A law designed to make the interpreter industry more equitable and inclusive has one group saying state officials are excluding them unfairly.

And the group hasn’t been able to get an audience with officials to talk about it.

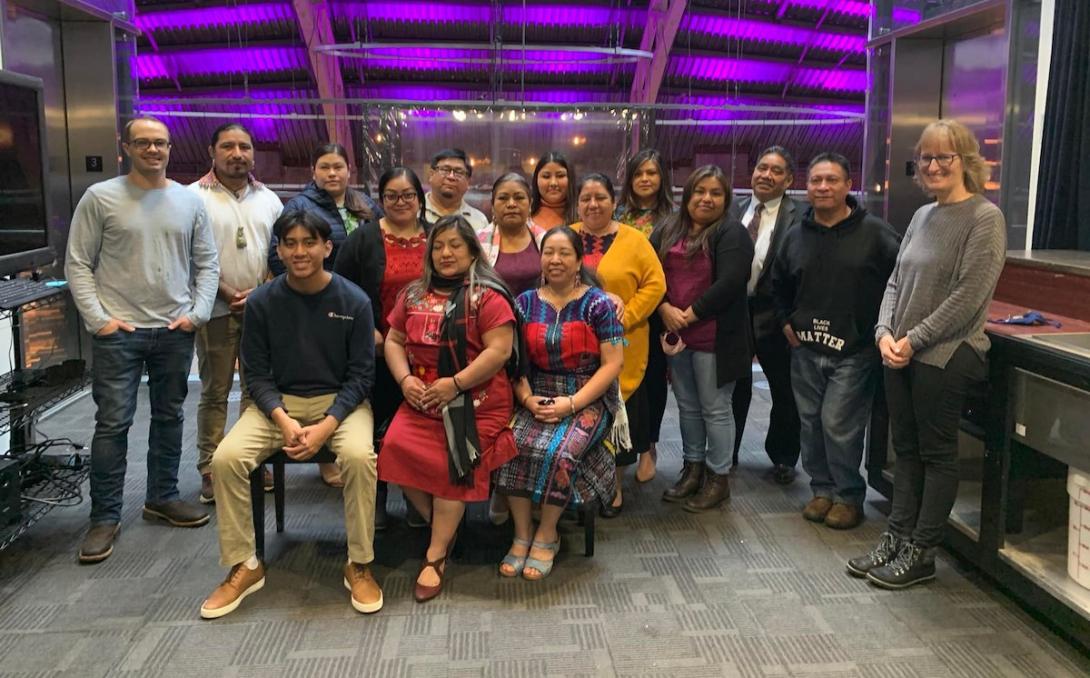

For more than a year, records show that Cameron Coval tried unsuccessfully to set up a meeting with staff at the Oregon Health Authority on behalf of Indigenous language interpreters. The 15-member group he represents, called the Collective of Indigenous Interpreters of Oregon, is seeking a pathway for its members to become certified to work in health care settings. So far, the agency’s Office of Equity and Inclusion — which oversees the health care interpreter program — has ignored the groups’ repeated requests to meet and be involved in policy-making discussions around rules governing their profession.

Most members of the collective interpret Native languages spoken among an increasing number of immigrant communities hailing from Mexico and Guatemala. These languages include Mayan languages such as Kʼicheʼ, which is spoken by more than one million people in Guatemala, and Mixtec, a language with multiple variations spoken by more than a half million Mexicans.

Coval is the co-founder and executive director of an immigrant advocacy and legal services nonprofit called Pueblo Unido, which supports and facilitates the Collective of Indigenous Interpreters of Oregon. He told The Lund Report many of the state’s requirements act as barriers to Indigenous language interpreters becoming certified with the state, and until recently, one requirement couldn’t be met by any of the interpreters in the collective he represents: proof of proficiency in the language they’re interpreting.

“There are no language proficiency testing options available for Indigenous languages,” he said.

