Xan Hawkes spoke in a tone just above a murmur while slouching in a chair inside a room resembling a doctor’s office. Hawkes, whose hair was graying, was living out of their car and trying to get over a case of strep throat that was getting in the way of their search for a food service job.

Hawkes (who uses they/them pronouns) explained that their situation got worse when the backpack containing strep throat medication was stolen while they were taking a nap in a park. Hawkes also recalled becoming nauseous after only having candy to eat with their medication.

Listening to Hawkes’ story were Emily West and Melissa Yates. Clad in purple nurse’s scrubs, they took turns asking about Hawkes, suggesting resources and asking about friends and family who could help. Hawkes had a more immediate worry: how to pay for the replacement medication.

After West assures Hawkes there will be no charge, a voice comes over the intercom summoning her and Yates back to a classroom down the hall.

“How did that go?” asked Ali Newhall, a faculty instructor at the University of Portland School of Nursing, who was watching how they handled Hawkes with the rest of their fellow students.

Nursing simulations, like this one, have taken on new importance over the last year as schools have struggled to produce increasingly in-demand nurses. The COVID-19 pandemic brought new safety protocols and strains on hospitals and other settings where nursing students would normally receive hands-on training on their way to becoming licensed.

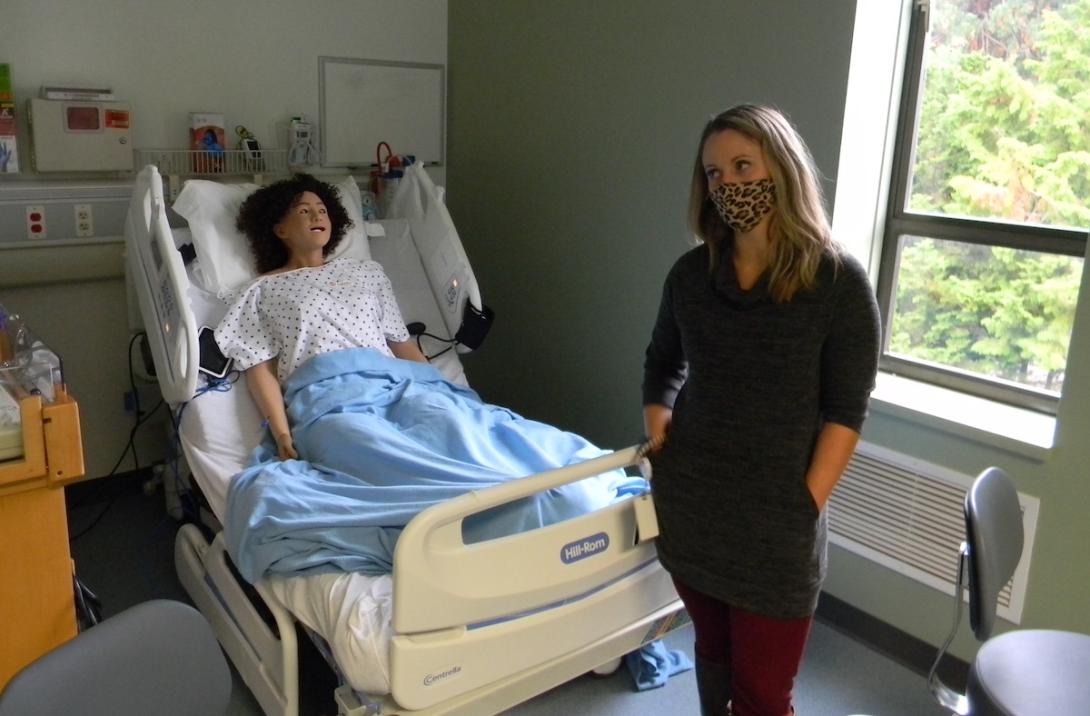

Early in the pandemic, the Oregon State Board of Nursing issued a temporary waiver allowing nursing programs to substitute more of students’ clinical experience with simulations. These created scenarios that can include paid actors (who play characters like “Xan Hawkes”) or specially outfitted manikins that require students to apply key nursing concepts while being observed remotely by instructors.

Kevin Mealy, spokesman for the Oregon Nurses Association, said that while nursing remains an “in-person profession,” technology has come a long way from the skeleton in your seventh-grade science classroom. He said more schools are adopting technology that replicates real-world hospital settings.

