Last month, state health officials announced “encouraging” results in the yearly report card showing how publicly funded insurers performed in delivering care to more than 1 million low-income Oregonians.

But a deeper look at the underlying numbers by The Lund Report shows that delivery of care to members of the Oregon Health Plan took a major step backward during the pandemic:

- Despite some gains in 2021, the Medicaid-funded system continued to lag behind its pre-pandemic performance in areas that include diabetes management, dental checkups for children and depression screenings.

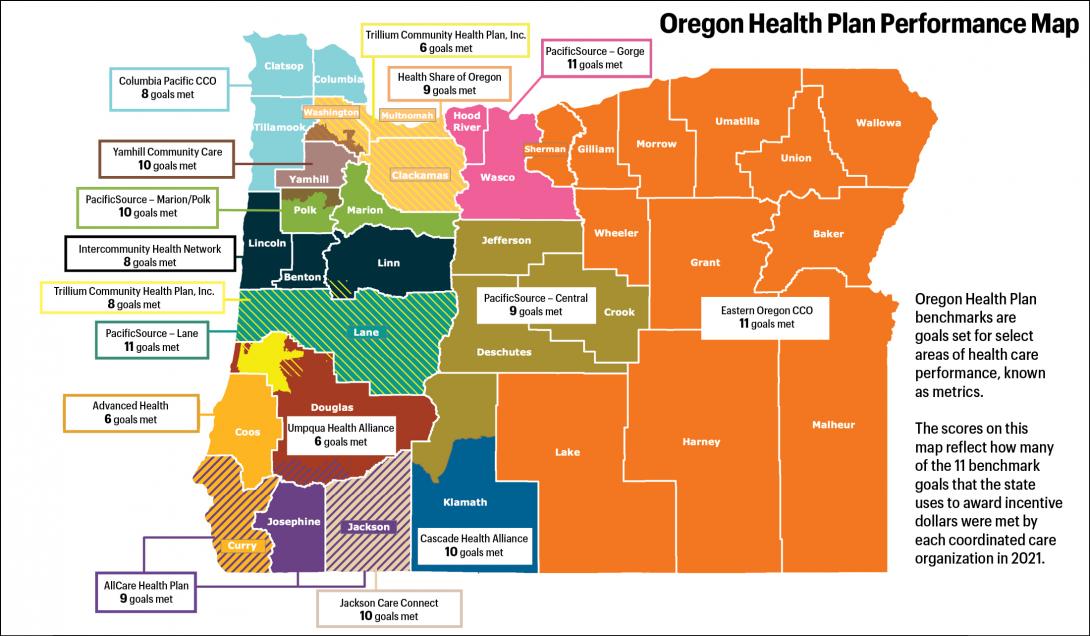

- The numbers, known as metrics, showed major variations in how well the state-authorized regional insurers in the plan reached and served their members last year.

- A state committee composed of insurance representatives and providers last fall reduced goals for the metrics, even as burgeoning enrollment in the low-income plan increased the incentive payouts. The state used the benchmarks to allocate $266 million in incentive awards to the plan’s 16 regional insurers. That’s $100 million more than the state paid out to reward improved performance in 2019.

In all, the Oregon Health Authority last year paid out $6.26 billion to the regional insurers, known as coordinated care organizations, or CCOs, to deliver care.

Health officials say the system of metrics had to adapt to changes in patient behavior, COVID-19 restrictions, and severe shortages of personnel across the system.

“We’ve never had anything like this in the history of our country,” Stacey Schubert, director of health analytics for the Oregon Health Authority, told The Lund Report.

Improvements Were Interrupted

The yearly metrics report gives the public a snapshot of how each coordinated care organization is serving members in areas like immunizations, prenatal care and substance use disorder treatment.

The metrics are intended to ensure that the Oregon Health Plan’s regional insurers are continually improving as envisioned under nationally touted reforms the state instituted in 2012.

