For decades, many residents of Eastern Oregon’s Morrow and Umatilla counties have relied on well water contaminated by nitrates, chemicals linked to cancers and thyroid disease — and especially harmful to infants.

On Friday, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, the Oregon Department of Agriculture, the Oregon Water Resources Department and the Oregon Health Authority released an eight-year Nitrate Reduction Plan that outlines short-, medium- and long-term goals on how each state agency will work to lower nitrate levels in Eastern Oregon.

The ultimate goal is to reduce nitrate concentrations below 7 milligrams per liter — below federal standards in the Lower Umatilla Basin Groundwater Management Area.

But even as the state looks to change the practices that led to contaminated drinking water wells, residents may not see results until the 2030s. A local organization says the plan lacks clear and effective strategies like specific timelines to reduce nitrate contamination and enforced regulation from state agencies.

“Generations of people have grown up in the lower Umatilla basin, and the time that the state has managed to put together what they’re calling a nitrate reduction plan, and in all that time, it has only gotten worse,” said Kaleb Lay, director of policy research at Oregon Rural Action, an advocacy group that’s been at the forefront of the nitrate crisis in the region.

The governor, however, applauded Friday’s announcement as progress.

“The state of Oregon has dedicated millions in resources to address this drinking water crisis and has developed a formal plan outlining the state’s role and timelines in supporting remediation and mitigating future deterioration of the groundwater supply,” Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek said in a statement. “This is a complex problem with no easy solutions – and it will take collaboration amongst all players to see meaningful change in the Basin. The state is committed to this ongoing work.”

Nitrate contamination has been an issue in the Morrow and Umatilla counties’ groundwater for more than 30 years, with data showing the levels have only grown since it was first documented. Groundwater is the main source of drinking water in the region. The multi-agency plan comes as residents, local organizations and state officials have called for more action on the decades-long issue.

For the past two years, Morrow and Umatilla counties have seen forward momentum. Officials have tested more wells and delivered bottled water to homes with the most contaminated drinking water as well as re-working industrial wastewater permits to limit the amount of wastewater it can apply in nearby farmland.

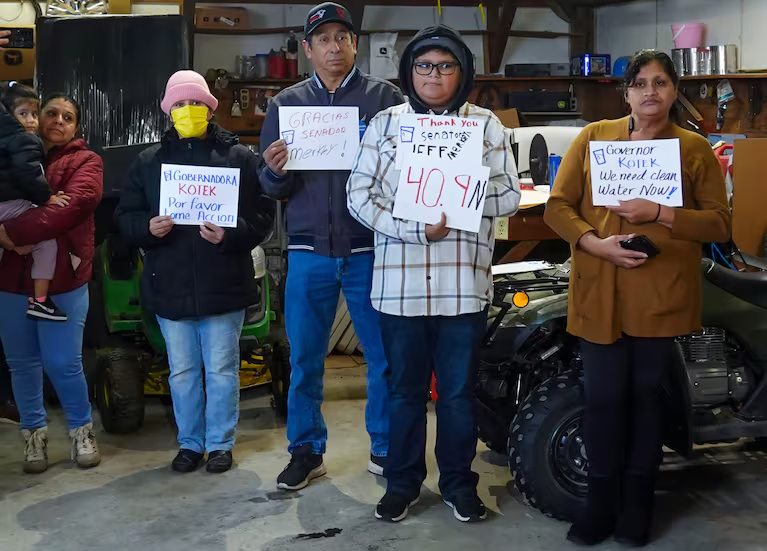

But local residents still say state leaders aren’t moving fast enough, and they want to ensure those leaders seek community input as the plan moves forward. A group of residents filed a lawsuit against some of the basin’s top farms and food processors, alleging they were directly responsible for their poor water quality. A judge is scheduled to decide whether the lawsuit can move forward on Oct. 29.

According to the newly released plan, Oregon will monitor efforts to update well monitoring and nitrate leaching data, continue free testing of domestic wells, and create new rules for irrigated farming within the impacted areas to implement by 2026. The state also said it will adjust strategies, as needed to ensure results.

The Department of Environmental Quality, the Department of Agriculture, the Oregon Water Resources Department and the Oregon Health Authority will need to work with the U.S Environmental Protection Agency, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation as well as Morrow and Umatilla counties, their city governments, businesses, residents and community groups for the plan to succeed.

