to Inform Policy Development

• Promote standard definitions of family caregiving in federally funded and other national and state surveys to better characterize the size, scope, tasks, and outcomes of family caregiving.

• Improve data collection on employed caregivers with eldercare responsibilities (including surveys conducted by the Department of Labor, Department of Health and Human Services, and Department of Commerce) to ensure that challenges about work-family conflict and access to workplace leave benefits and protections are addressed.

• Develop a common definition and unit of measurement for respite care (at the federal and state levels) as a useful indicator of LTSS system performance. Respite care is one of the most commonly requested caregiver support services. But definitions of respite vary among programs and states, making comparisons difficult.

• Advance measures of “family caregiver experience” and “family caregiver engagement” that meet criteria for endorsement by the National Quality Forum. These measures could be used by health care and LTSS providers and payers to examine improvements in quality of care for the care recipient and the family caregiver. Research is also needed to increase cultural sensitivity of health and social service professionals working with multicultural caregiving families.

APPENDIX A: SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY OVERVIEW

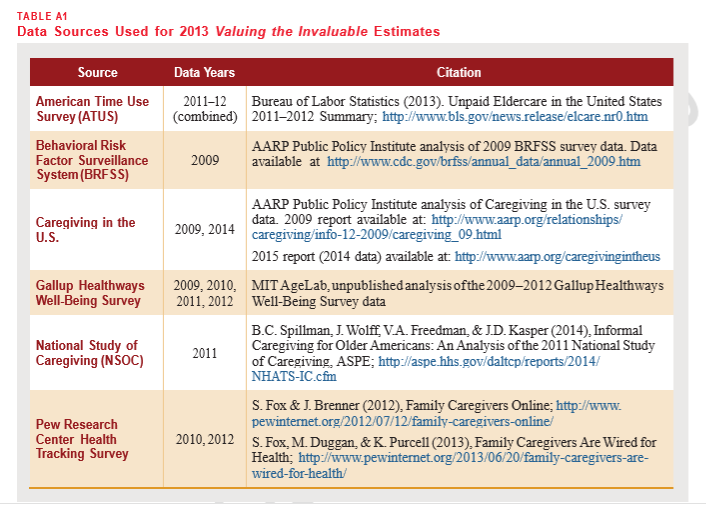

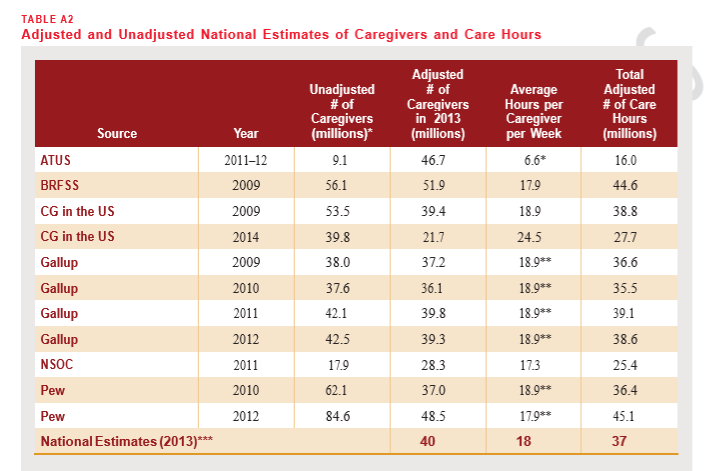

The Valuing the Invaluable estimates of 40 million family caregivers, 37 billion care hours, and $470 billion economic value in 2013 are based on a meta-analysis of 11 surveys of caregivers between 2009 and 2014.

Each source series (see table A1) has a different definition of caregiving, determined by the question used to identify caregivers, and other characteristics of the survey. Using detailed data on caregivers, care recipients, and the care relationship from three sources (BRFSS and both years of Caregiving in the U.S.), each source definition was adjusted to a common definition for consistent comparison:

• Caregiver age 18+

• Care recipient age 18+

• Providing assistance with ADLs and IADLs

• Providing care currently or within the last month

• Year 2013

More detail about the sources, adjustments to the common definition, and other methodology can be found in the Detailed Methodology document online at http://www.aarp.org/valuing.

