Calls to 911 reporting an overdose in Multnomah County jumped significantly in May and June of this year, doubling the number of calls made during those months a year ago, according to data obtained by The Lund Report.

The numbers are part of a larger data set showing nearly 7,000 calls reporting overdose over an 18-month period between January 2022 and June. The volume and geographic spread of the calls are significant because they illustrate the extent of suffering among people struggling with addiction in the Portland area. It also shows the strain that substance use disorder is placing on the local health system — a strain that paramedics say is growing.

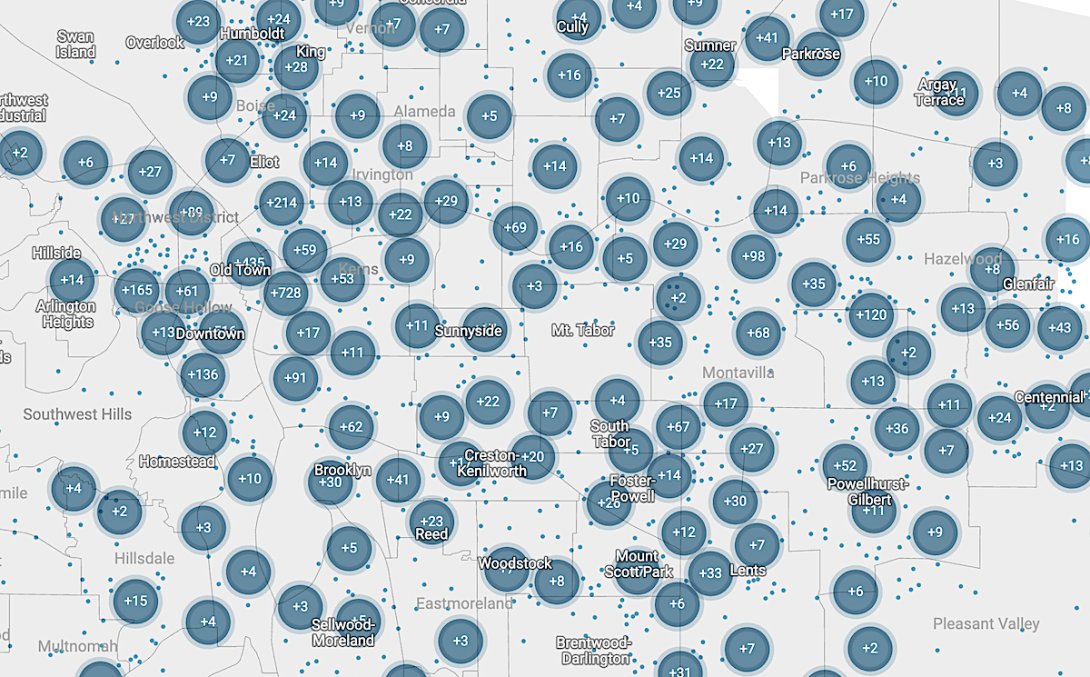

View a full screen version of the map here.

Notes about this data: Dots on this map represent calls made to 911 coded as “overdose.” These data points represent calls where first responders arrived on the scene, with canceled and duplicate reports removed. Not every overdose is reported as an overdose. Likewise, not every report of an overdose is an overdose. Due to the way the Portland Bureau of Emergency Communications triages calls, this data includes all forms of excessive intake of potentially harmful substances. We removed all calls coded as “poisoning” or requiring “poison control,” but it’s possible some poisonings and other non-drug overdose calls remain in the dataset.

The recent spike in overdose calls comes as different policy responses are being floated publicly, ranging from a crackdown on tent camping and an abandoned effort to ban public drug use from the mayor’s office to the county’s consideration of designating sites for safer drug use and a plan to distribute tinfoil and straws — a plan that was put on hold after public and political outcry.

While the newly released data comes with limitations, it illustrates how pervasive overdoses are across the Portland area, and it also shows how the calls tend to group in certain locations.

While news reports often focus on overdose deaths, most overdoses are nonfatal, and they come at a cost that’s rarely discussed. An overdose can cut off oxygen to the brain, causing lasting and serious health implications for those who suffer them. Meanwhile, because most overdose calls involve an ambulance and fire bureau response — and police if they’re available — they come at a cost to taxpayers and contribute to burnout among first responders.

“We definitely have seen an uptick in the number of overdoses on the street,” said Timothy Mollman, a longtime paramedic in Multnomah County.

“It wears on you, after a while,” Mollman said. “You’re just running these things over and over and over and you kind of feel helpless to be able to do anything in the long term about it.”

He told The Lund Report it’s not uncommon to respond to three or four overdoses during a single 12-hour shift. And he’s just one of many paramedics on the clock. At any given time, there are between 10 and 32 ambulances on duty across Multnomah County.