Research shows that simulation can, under the right circumstances, effectively replace clinical experience. But there are signs not everyone in Oregon’s medical community is sold on it, with some critics favoring real-life experience and others pointing to the varying degrees of quality among simulation programs.

Casey Shillam, dean of the University of Portland School of Nursing, said in an interview earlier this summer, that the pandemic has demonstrated how simulation can be effective. With changes to state regulations, she said there’s an opportunity to reshape the traditional model of nursing education.

“I think that this last year and a half has done a lot of things to our industry,” she said. “It’s like pulling back the curtain on systems and operations that have been dysfunctional for a long time. The pandemic has really shown that these systems and ways of doing things are not sustainable.”

Inside The Sim

With all the students back in the classroom, Newhall talked through the simulation.

“Can you not charge the person?” Newhall asked, referencing how West told Hawkes not to worry about the cost of the lost medicine.

The students discussed their possible options for a patient in that situation before Newhall suggests talking to the patient about ways they can advocate for themselves. The visit with Hawkes was good overall, said Newhall. But she asked if they had forgotten to check the patient’s lymph nodes.

“Darn it!” exclaimed West.

The University of Portland School of Nursing has been using simulation since 2007, said Shillam. In 2019, the school completed a large remodel of the Buckley Center building to expand simulation.

Stephanie Meyer, director of the university’s Simulated Health Center, explained that juniors and seniors enter simulation after completing nursing basics and other general requirements for their bachelor of science in nursing degrees.

The center includes six acute-care simulation suites, 17 acute-care patient beds, six primary care exam rooms. They all closely resemble medical settings.

Dixie cups, drug guides and boxes of blue medical gloves are stacked on cabinets. Dry-erase boards with calculations of drip rates are affixed to walls overlooking empty beds. And, high-fidelity “medical manikins” are stretched out in others. The manikins are equipped with speakers that instructors, observing from another room, can use to play a patient’s role and respond to students.

During simulations, instructors can make two baby manikins turn blue, cry or have seizures.

“We provide a great deal of respect for our manikins,” said Meyer. “We want our students to treat them like patients.”

Professional actors who’ve written backstories for reoccurring patients will lay in other beds during simulations, sometimes with life-like fake wounds complete with puss. Cabinets outside the medical bays are stocked with mock medications as well as saline flushes and hypodermic needles that can be injected into protective pads on actors.

Instructors observe simulations from multiple cameras that can zoom in to see if a pump is on the correct setting. Instructors can also raise a patient’s blood pressure if students aren’t responding correctly to their condition.

But Meyer said instructors are more interested in students’ clinical decision-making. In some simulations, students might pay more attention to a beeping IV pump over an actor playing a patient who is having trouble breathing, she said. Mistakes like these are teaching moments, she said.

These simulations aren’t just about checking off boxes, Meyer said. Students observe each other and talk through simulations to link nursing concepts to practice.

“We're trying to get behind their thinking,” she said.

Shillam said the university completed the expansion of its simulation facilities at just the right time.

Simulation During The Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic made it harder for nursing schools and other medical training programs to find clinical training placement for students.

A report released last year by the Oregon Center for Nursing described how many health care agencies closed to students out of concerns about personal protective equipment, risks of spreading the virus, workforce burden and other factors.

Even with a dire shortage of health care workers, Oregon Health & Science University over the summer reduced the size of its incoming physician, physician assistant and pediatric nurse practitioner classes. The reason for the cuts was the already inadequate number of clinical training spots being further reduced by clinics and hospitals suspending non-urgent procedures and adopting COVID-19 protocols.

Students seeking to become a practical nurse, a role that provides basic care for patients, must complete 360 hours of clinical practice. To become a licensed registered nurse, who administers medicine and treatment, it’s 720 hours.

Earlier in the pandemic, the Oregon State Board of Nursing adopted a waiver allowing nursing programs to substitute more clinical time with simulation, board spokesperson Barbara Holtry said. Students’ final practicum still needs to be done in a clinical setting, she said.

Last year, the board adopted permanent rules allowing nursing programs with certified simulation coordinators to replace up to 49% of the required clinical hours with approved simulation. Those without certified simulation coordinators could replace up to 20%.

