Potentially lethal bacteria infected Oregonians at a higher rate while they received health care in 2021, state officials say.

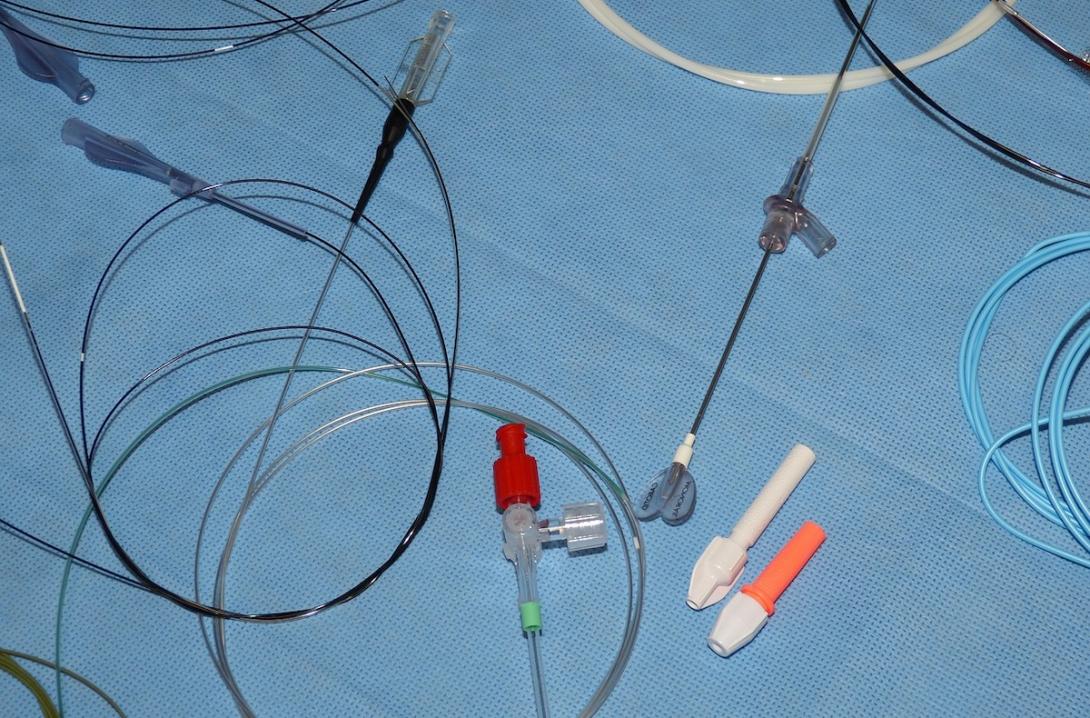

Newly published Oregon Health Authority data shows the rates of multiple types of infections jumped as the state’s health care system struggled with demands from the COVID pandemic. Infections contracted while receiving care for a different condition in a health care facility can be fatal and may be transmitted by a catheter, ventilator or a central line used to deliver blood or medication.

The Oregon data mirrors national trends and suggests providers struggled to follow safety protocols during the pandemic, according to information the state provided.

“OHA tracks and works to prevent these infections because they pose a significant risk to patient safety,” Rebecca Pierce, an authority program manager, said in a statement. “This is truly an issue that affects us all, as anyone receiving medical care could be at risk for a health care-associated infection.”

Hospital infections have been an ongoing challenge for providers before and after the pandemic. About 1 in every 31 hospital patients at any given time has an infection acquired in a health care setting, of which 1 in 10 may die while hospitalized, according to Pierce.

Oregon hospitals missed multiple national targets for preventing patients from becoming infected while receiving care. Two types of infections increased more than others, according to the health authority.

Health officials use a ratio, instead of the total number of infections, to gauge the problem. The ratio compares the number of recorded infections to those that were anticipated in order to take into account that some hospitals treat sicker patients.

Oregon’s acute care and critical access hospitals saw the largest infection ratio increases for catheter-associated urinary tract infections. They also saw an outsized increase in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections, which is caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The rest of the country saw similar increases in these infections, according to a study from researchers with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“In a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) ward in 2020, preventing a catheter-associated urinary tract infection was probably not always the foremost consideration for healthcare staff,” Dr. Tara Palmore and Dr. David Henderson, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Nurses and doctors were trying to save the lives of surges of critically ill infectious patients while juggling shortages of respirators and, at times, shortages of gowns, gloves, and disinfectant wipes as well.”

Even before the pandemic, Oregon hospitals were already not meeting national targets for surgery-related infections including coronary artery bypass grafts, hysterectomies, as well as hip and knee replacements. Hospitals saw their infection rates rise in 2021 for these procedures.

The Oregon Association of Hospitals & Health Systems as well as Providence Health & Services, the state’s largest health care system, did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Coming out of the pandemic, hospitals have complained they continue to be strained by labor shortages and a lack of beds in other facilities for patients who need lower levels of care. A recent report from Apprise Health Insights found that more than two-thirds of Oregon’s hospitals lost money in the first quarter of 2023, with some having to tap into reserves.

Matt Calzia, director of nursing practice and professional development for the Oregon Nurses Association, told The Lund Report he was disappointed that hospitals were backsliding on infections after making progress before the pandemic. He said hospitals are focused on their bottom lines instead of making investments that he said would improve patient safety.

“I think the pandemic just strained things so it made it worse, but hospitals have been trying to cut back on staffing. ... I think this is the result. You need people to be able to provide really high quality care.”

“I think the pandemic just strained things so it made it worse, but hospitals have been trying to cut back on staffing,” he said. “I think this is the result. You need people to be able to provide really high quality care.”

The association, the state’s largest nurses union, has argued that inadequate staffing has caused nurses to flee the profession. The union successfully lobbied for a new law setting minimum staffing levels at hospitals. Calzia said he expected the new law to make a difference in patient safety.

While Oregon’s health care infection rates followed national trends, hospitals did make progress in preventing a bacterium that inflames the colon called Clostridioides difficile, or C. diff. Peirce attributed the decline to a heightened focus on washing hands and other antiseptic measures that marked the pandemic.

Additionally, Oregon bucked national trends by seeing a decrease in the rate of central-line associated bloodstream infections, a potentially fatal complication that occurs when a catheter is improperly placed in a large vein in a patient. However, the health authority noted in its press release that despite the decrease in the rate of these infections, acute care hospitals are not meeting the national target.