Mollman has treated the same person for two overdoses on the same day — and he said he hears similar stories from other first responders.

Typically, he said, a 911 dispatcher walks the caller through CPR until a medic arrives to administer naloxone. Once the person is revived, paramedics attempt to take them to a hospital for observation — but about a third of the time, he said, the patient declines.

“There’s no follow-up,” Mollman said. He and some medics have taken it on themselves to carry fliers and other information about the county health clinics and drug treatment resources to give to people who have overdosed. “There really isn’t an official program in place” to share those resources, he said.

Austin DePaolo, a Teamsters Local 223 official who represents paramedics in Portland, said overdose response is contributing to an increase in calls for local ambulances — which have recently come under fire for delayed response times.

“Our folks are getting burned out,” DePaolo said. More calls mean more overtime and less quality time at home with their families, he added.

Places with Numerous overdose calls

The following is a selection of places in Multnomah County that had a high number of dispatches to reports of overdose from Jan. 1, 2022 through June 25, 2023. This is not a complete list.

All TriMet Transit Stations: 222

Gateway Transit Station: 26

Skidmore Fountain & Transit Station: 18

Bud Clark Commons: 34

Blackburn Center: 32

Do Good Multnomah Shelter: 23

Portland Rescue Mission: 23

Pioneer Courthouse Square: 14

Businesses with highest numbers

McDonalds on Burnside: 13

Stadium Fred Meyer: 15

Chevron on Burnside: 18

Pete’s Market on SW 4th Ave.: 18

Jails

Inverness Jail: 7

Multnomah County Detention Center: 7

Street corners with numerous overdoses

SW 4th Ave. & Washington St.: 23

SW 5th Ave. & Harvey Milk St.: 18

SW 5th Ave. & Oak: 19

The Lund Report’s analysis of 911 call data shows that while many calls reporting overdoses are concentrated in areas that Portlanders might expect — such as Old Town and around downtown’s ever-shifting fentanyl market — reported overdoses also reach into nearly every residential neighborhood to some extent, including the Southwest Hills.

Mollman said that while people who know they are using opioids usually aren’t surprised when they overdose, those who thought they were taking something else are often caught off-guard. Recently, he said, paramedics have been saving what seems like a lot of people who overdosed on fentanyl that they thought was cocaine.

He said that was the case with a recent response involving three people. “They got off work, they went out, got a couple beers. They thought they had a bag of cocaine in their hands ... and all three of them ended up overdosing. Luckily, they were in a public area, and so it was caught, and none of them died on that one,” he said.

Dr. Teresa Everson, the county’s interim health officer, reported to county commissioners on June 27 that the medical examiner has confirmed 334 overdose deaths in Multnomah County last year, a number that will go up as the office works through its caseload. In 2021, there were 360 overdose deaths — a sharp increase over the three years prior, which is in line with national trends. Overdose deaths from synthetic opioids have gone up 533% since 2018 in the county.

Many retailers, motels, shelters and transitional housing complexes in Multnomah County were the subject of 5 or more calls to 911 for reported overdoses during the past 18 months. Bud Clark Commons, an apartment complex run by the city of Portland, saw the highest number of calls — 34.

Roughly half of the 7,000 calls indicated overdoses occurred on business premises or in parks, along roadways and in other public spaces. Mollman said these calls typically involve people experiencing homelessness.

Many overdoses reversed when bystanders use naloxone

Haven Wheelock runs the nonprofit Outside In’s harm reduction services, which promotes safer drug use such as with clean syringes. She said 35% of her clientele reported experiencing an overdose during the past year. That’s up from 27% in 2019.

Wheelock, who carries the opioid reversing drug naloxone both on and off the clock, said she’s personally reversed 48 overdoses over the past decade.

In just the last couple of years, she’s reversed four overdoses outside of work in public spaces.

There was the time at a bar in Southeast Portland, once in a parking garage, once at a bus stop, and once when she went to a Safeway to shop.

“I was going to get my groceries, and I noticed something was wrong in the car I parked next to,” she said. She reversed the overdose with naloxone — and the person survived, though Wheelock was left “a little rattled.”

Wheelock said she always calls 911 when she reverses an overdose. Her call from the Safeway parking lot a few months ago was just one of 30 such calls made from area Safeway stores since the start of 2022.

Many major retailers operating in the Portland area have seen a high rate of these calls from their premises. For example there were 54 calls made at Fred Meyer stores and 27 at area Targets.