On Dec. 6, Oregon Health Authority made available an alternate pathway for meeting this requirement when no proficiency test is available. That requirement can now be met by following instructions on a form that include submitting a letter with references who “are familiar with your proficiency” and other information for approval on a case-by-case basis.

Coval said that on the national level, “some in the industry have concerns about relying on recommendations from other individuals who purport to be proficient in languages of lesser diffusion, but who have not been determined to be proficient themselves.” He said it’s an issue of “who rated the rater?” Instead, he said the state should learn from programs such as the National Institute of Indigenous Languages in Mexico, which in the past had a practical system for cultivating and assessing potential proficiency raters.

Other certification requirements act as additional barriers, such as submitting to a background check, also meeting English language proficiency standards, and having a high school diploma or equivalent, he said. Indigenous language interpreters are typically immigrants who may not have had access to high school education in their country of origin. They may be wary of background checks due to immigration status, and often Spanish, not English, is their secondary language. In these cases, they work with “relay” interpreters: They interpret from the patient’s Indigenous language to Spanish, and then the relay interpreter translates their Spanish to English for the health care provider.

But the 60-hour class required for certification in Oregon is offered only in English, and certification also requires proof of English proficiency.

Fed up with what Coval describes as the Oregon Health Authority’s refusal to engage with the group, about a dozen Indigenous language interpreters submitted testimony during a public hearing last week to get their message across.

‘I Also Am A Professional’

The purpose of the hearing was to gather public comment on a set of proposed rules that would mandate health care providers hire only interpreters listed on the state’s registry of certified interpreters when communicating with patients whose preferred language is not English.

While many health care interpreters are already certified and on the state registry in Oregon, there is no enforced mandate requiring providers to hire interpreters from the list. The proposed rules would change that by strengthening existing laws.

A clause written into the proposed rules, however, would allow the hiring of non-certified interpreters — but only when “good faith” efforts to hire from the list are exhausted. But Indigenous language interpreters say the restrictions on certification further marginalize their community — going against the equity-focused spirit of the law.

The rules, spurred by the passage of House Bill 2359 last year, are intended to create accountability to patients and bring equity to an industry plagued by, according to the text of the bill, “inequitable business practices of interpretation service companies.”

The proposed rules would eliminate the $25 fee to be listed on the state registry, in hopes of making registration easier for members of marginalized groups. They are also intended to stop providers from using companies that offer lower-paid, uncertified interpreters as a cost saving measure.

Health authority spokesperson Jonathan Modie initially told The Lund Report in an email that Indigenous language interpreters could meet the language proficiency requirement outside a testing center by having an organization or community that represents them provide that testing for languages that do not have a test available.

But no entities are providing such a service, placing the onus on Indigenous interpreters to implement their own complex testing systems in order to comply with the law.

Later on, after an initial version of this article published, Modie sent a copy of the new state form addressing the same concern. While available on the state website, this alternative pathway is not referenced specifically in the proposed rules, on the list of requirements, or on the certification application, and many interpreters remain unaware of its existence.

Puma Tzoc, coordinator of the Collective of Indigenous Interpreters of Oregon and a Mayan K’iche’ interpreter, explained how challenging the certification barrier was in his testimony.

“In Guatemala, we have 24 Indigenous languages, in which each Indigenous language has their own variations,” he said, noting that four members of the collective speak three different variations of K’iche’.

“If OHA is to rely on community organizations to provide language proficiency testing for languages that do not currently have a test available,” Coval said of the longtime barrier, “it is incumbent on the state to make an investment in such efforts.”

Oregon Health Authority officials acknowledged in the text of the proposed rules that there “is some concern about the impact of the rules on access to interpreters where languages are only spoken by individuals in small numbers or closed communities. However, improving access to certified or qualified healthcare interpreters is designed to create better health outcomes and reduce health disparities for those with limited-English proficiency, an outcome that increases racial equity.”