Most nursing programs turned to simulation during the pandemic, according to the Oregon Center for Nursing report.

But the report, based on interviews with 17 facilities and schools across the Portland metro area, found mixed opinions among faculty. Some said simulated scenarios allowed students to focus on clinical decisions. Others said it was an inadequate substitute for real life.

Minutes from the Oregon State Board of Nursing show the transition to simulation wasn’t always smooth. Earlier this year, the board heard about hospitals concerned with onboarding new graduates who had simulation without clinical experience. Ruby Jason, the board’s executive director said in July that the “quality of simulation varies based upon available facilities and faculty,” according to minutes.

Nursing assistant programs seemed to have the most difficult time. Only half of programs using simulation had faculty trained on the technique, according to minutes.

“While solid evidence exists for the effectiveness of simulation, it is not known to what extent simulation can be used to offset clinical experience and still achieve learning outcomes at a comparable level,” the Oregon Center for Nursing report said.

Despite the difficulties, the report said several programs expect simulation to become permanent.

One of those is George Fox University’s College of Nursing. Pam Fifer, the college’s associate dean, said the college began investing in simulation about three years ago. The college recently completed a remodel adding nine new simulation beds and a skills lab, she said. About 40% of the program is simulation, more than other programs, she said.

Even before the pandemic, the high demand for nurses created bottle necks around clinical training, said Fifer. Nursing programs were producing new graduates and health care facilities had to balance orienting new hires with taking on students, she said.

In addition to medical manikins and professional actors, nursing simulations at George Fox include “hallway scenarios” that could include a disrespectful doctor or nurse who doesn’t wash their hands, she said.

“During COVID, our faculty has done more to create high-quality simulations that help students meet learning outcomes,” she said.

Other programs are taking a different approach. OHSU School of Nursing switched to virtual learning and the university relied more on simulation for its programs early in the pandemic. But now, the OHSU School of Nursing has mostly returned to its baseline for how much undergraduate students spend in clinical and simulations, university spokesperson Franny White said in an email.

As of the spring of 2021, OHSU undergraduate nursing students spent about 9% of their hands-on clinical hours, or 100 hours total during the course of their education, using high-fidelity simulations, she said. OHSU also used the pandemic to improve and expand how students are taught about telehealth, including using paid actors to portray patients during video calls or in-person visits, she said.

Does It Work?

Both Fifer and Shillam, dean of UP’s nursing school, said simulations can ensure that students are applying what they learn in classrooms. For example, students might learn about heart failure, but there’s no guarantee they’ll see it in a clinical setting, said Shillam.

Shillam said UP students are regularly assessed to make sure they’re learning. She said a challenge is the lack of research on what the minimal number of hours students should be in off-campus clinical environments.

The most comprehensive look at simulation in nursing education was a landmark 2015 study by the National Council State Boards of Nursing. The study tracked three groups of students: the first had regular clinical training, the second had 25% of clinical hours replaced with simulation and a third group had half of these hours replaced by simulation.

The study found no significant differences in clinical competency, knowledge or licensing examination pass rates among the three groups.

Nancy Spector, director of regulatory innovations for the National Council State Boards of Nursing, said all the programs included in the study started with at least 600 hours of clinical training and the simulations used were based on good methodology.

More nursing programs embraced simulation after the release of the study, she said. But the quality of simulation used by nursing programs over the pandemic varied, ranging from watching a video to augmented reality, she said.

She said a study on the pandemic’s impact on nursing education and outcomes that her group is conducting will focus on simulation.

Beverly Malone, president and CEO of the National League for Nursing, said that simulation will remain a part of nursing education. While simulation varies in quality, what’s important is that instructors be trained to link skills to concepts, she said.

“Skills can be learned, but do I understand why I’m doing it?” she said.

Kate Hamburg, a recently minted registered nurse and UP graduate, said simulation works.

She said it allowed her the space to talk through thought processes and ask questions. She said practicing difficult conversations with patients around suicide and mental health was particularly helpful.

“The hospital setting is so fast-paced you don’t get to sit down and ask, ‘why did we do the things we did with our patient?’” she said.

Jake Thomas can be found on Twitter at @JakeThomas2009.