Mollman said roughly half the time he shows up to an overdose call, a bystander has already reversed the overdose with naloxone. These calls aren’t necessarily recorded as confirmed overdoses, which makes it harder to obtain concrete data. There are also a lot of overdoses that get reversed but are not reported, as well as overdoses that are called in as something else.

But the volume of overdose calls to public spaces — about 2,000 last year, according to county officials — is in line with anecdotal reports.

Public drug use: No consensus on solutions

In response to widespread public drug use and the area’s surging rate of overdoses, the city and county have offered solutions from opposite ends of the spectrum — but neither have stuck.

Signs of an overdose

According to experts interviewed for this story, these are signs that a person may be experiencing an overdose. If you suspect an overdose may have occurred, call 911 immediately.

Lying on the ground in an unnatural way — look to see if they are using anything as a makeshift pillow. Are they in a doorway with a backpack under their head, as if to take a nap, or are they lying haphazardly in the middle of the sidewalk?

Listen to their breathing. Before they lose oxygen, their breathing may sound gurgling, or like snoring. Are they breathing effectively?

Lips and fingertips appear purple, pale blue or ashy gray — these are signs the person is no longer getting oxygen

Vomit — some people vomit as the overdose begins

Unconscious — can you wake them up?

Be prepared

Carry naloxone with you in cases of emergency, and learn how to administer it. Anyone can obtain the drug from from a local pharmacy. Most insurance will cover the cost of naloxone for those at risk of overdose. GoodRx offers discount coupons for those paying out-of-pocket for naloxone. On Friday, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a second naloxone nasal spray product for over-the-counter sales — at least one of the two products is expected to be available later this summer. For those who use opioids, naloxone and fentanyl testing strips are available for free from syringe service programs, such those run by Multnomah County and Outside In.

Get trained in CPR — some overdoses can be reversed with CPR alone

What to do

Ask the person if they are OK, attempt to wake them

If they are not OK, call 911

Administer naloxone if it’s an emergency

Stay with the person, try to keep them awake and remind them to breathe

If the person is not breathing, chest compressions and rescue breaths from a trained individual could save their life. Chest compressions alone are better than nothing if you’re not comfortable giving rescue breaths until paramedics arrive.

In June, Mayor Ted Wheeler proposed banning public drug use. The plan was dropped over concerns about the legality of his proposal, but advocates and health officials had other fears. For one, more people would be prompted to use drugs out of sight to avoid criminal charges, increasing the likelihood of an overdose death.

“If they’re using in a semi-private space, then they’re less likely to be observed if there’s an overdose, and they’re less likely to get a response,” Everson, the county’s health officer, told The Lund Report before news of the proposal’s withdrawal was made public.

Additional arrests for drug use could also have the unintended consequence of driving overdose rates up further. Everson said that’s because “there’s actually a pretty big risk of overdose when you restart use after any period of time not using it with fentanyl.”

Meanwhile, Multnomah County’s health department took an approach intended to reduce the harm of drug use. Earlier this year, it made plans to distribute tinfoil and straws to people who smoke fentanyl as a way to engage them with services, but after the plan drew criticism, the county suspended it.

One idea still under consideration is “overdose prevention sites.” Formerly known as safe injection sites, these are places where people can safely use pre-obtained drugs in the presence of medical staff trained in overdose prevention and reversal. Studies have indicated these sites significantly reduce deaths from overdose, increase drug-treatment enrollment and decrease rates of public drug use.

“I’ve been having conversations for the last year about, what do we do about public use?” Wheelock told The Lund Report. “And overdose prevention sites are the most obvious one.”

The increase in public drug use and overdoses in public spaces has recently “revived” conversations among county officials about the possibility of such sites, Everson, said. But it’s just one option under consideration and discussions are still preliminary, she added.

Responding to an overdose quickly can not only make the difference between life and death, but also the difference between a full recovery and brain damage. Mollman said paramedics have regular contact with some people in Portland who, due to long-term health complications from overdosing, “require almost 100% care for the rest of their life because of these brain injuries.”

The most extreme cases are patients who are on long-term ventilation, he said, “they can’t function on their own, they can’t breathe on their own.”

Fentanyl sends people into overdose and oxygen loss much quicker than heroin. Everson said the cognitive effects of overdose can affect job performance and relationships and can include difficulty processing information, impaired memory, depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts.

How frequently overdose leads to long-term cognitive impacts isn’t clear. Due to the stigma around drug use, people may not seek help, Everson said. And for people who are still using, long-term cognitive impacts can be difficult to untangle from the effects of the drugs they’re taking.

Everson pointed to a 2019 study that found 5.5% of people admitted to an emergency department for a nonfatal opioid overdose died within one year of that visit.

One of the biggest concerns about nonfatal overdoses, she said, is that they tend to lead to fatal ones.