In its written testimony, the Collective of Indigenous Interpreters of Oregon and Pueblo Unido countered that: “In essence, the Authority is stating that improving language access for some groups justifies the further marginalization and limitation of language access for other groups. This logic is not merely flawed, it can have life or death consequences for speakers of those marginalized languages.”

Coval told The Lund Report that the demand in Oregon for Indigenous language interpreters is “huge, and it’s growing.”

He said there’s been increased migration of Indigenous people from Guatemala and Mexico over the past five years, driven in part by climate change and other factors, such as insecurity, lack of opportunity and the discriminatory structures in those countries that make living there difficult for people from Indigenous communities.

The text of H.B. 2359 recognizes this trend, pointing to “a growing demand for health care interpreters in rural communities in this state, especially for interpreters capable of interpreting languages of limited diffusion in those areas” as reason for passage of the act.

Coval said “languages of limited diffusion” is an “umbrella term for a lot of languages, but a large component of that are Indigenous languages from Mexico, Guatemala.”

Testimony during the March 21 hearing touched on other concerns the public has with the proposed rules, with comments made both in favor and against the inclusion of remote interpreters in the new requirements.

Some interpreter industry representatives said remote workers from out of state, who often offer language services otherwise unavailable in Oregon, would just choose not to work in the state.

“I do think that interpreters who don’t want to get certified will avoid working in Oregon,” Rep. Andrea Salinas, D-Lake Oswego and sponsor of the bill, told The Lund Report, “but the idea is to professionalize the service and as such increase worker pay. I imagine higher pay could actually attract remote interpreters to Oregon’s certification and registry process.”

Several other public commenters made requests for robust enforcement mechanisms and a better complaint process to ensure accountability.

But several who commented and submitted testimony about these and other areas noted their support of finding solutions to Indigenous interpreters’ concerns.

“It just does not seem that the Indigenous interpreters were ever consulted about the implementation or creation of the bill, and certainly weren’t considered in how these proposed rules will affect them,” Coval told The Lund Report.

Salinas confirmed that in the drafting of the bill, Indigenous language interpreters were not “specifically’ reached out to. She said the Oregon Health Care Interpreters Association, however, assisted in the bill’s creation.

In addition to background checks and education requirements, there are other certification requirements that continue to pose barriers to interpreters.

The Indigenous interpreter collective also testified that the required 60-hour training for certification should be offered in Spanish and that Spanish proficiency should also be considered.

Through a Spanish-to-English relay interpreter, Maya K’iche’ interpreter Romeo Sosa said during the public hearing that “what you’re doing with this proposal is a way to exclude us again, and also a way to humiliate us again.”

Guatemalan language interpreter Domingo Martinez echoed this sentiment: “I also am a professional,” he said through a relay interpreter.

Because so few are able to interpret for the Maya Mam community, said Bertilda Martin Mendoza in written testimony, relay interpreters must be used. There are not enough certified and qualified Mam interpreters to meet the demand, she said.

While the public comment period closed after the hearing, spokesperson Modie told The Lund Report that Oregon Health Authority is now accepting written public comment until April 15. The agency plans to finalize and publish the proposed rules April 29, he said, and they will go into effect July 1.

Shut Out Of The Process

In January 2021, before the agency was poised to strengthen mandates around certification for health care interpreters in Oregon, Coval reached out to the Oregon Health Authority to express concerns about the certification process.

In an email, he told Edna Nyamu, who is a program coordinator and oversees the Health Care Interpreter Program with the agency’s Office of Equity and Inclusion, that “many of the requirements for the program are arbitrary and unattainable for most indigenous interpreters, including those with prior formal training and over a decade of experience.”

He also told Nyamu that after he and a group of Indigenous language interpreters met with the Oregon Health Care Interpreters Association to find out more about becoming certified, they learned requirements imposed by the agency’s Office of Equity and Inclusion made certification unattainable.