But then the pandemic hit. People often put off health care and sheltered in place to avoid catching COVID-19. The crisis exacerbated health care staffing shortages as workers retired or left due to stress and providers struggled to fill positions.

So the health authority suspended the metrics benchmarks, or goals for individual CCOs, and simply distributed $210 million that had been slated to reward improvements, to help insurers respond to the crisis.

For 2021, the committee set benchmarks, but reduced many of them.

Schubert said the decision was appropriate: “I think the metrics and scoring committee did the best job they could to balance all of the different considerations when setting the benchmark.”

Dr. Amit Shah, a former chair of the committee who stepped down earlier this year, serves as chief medical officer for coordinated care organizations serving people in Jackson, Tillamook, Columbia and Clatsop counties, called Jackson Care Connect and Columbia Pacific CCO.

“The system never faced something like this pandemic,” he said. “And when you look at all the measures that were achieved and all the care that was delivered, that’s an incredibly positive and important message that our communities and our society needs to hear because we always hear about all the bad stuff.”

At the same time, he said, metrics are a useful roadmap for improvement, and those that aren’t met – regardless of whether benchmarks changed – deserve a “deeper discussion.”

Reduced Standards Helped Insurers Meet State Goals

The pandemic affected Oregon Health Plan insurers’ ability to meet the state’s benchmarks because they made different decisions about spending.

It also affected the metric benchmarks by boosting the number of members in the program — the denominator on which the metrics are based. With Medicaid eligibility checks suspended, Oregon Health Plan enrollment grew from 1.1 million to 1.4 million.

“Some clinics are outperforming last year’s numbers, but with denominators increasing so sharply, the rates give the appearance they are behind,” wrote Donna Mills, executive director of the Central Oregon Health Council, in comments to the metrics committee last fall.

Based on such pleas, the metrics committee reduced the benchmark goals for seven of the system’s metrics last year.

The measure of how well insurers keep diabetes in check shows how this played out. The metric tracks the percentage of diabetes patients that year who either don’t get their blood sugar tested or have poorly controlled blood sugar levels.

In 2019, a regional insurer could meet the benchmark with a rate of 21.7% or less. If the state had kept that benchmark in place, only one of the health plan’s 16 care organizations would have met it last year: PacificSource – Lane County.

For 2021, however, the diabetes care benchmark was relaxed to 33.3% or less. As a result, 13 CCOs qualified and only three CCOs failed to hit that new benchmark.

Shah, the CareOregon chief medical officer and former state metrics chair, stressed that meeting a benchmark and quality of care “aren’t necessarily the same thing.”

For many metrics, the rates depend in part upon a person showing up at a provider’s office for treatment, he said. That explains why pediatric immunizations were an area of struggle for many CCOs.

“But if you think about it, a lot of families during the pandemic didn’t want to bring their kid in,” he said. “They were worried about risks.”

Shah said his organization has had instances of missing a metric by a fraction of a member.

“Does that mean that quality of care is lower than another organization that met this metric?” he said. “No. Does it mean that we didn’t receive quality pool dollars to reinvest in our community for that metric? Yes.”

Partial Bounceback, But Still Behind

A look at Oregon Health Plan metrics in recent years shows how the pandemic set the overall system back in numerous performance measures:

- The statewide portion of OHP members 12 and older who received appropriate screening and follow-up for depression plummeted from 60.4% in 2019 to 52% in 2020, holding steady in 2021.

- The portion of members with diabetes who are not properly managing it grew from 21.5% to 29% in 2020, improving to 27% in 2021.

- The portion of adolescents who received key immunizations dropped from 36% to 33.5% in 2021.

- The portion of members engaged in substance abuse treatment dropped from 17% to 16.2% in 2020 and to 15.4% last year.

- The portion of adults with diabetes who received at least one dental check-up annually plummeted from 30.7% to 20.3% in 2020, then climbed to 24.7%.

- The portion of children ages 1 to 5 that received annual dental checkups dropped from 51.2% to 37.5% in 2020. It rebounded to 47.2% in 2021.