“Cleaning up the area’s groundwater nitrate contamination will take decades,” according to the plan. “The most effective and feasible way to clean up groundwater contamination of this scale is to control the sources of pollutants so that, over time, clean water cycles into the groundwater system, diluting and eventually replacing contaminated water.”

An eight-year plan

At a meeting Thursday ahead of the plan’s release, Isaak Stapleton, the director of the natural resources program area for the Oregon Department of Agriculture, told local government officials that there would be no “pie in the sky” ideas coming out of the state.

“What are the things that we can do in this space with the resources that we have?” he asked. “It will still take resources to do what’s in there, but you’re not going to see these crazy initiatives.”

Still, all four state agencies involved pledged to make notable changes to how they can better handle nitrate contamination.

One of the most notable changes came from the Department of Agriculture. The agency said it will create a compliance plan for irrigated farming. The plan calls for creating specific thresholds for soil nitrate levels, requiring recordkeeping for nitrate applications and testing those levels post-harvest. After collecting public feedback on the rules that will govern these efforts in 2025, the department intends to implement them in 2026.

Justin Green is the executive director of Water for Eastern Oregon, a member group of agricultural businesses in the Lower Umatilla Basin. He praised the Nitrate Reduction Plan but said farmers are waiting to see what the new soil monitoring rules will look like. He also added that many farmers are already monitoring nitrates in ground soil.

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality will give its data a much needed update. The agency said it will update much of its decades-old data, which would result in updates to a 2011 analysis on nitrate leaching that currently shows irrigated agriculture as the largest nitrate contributor. The agency will also continue to test about 30 wells within its monitoring system and provide an updated trends analysis in the region that will show changes in water quality over time.

The Oregon Health Authority will expand its outreach and education to the community about drinking high levels of nitrate contamination and what those health impacts could be.

That agency will also continue providing free domestic well testing, free water deliveries for households that test 10 milligrams per liter or higher and free water filtration systems for households that test between 10 to 25 milligrams per liter, and share out the data.

Though the plan indicates Oregon agencies will need to apply for federal grants to achieve some of their goals, like creating a new public water system for impacted wells, it is not clear how most of the agencies’ goals will be achieved without additional funding from the state.

The governor’s next biennial recommended budget will be released by Dec. 1.

Dan Dorran, a Umatilla County commissioner and a member of the Lower Umatilla Basin groundwater committee, said he didn’t think state lawmakers should change the state’s nitrates policy through legislation.

“There’s going to be a lot of legislators that want to stick regulatory powers into a (groundwater management area) and I do not want to fight that battle right now ... ,” he said. “We’re not going to regulate ourselves out of this problem. We’re going to have to do research and perform to get ourselves out of this problem.”

Jose Garcia, a groundwater committee member who represents the public, said many residents were still angry and confused. Whatever plan the state advanced, he said, leaders would need to keep the community informed.

A plan to make a plan

Lay, with Oregon Rural Action, said although the organization is excited to finally see the plan, it still lacks specifics.

“I think specific details are not too much to ask for at this point, after it’s been going on for 34 years,” he said.

ORA has helped conduct hundreds of household well testing in the area and has helped educate and inform residents about nitrate contamination.

“I don’t think we ever would have gotten here without the hours and hours and hours of work the people who are affected by nitrate have put into demanding change and getting this, so a good moment but I really wish that the plan looked more like an actual plan,” he said.

Lay said the plan reads as an inventory of things state agencies have attempted in the past 34 years. He says he would have liked to see more specific details, like timelines and regulations proposed for reducing the amount of wastewater that can be irrigated on nearby farmland during the winter months. Or a better understanding of how the state department of agriculture will enforce regulation of irrigated agriculture especially on thousands of acres of private farmland.

Overall, Lay said, local community members should have been able to be part of the process of creating this plan.

“I really hope that the state starts to listen to them, because they know this area. They know what is happening to them,” he said. “They know how it has affected them and their communities better than anyone else ever will and if we really want to solve this, they should be at the center of it, and they should have from the start.”

The state will be accepting ongoing public feedback on the plan and officials said they will update the plan to reflect changes. The state also pledged to publish an annual report detailing its progress. A Spanish language translation of the plan can be found here.

This article was originally published by Oregon Public Broadcasting. It has been republished here with permission.