Coval debriefed the interpreters after the meeting, “and each member expressed frustration and a feeling of exclusion with the requirements imposed by OHA's Office of Equity and Inclusion. The irony was not lost on them, as they suggested the office should be renamed, the OHA Office of Exclusion,” his email stated.

In the same email, he requested a meeting.

He told Nyamu that he wanted to discuss the barriers to certification, as well as a comprehensive training program for Indigenous interpreters that the nonprofit he oversees, Pueblo Unido, was at the time developing.

“Pueblo Unido intends to cover the cost of this training program and otherwise eliminate as many barriers to participation as possible for members of the Collective of Indigenous Interpreters of Oregon,” he wrote. “Upon successful completion of the 21-module training curriculum, we hope that OHA will recognize the interpreters as competent and accredited.”

He received no response for six months.

Finally, in July, he said Nyamu called him in response to the email, which he had sent in January, and asked that he send potential meeting dates.

As evidenced in emails shared with The Lund Report, Coval repeatedly attempted to set up such a meeting, but the exchanges went nowhere.

His last attempt was made this past August, and he said he has still not received any reply.

The training program Coval referenced in his emails incorporates many of the health care topics required by the health authority, and has since become operational, seeing its first class of graduates in December. But it has been unable to incorporate an extensive review of medical terminology because the health authority’s collaboration is needed. There are “no direct translations for medical-ese or legal-ese in Indigenous languages,” he said. He had hoped to flush out a plan with the agency for meeting its requirements in that area, but “those efforts have been rebuffed thus far,” he said.

Coval, along with another member of the collective, also made a request this past December to join Oregon Health Authority’s Rules Advisory Committee on H.B. 2359. He sent that request to the equity and policy manager at the agency’s Office of Equity and Inclusion, but said he never got a reply.

“(She) did, however, find time to reply to others who expressed interest in joining the RAC,” Coval said. He shared that reply to another interested party with The Lund Report.

Health authority spokesperson Modie acknowledged “there was not a self-identified speaker of an indigenous language on the Rules Advisory Committee,” but said his agency “will look for such representatives for future rulemaking as it moves forward to address these issues.”

Oregon Health Authority did not address a question about why it wouldn’t meet with the Indigenous interpreter collective in its response to The Lund Report’s inquiry. However, Modie stated that the agency “appreciates the testimony received at the public hearing from speakers of indigenous languages and is looking forward to talking in further detail with representatives of the Collective of Indigenous Interpreters of Oregon, to discuss how it might be able to address their concerns.”

But last week, after more than a year of failed attempts to have that conversation — Coval and 12 members of the collective felt they had no other option than to show up virtually to submit comment.

Coval said they would have preferred to meet with the health authority “face to face.”

Submitting testimony is not the same, he said. “That's not a conversation. That's a one-way statement.

“We offered to work with the state to come up with potential solutions for offering language proficiency testing for Indigenous languages and their variations, but the state must accept that offer for collaboration in good faith,” he said.

Coval said the ability to work through an exception carved out in the rules for non-certified interpreters isn’t enough to satisfy the Indigenous language interpreters he represents — there’s also the “matter of principle.”

Members of the collective feel that the barriers to certification they’ve long faced — only some of which are just starting to be addressed — amount to “just blatant racism,” he said.

“And that’s exclusivity. And that’s further marginalization of Indigenous communities. And I don't think that’s the message that OHA or the state intend to send. But that is the message that was received by Indigenous interpreters by these rules.”

To learn more about the proposed rules, visit this page at the Office of Equity and Inclusion’s website. Submit public comment to this email address.

Correction: In the initial version of this article, it was stated there was no way for Indigenous language interpreters to meet language proficiency requirements for many Indigenous languages. We have since been made aware of a work-around that was implemented in December. The Lund Report regrets the error.

You can reach Emily Green at [email protected] or via Twitter at @GreenWrites.