Sixteen months ago, 1.3 million Oregonians voted in favor of a drug-decriminalization law that promised to revamp the state’s abysmal treatment system and dedicate a windfall of public dollars for services to help people grappling with addiction — nearly 1 out of 5 adults in Oregon.

After a year of meetings, however, the innovative council tasked by voters to spend that money is floundering.

Interviews and documents obtained through public records requests indicate widespread concerns about how the Measure 110 Oversight and Accountability Council is functioning.

Those concerns, which have been bubbling up in recent meetings, came to a head on Feb. 9 when two members of the council threatened to quit, questioning whether the council’s process for awarding grant money allows members’ personal biases to give some organizations an unfair advantage and opens the door to funding organizations who won’t be able to use the money effectively.

“I don’t agree with this process at all,” said council member Caroline Cruz. “I don’t think we’re being realistic.”

The council hit pause, canceling its meetings, and now awaits a closed session on Feb. 23, when lawyers from the state justice department will advise council members on the best path forward.

Drug decriminalization advocates have lauded the council for putting those harmed most by the criminalization of addiction in charge of spending the windfall of marijuana-tax dollars the measure diverted toward treatment and recovery in Oregon.

The Lund Report’s review of the council’s operations in recent months, supplemented by conversations with participants and close observers, suggest that the inexperience of its members and a lack of information and support provided by state officials are contributing to the council’s struggles.

Whether these issues indicate growing pains or potentially crippling flaws remains unclear.

But the stakes are high: The council is tasked with spending $300 million of public funds in every two-year budget cycle. Meanwhile, nearly 650,000 Oregonians aged 18 and older are estimated to struggle with substance use disorder, according to new data from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

An Unprecedented Approach

In addition to making Oregon ground zero for decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of hard drugs such as cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine, Measure 110 was advertised as a way to bolster treatment and recovery services in a state that, according to the same federal data, ranks last nationally in access to treatment. Just over 18% of Oregonians need but are not receiving treatment for substance use, the 2020 survey found.

To address these problems, the Drug Addiction Treatment and Recovery Act set up a system to award providers with grant-funded contracts that state officials would oversee.

The measure also explicitly laid out the make-up of the council that would control how the funds are spent: Its voting members would include people experienced in substance use disorder treatment, at least three members of communities that have been disproportionately impacted by drug related arrests and criminalization, someone who works in harm reduction, an academic drug policy researcher, a drug policy advocate, at least two recovery peers and at least two people who suffered or suffer from addiction, as well as a physician specializing in addiction, a social worker, a housing services specialist and a person representing coordinated care organizations.

The resulting council is more diverse and representative of impacted communities than even the measure’s framers had prescribed: The majority of the 18 voting council members fit into several required categories. Most are in recovery from substance use disorder, and many have been incarcerated.

For many, their experiences drive their determination to reform Oregon’s treatment system. Morgan Godvin, for example, is a 32-year-old who founded the harm reduction provider, Beats Overdose, is a drug policy researcher with Health in Justice Action Lab, is in recovery from substance use disorder and is a member of the LGBTQ+ community.

She was arrested in Multnomah and Washington counties in 2013 and 2014 for felony possession and delivery of heroin and consequently spent time in federal prison. She’s said she’s watched multiple friends who used drugs go in and out of jail before ultimately dying of overdose — an illustration to her of how incarceration does not solve substance use disorder.

Members’ dedication to public service has kept them going through arduous and repeated meetings.

Until this past December when per diems were raised to $151 per day, members were paid $30 per day if they were not being paid through their employers. Godvin said it can take months to receive payment.

Their dedication has also contributed to the time consuming disagreements and impassioned debates that have become characteristic of the council’s process, at times forcing the extension of deadlines.

While community advisory groups and the sometimes-messy proceedings that come with them are not new, giving one the purse strings to $300 million a biennium is.

“From the beginning, we were doing something new,” Godvin told The Lund Report. “There was no model we could look towards to shape our path forward, because it had never been done before.”

The Work Stoppage

After Measure 110 went into effect last February, the Oversight and Accountability Council oversaw the distribution of $31.4 million in initial grant funding.