The meta-analysis approach is preferred because it takes into account more information than any one particular survey. As well, the adjustment to the common operational definition brings the different estimates into a tighter cluster (see table A2). This increases our confidence that the Valuing prevalence, hours, and economic value estimates are not significantly under- or over-estimated based on a single outlier data source.

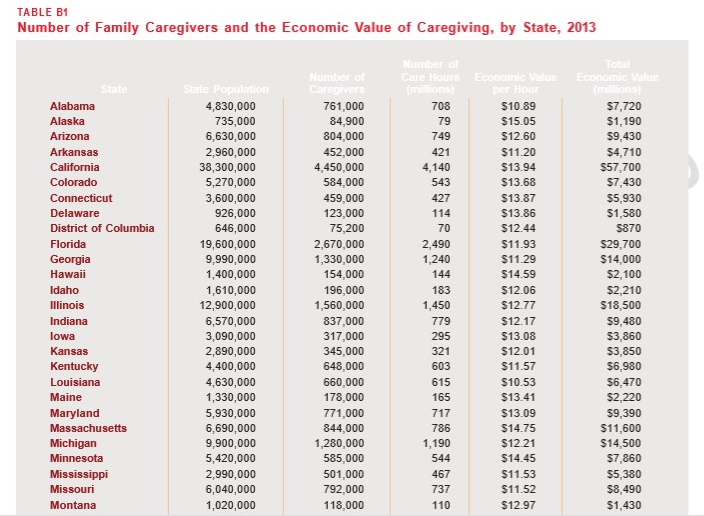

In order to present consistent state and national estimates of the economic value of caregiving, the number of family caregivers and the economic value of caregiving were estimated separately at the state level, and then summed to get national estimates. At the state level, the economic value was calculated as (number of caregivers in 2013) × (hours of care per caregiver per week) × (52 weeks/year) × (economic value of one hour of family care).

The number of family caregivers was based on a weighted average of the 11 data sources, adjusted to the common definition, and multiplied by a state factor based on five sources with state-specific prevalence data (BRFSS, all 4 Gallup years) to account for significant variation in the age structure and age- adjusted prevalence of caregiving across states.

The economic value of 1 hour of care was estimated at the state level as the average of the state minimum wage, median home health aide wage, and median private pay cost of hiring a home health aide.1

Data were not available to estimate the number of hours per week at the state level, so a single estimate of 18 hours per week was used for all states.

The national average value per hour of $12.51 is the average value for all care hours across all states. In the states, the average value per hour ranges from $10.53 in Louisiana to $15.05 in Alaska (see appendix B for state data).

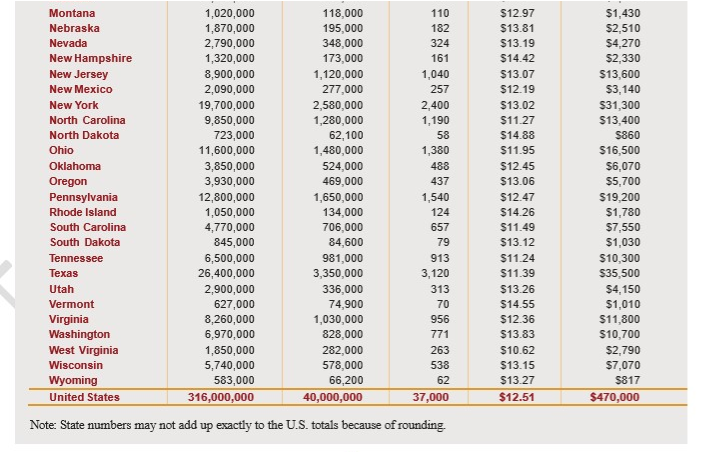

APPENDIX B: STATE DATA

The most important factor in determining the number of caregivers in each state is state population. However, caregiving prevalence also varies among states, reflecting differences in the age structure of the population, rates of disability and chronic health conditions, and cultural and economic factors. There is also significant variation in economic value per hour among states. Table B1 (page 19) presents estimates of the number of caregivers, economic value per hour, hours of care provided, and total economic value of caregiving in every state and the District of Columbia.

To see the full article click here and to see the full cited works

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful review and suggestions of our AARP colleagues: Debbie Chalfie, Carlos

Figueiredo, Wendy Fox-Grage, Ilene

Henshaw, Harriet Komisar, Keith Lind, Enzo

Pastore, Rhonda Richards, Elaine Ryan, and Deb Whitman.