- Screening and intervention with adult members with substance abuse conditions dropped from 62.8% to 50.2% in 2020, before climbing to 55.2% in 2021.

- The portion of adult members who received interventions or referrals to treatment after screening positive for unhealthy alcohol or drug use plummeted from 42.8 % to 29.2% in 2020, then fell again last year to 28.2%.

- The rate of children age 3 to 6 who have a wellness checkup dropped from 68.6% to 59.2%, before increasing to 64.1% last year.

There were also bright spots. The prevalence of cigarette smoking among members 13 and older continued to decrease. The rate of women who visited their doctor within 84 days after delivering a baby grew. Meanwhile, the portion of members who received drug and alcohol abuse treatment within 14 days of diagnosis held steady at about 39%.

The rate of patients with a history of mental illness turning to emergency departments for care decreased in 2020 and 2021, but the state metrics report noted it’s unclear what that means — as overall emergency room visits dropped as well.

Health Care Results Mixed For Counties, Regions

The state’s metrics report card showed major variations in how well the regional insurers in the Oregon Health Plan reached and served their members last year.

Three regional insurers met the state’s benchmark goals in only six of the 11 metrics: Advanced Health, which serves Coos County; Umpqua Health Alliance, serving Douglas County; and Trillium North, which recently began serving Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington counties.

Officials for the three organizations did not respond to requests for comment.

Health Share of Oregon, which serves a much larger group of members in the tri-county Portland region, hit the state’s benchmark goals in every area except two.

PacificSource - Gorge, which serves the Columbia River Gorge region, met the benchmarks in all areas. It also scored the highest in eight of the metrics, including health screenings for children and childhood immunizations, among others. PacificSource - Lane also met all 11 benchmarks.

Erin Fair Taylor, vice president of Medicaid programs for PacificSource, credited the advisory panels it uses to respond to community needs using input from hospitals, specialists, primary care providers, behavioral health providers and community organizations.

“Sometimes it means investing money,” Fair Taylor said in an interview. “Sometimes it might be hiring some additional positions. Sometimes it might be about education or technical assistance. It might mean making phone calls to members to get them in for care. There’s not a one-size-fits-all response.”

Eastern Oregon Coordinated Care Organization, covering a huge swathe of rural Oregon, met all of the state’s targets. Its CEO, Sean Jessup, credited outreach efforts that included vaccine hesitancy, education about well-child visits, resources for new parents and a diabetes self-management program.

In an email, Jessup said staffing shortages continue to be a problem, but “EOCCO will continue to work closely with its partners to address these barriers and work towards achieving its quality measure targets for 2022.”

Yamhill Community Care, which covers all of Yamhill County as well as portions of Washington and Polk counties, succeeded in all of the state’s measures except childhood immunizations.

Jenna Harms, its health plan operations director, said in a statement that the pandemic had significant effects, but “We continually work with our providers to support ongoing process improvement which is a center point for our success over the years.”

Cascade Health Alliance, which serves Klamath County, met 10 of 11 benchmarks. Dr. David Shute, chief medical officer, said the group’s long-term strategy of strong partnerships with providers and flexibility was key.

The pandemic didn’t just affect providers, it was “difficult and disruptive for all of our members as well,” he said. “And they’re part of success on these quality metrics.”

Officials say restoring the benchmark goals to pre-pandemic levels will be a “multi-year” process.

Maribeth Guarino, a consumer advocate who tracks health care for OSPIRG, told The Lund Report that getting that system back in place is important.

“Of course the pandemic required a lot of changes from everyone in the health care system, from insurance carriers to delivery systems, and will have some long-term effects, but that doesn’t mean we can’t be ambitious in getting back to some semblance of normal,” she said. “Post-pandemic, high-quality care is more important than ever, and the CCO benchmark measures can help us get there.”

You can reach Ben Botkin at [email protected] or via Twitter @BenBotkin1.