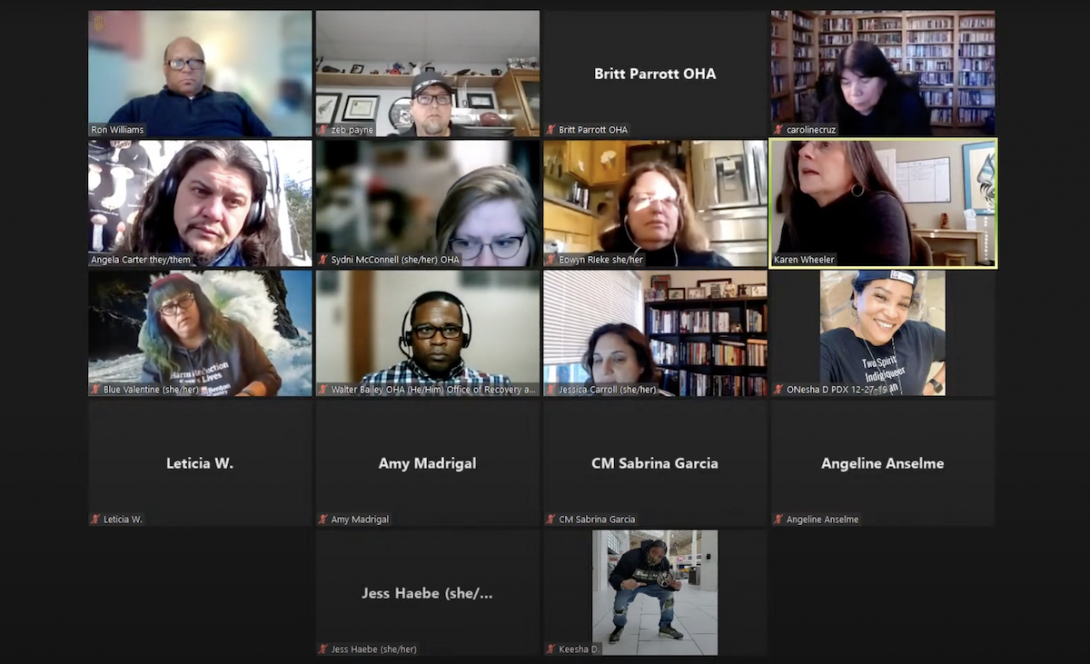

But for much of the past year, the council has met on Zoom weekly, sometimes more, to create a more involved grant program from scratch that’s designed to follow through with the law’s call for coordinated treatment and recovery networks in each region of the state.

Now, after months of crafting it, the council is putting its new process to work while deciding how to award $270 million in grant funding to substance use disorder service providers that, in many cases, direly need it. Another $10 million allotted to tribes will also be distributed.

That’s why the dispute at the Feb. 9 meeting was more consequential than most.

On the agenda for the subcommittee meeting that afternoon was voting on a stack of 63 applications. There are 281 applications in all, seeking more than $400 million in funding.

Each application had been evaluated by two council members with the assistance of an Oregon Health Authority staffer. An evaluator would present their team’s recommendation for or against funding the application, and the subcommittee would vote. The plan was to take the list of winners to the full council for a final vote the following week.

Issues arose when council member Karen Wheeler recommended against funding the 11th application on the list, from Medicine Wheel Recovery in Columbia County. Wheeler is the CEO at Greater Oregon Behavioral Health, Inc., which administers behavioral health Medicaid benefits and co-owns Eastern Oregon Coordinated Care Organization.

She told the council that Medicine Wheel Recovery’s application didn’t align with the council’s criteria and that it was poorly written.

But when several members of the subcommittee voted against her recommendation, saying that because the nonprofit was small and serves Native Americans, they should consider funding it anyway, Wheeler balked.

“I have a, really, problem with this process. I objectively reviewed an application, and I did not think it was a good application,” said Wheeler, “And if we’re going to be subjective, I don’t know if I can continue. I’m going to have to completely remove myself from this process.”

Other council members argued the process for evaluating grants might not capture the grant writers’ intent. O’Nesha Cochran, of Brown Hope, said the council should be funding organizations that are grassroots, “but don’t have that much experience with contract writing.”

Council Tri-Chair Ron Williams asked, “Is it a well intended, but poorly written proposal?”

“We’re not starting with a level playing field,” said Zebuli Payne, of Phoenix Wellness Center. “I know there was technical assistance, but we’re talking about a completely different language than a lot of these providers are used to speaking. They (may not) speak grant language, so I think it’s tough for those providers to stack up against a well-established professional grant writer.”

Council member Cruz noted that there was another provider in Columbia County serving Native Americans, so that was not a gap Medicine Wheel Recovery would be filling.

She also echoed Wheeler’s concerns about a lack of objectivity in the process. Wheeler and Cruz, who is the Health & Human Services general manager for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, are the only active council members who appear to have any experience with grant processes. They explained to the council that the process had to be objective to avoid making the council vulnerable to legal challenges from applicants who are not awarded funds.

“I’m with Karen. I think I’m going to withdraw, too,” Cruz said. “People are coming on here and making me feel uncomfortable, to be quite honest, like ‘Oh you’re wrong, you’re not being sensitive to these people who can’t write grants, and you’re not being sensitive to the people who are the grassroots, and they haven’t been given the opportunity.’

“If you want to fund everyone, then fund everyone,” Cruz added. “If they can’t write a good application, that’s a good indication that they’re not going to be able to put this program together. And I’m talking from years of experience here.”

Over the course of the debate, Williams changed his vote three times, eventually abstaining, causing another debate over whether he could change his vote after it had been tallied.

Eventually the subcommittee determined the process needed to be taken up with the full council, and the meeting adjourned without the review of any additional applications.

All the council meetings scheduled to follow were abruptly canceled.

Lack Of Technical Experience, “Hands-off” Approach

The Oregon Health Authority, to some extent, oversees the Oversight and Accountability Council. Agency employees select council members from a pool of applicants and staff the council meetings with a public health analyst and a Measure 110 program manager who facilitates and acts as a go-between.

Internally, the health authority has about five other staff assigned to Measure 110 that sometimes make appearances. It has several unfilled positions, and has recently asked the Legislative Fiscal Office to add another eight positions to help it manage Measure 110 contracts. The agency’s Behavioral Health Director Steve Allen attended council meetings as a non-voting member early on, though his attendance has dropped off.

The health authority has offered assistance to the council along the way, though observers have suggested it has not provided adequate guidance given the scope of the council’s tasks and the intensity of its struggles.

Some say the agency’s leadership is trying to respect the independence of the council and the measure’s intent for a community-driven process.

“It is the Oversight and Accountability Council that plays the lead role in decision making,” Allen said during an interview, “and our role at OHA is to support that decision making and to respond to requests of information that they need to be able to make the best decisions possible.”

This past year, the council spent months constructing a complicated and lengthy request for proposal that was used to solicit the grant applications it’s now considering, as well as the checklist members use to evaluate the applications, called a “rubric.” The process lacks the numerical scoring system often used to award funds.

“I have never written a request for grant proposals. I have never constructed a rubric,” Godvin told The Lund Report. “It’s highly specific. I wish that we would have been provided a little bit more structure when it came to that process.”

Council Tri-Chair LaKeesha Dumas, who identifies as a Black person with lived experience in long term recovery, has a different view. Dumas said the health authority has provided the council with “the information it has.”

During the same interview, Allen acknowledged that the agency has not given council members information about gaps in regional services other than residential treatment beds, because the health authority does not have that information. It’s up to community members to provide that information in the grant applications, he said.

“We are the ones who created, voted and approved all the facets of what’s in the rubric, what’s in the RFP. And, we did it with a lot of discussion, a lot of meetings. With whatever assistance from OHA, from subject experts — on contracts versus grants to other things like, we have got that,” said Dumas, who is also an employee of the Multnomah County Mental Health and Addictions Services Division.

“In a way, we were trying to reinvent the wheel,” Godvin said, “I just know, from how I've seen it affect applicants and reviewers, that the process needed to have been clearer.”

Godvin said that from the council’s start, “there has been a high degree of confusion.”

Changing directives, a lack of clarity and quickly approaching deadlines that forced aggressive timelines have all posed challenges.

Participating in a grant program — let alone designing one — is new territory for the vast majority of council members.

“Written in the law, this is supposed to be a community-led initiative,” Godvin said. “I think that has been a source of tension: How much do we guide ourselves versus how much does OHA provide us guidance?”

Some critics are more pointed.

An employee of one Oregon county involved with an application spoke to The Lund Report on condition of anonymity because the application process is still open.

The process has been “incredibly frustrating,” the person said.

“On one level, I just feel like OHA has not provided any kind of staff support or expertise to help the oversight committee get this money out the door,” they said. “Rightfully so, the advocates headed it up with practitioners, people with lived experience, people who understood what is needed for treatment. They didn’t put up a bunch of people who give out grant money, or who can run a government bureaucratic process. And so this poor board has gotten no support in doing this work, I mean, it’s unbelievable.”

The county applicant said they’ve been watching the council’s progress, and there was never any clear process set up for it to follow.

“That was never done. It was kind of like, ‘OK, you practitioners and lived experience, how do you want to give out $300 million?’ It's just, it's really amazing.”

Oregon Health Authority is aware of the criticism.

“We’ve also heard reports of frustration at the community level about the process and in responding. That being said, I think there were three one-hour webinars, lots of engagement, email communication,” Allen said. “Could OHA have done better? Of course. We’re always looking for ways that we can do better. But acknowledging this is a new process. The voters passed Measure 110, designed it specifically to provide the ability to create and direct these funds to community, in the hands of people with lived experience. And we 100% support that approach.”

Tony Vezina, executive director of 4D Recovery, co-chair of the state’s Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission and grant applicant, has also been tracking the work of the council. He said the turmoil during the Feb. 9 meeting didn’t surprise him.

“I would like to acknowledge the members’ civic service and commitment to this process,” he told The Lund Report in an email. “It also seems that Oregon Health Authority is providing a ‘hands-off approach’ as a means to center on those with lived experience. Given the scope of the measure and the council’s responsibility, it is understandable to me that it would take time and be a little ‘messy.’”

He said he trusts the council and the Oregon Health Authority will get the job done.

“I have really witnessed a major shift in the way the State of Oregon is investing in community-based organizations.” He said. “I think we will get there.”

‘Mass Confusion’

For treatment and recovery service providers seeking grant funding through Measure 110, the application process has become a source of stress and frustration.

The grants are aimed at funding Behavioral Health Resource Networks, or BHRNs, which can be composed of several organizations working in alignment in the same region or one provider that meets a long list of criteria including a variety of services.

At the outset of the application process last fall, a webinar for applicants left many providers bewildered.

During a Dec. 1 meeting of the council, Wheeler told the group she’d been copied on emails and contacted by applicants who were unsure whether networks could apply.

“There is mass confusion around that, and time is clicking away,” she said. “There have been tears, there have literally been people crying, especially people — from what I’ve heard — community-based organizations, who represent exactly the kind of organizations that we want to have in this BHRN. They are just like, ‘we can’t do this, we wanted to be part of a network.’”

One would-be applicant told The Lund Report she also found the process confusing.

Amy Ashton-Williams, executive director at Oregon Washington Health Network, said she tried to apply for $18.7 million in grants for programs in Union and Umatilla counties, but sent the application to the wrong address. She blamed herself for the error, saying she failed to read an updated version of the “frequently asked questions” document. But regardless, she said, the application process was “way more complicated” and “difficult to understand” compared to when she applied for and won a Measure 110 grant last year during the initial round.

“Just talking to some other small, community-based organizations — this was a heavy lift for them,” she said. But she also said she gets it.

“This is all brand new, Right? This is brand new funding, this is brand new — get money out the door as quickly as possible.”

Allen said the process is about “transformation” more than anything, adding that many Oregonians are just not seeking services.

“Measure 110 folks, the OAC, are all about transforming. They’re asking the very hard questions about how do we engage with people differently? How do we actually build a system that people want to be involved in these treatment services, that they feel welcomed, they feel seen, they feel understood? All of that has taken a tremendous amount of thought and effort. And we have the experts on the council help shape those services. I understand that that can be frustrating for traditional community providers. But frankly, we need to do the work differently, and that’s what this is about.”

He also said the large stack of applications indicates that the council didn’t do it wrong — organizations applied, whether it was challenging or not.

Godvin, the council member, described getting “earfuls” from potential applicants about the way the grant application process was presented.

“Historically, especially with culturally specific groups, or lesser funded organizations, or harm reduction, there has been a great distrust of government,” she said. “And that's why I think the (Oversight and Accountability Council) is so powerful — because it has an unprecedented level of representation of racial and cultural diversity of people with lived experience. So we really have an opportunity here to sort of mend fences.

“And yet, this process was rife with confusion in a way that did harm, ultimately, to the community we are trying to serve.”

In The Dark

While the Oversight and Accountability Council selects grant winners, it doesn’t provide oversight of their work as its name would suggest. Instead, three policy analysts at Oregon Health Authority manage and monitor the grant agreements, according to agency spokesperson Aria Seligmann.

But as the council evaluates grant applications under review for fund distribution this spring, its members have been in the dark as to whether the nonprofits and agencies that won portions of the $31.4 million in grants last year are living up to their proposals. This poses a problem because many of those same grantees are asking for additional dollars from the council now.

Council member Amy Madrigal, a mental health specialist in eastern Oregon, expressed frustration with this during a council meeting on Dec. 22.

“We talked about sustainability in the grants, we want these to be sustainable over time,” she said. “I don’t recall us reviewing any of the past grants that we decided on last time. I haven’t seen a review of any of those.”

During a council meeting on Jan. 19, another council member also pointed out the need for more information from the health authority.

“We are called the Accountability and Oversight Committee, and it seems as though we have gotten very little information about what these organizations have actually done,” Blue Valentine, a harm reduction service provider in Albany, told the group. “Based on the information I have, I don’t have a good idea of who should get more funding and who shouldn’t.”

The health authority presented the council with an aggregated overview of last year’s winners’ progress two weeks prior to Valentine’s comment, but it contained no grantee-specific information. At one point during the presentation, its author, a Measure 110 public health analyst for the health authority, Onelia Hawa, noted the agency had decided to “anonymize” the information before presenting it to the council.

The main problem? Lack of clarity on reporting requirements. Some grantees submitted detailed data and others, loose narratives, Hawa told the council. Many haven’t spent all their funds yet or filed complete reports.

In other words, no one has a clear picture of how the millions that were spent last year helped people — or didn’t. But the individual progress reports — or grantee specific information — could have helped the council to decide whether an second-time applicant should be funded again.

While grantee progress reports must be disclosed under Oregon’s public records law, the health authority had not shared them with the council.

Measure 110 Program Manager Angela Carter said the council has not been supplied with those reports because its rules do not allow members to take into consideration the status of earlier grants when deciding who to award with money.

To address the situation, uniform reporting requirements will be required moving forward, according to discussions between health authority staff and the council during its weekly meetings. And, the council will then receive regular updates regarding grantee performance.

Godvin noted that the agency is facing the same staffing shortages felt across the country.

“There's definitely been a lack of structure and guidance from the Oregon Health Authority,” Godvin said. “And I'm not blaming any one individual for that. The task they had before them was behemoth.”

When Will Grants Be Awarded?

Now, as the council prepares to take up its work again, it’s not clear how its struggles might affect its timeline for getting grant funds out the door, or how the award decisions will be made moving forward.

Meanwhile, hundreds of providers around Oregon are waiting for money to fund substance use disorder services ranging from peer support, housing and harm reduction to behavioral health workforce expansion.

Before it paused its work, the council was already a month behind its original timeline for grant evaluation.

Oregon Health Authority spokesperson Jonathan Modie told The Lund Report that it’s “unclear at this time if there will be a delay, and for how long” in getting this round of funding to providers. “It is still our goal to award as soon as possible,” he said in an email.

It’s also unknown whether the pause will lead to a larger recognition of the challenges facing the council or prompt the development of a more effective approach.

Godvin, for her part, is resolved.

“I understand the confines of circumstance,” she said, “and we must do better.”

Update Feb. 24: After hearing from state attorneys during a closed session on Feb. 23, the Measure 110 Oversight and Accountability Council reconvened for a public meeting to adopt a new process for voting on grants.

Each application will still be reviewed by a team of two council members, however the subcommittee will review each evaluation rubric, or checklist, before voting “do pass” or “do not pass” on each application. And, the full council will have access to all the evaluation rubrics and proposals should more information be needed before it casts the final vote on funding.

Voting will resume once all the rubrics have been filled out completely, which could be as early as this Friday, Feb. 25.

The council does not yet know how the work stoppage will impact the timeline for getting grant awards out the door, but plans to notify applicants when that information becomes available.

We’re closely tracking the implementation of Measure 110 and its impacts on the behavioral health care system in Oregon as part of a reporting fellowship sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists and supported by The Commonwealth Fund. If you have a tip or comment that you think would be helpful, please contact Emily Green at [email protected] or enter your tip into this form.