May 14, 2012—Residents of Cottage Grove and the surrounding area have long known that the abandoned Black Butte Mine poses dangers, but the first environmental health assessment of the mine provides concrete information.

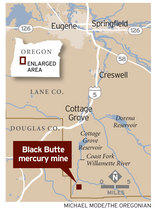

The mine, located south of Cottage Grove and near two streams that empty into the Cottage Grove Reservoir, operated from the middle of the 19th century until the 1960s. During the time it was open, it was one the most productive mercury mines in the country.

The mine, located south of Cottage Grove and near two streams that empty into the Cottage Grove Reservoir, operated from the middle of the 19th century until the 1960s. During the time it was open, it was one the most productive mercury mines in the country.

Since closing, it has sat vacant, its buildings becoming dilapidated and unmaintained. In March 2010, the federal Environmental Protection Agency deemed the mine a Superfund site. That designation required the Public Health Division to do an environmental health assessment.

Public Health Division toxicologist Todd Hudson said the assessment’s information can be used to educate the public about the mine.

“We want residents to be aware,” he said.

Lisa Arkin, the executive director of Beyond Toxics (the organization formerly known as the Oregon Toxics Alliance), thinks it’s essential for people to be educated about the mine because the Cottage Grover Reservoir is a “beautiful lake” that’s often used recreationally.

Because of the mercury in the Cottage Grove Reservoir, it’s unsafe for pregnant women, children under six, and people with liver and kidney problems to eat fish caught from the reservoir, according to the assessment, which recommends that people eat no more than one meal a month from fish in the reservoir.

The Public Health Division and the Department of Environmental Quality have determined that the source of mercury in the Cottage Grove reservoir comes from Furnace Creek, a tiny trickle of water that flows near the mine. Currently, the Oregon Public Health Division doesn’t have enough information to know if eating fish from Garoutte Creek, which also runs near the mine, should be of concern.

An advisory has been in place since 1979 to warn people about eating fish from the reservoir, which was revised in 2004. Because of the assessment’s findings, it’s not necessary to make another revision, Hudson said.

The assessment also found that the mine’s “tailings,” or rock taken out of the mine, may be contaminated with mercury and arsenic. If a toddler swallows a half teaspoon or less of those rocks, they could suffer illnesses related to arsenic or mercury poisoning — including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness and loss of concentration.

Hudson thinks it is unlikely that people will come into direct contact with the tailings, even though interviews taken as part of the assessment found that people have used the tailings in the past to fill roadbeds and driveways. “But it’s not impossible,” he said. “It’s what we call a worse

case scenario.”

The assessment recommends that the Environmental Protection Agency clean up Furnace Creek so that it no longer carries mercury to the Cottage Grove Reservoir, and that fish be tested in the creeks and rivers upstream of the reservoir for mercury levels.

Arkin is uncertain how much can be done to clean up the mine, given scarce resources. “It's not easy to clean up mines,” she said, because it’s easy for the tailings and other debris to become scattered. Unless the EPA is able to “scrap up every last speck of dirt,” she thinks the mine will continue to pose health risks. The EPA intends to do a remedial investigation of the mine, which will determine if any further

steps should be taken to make the mine safe and protect the public. Next month, the Oregon Public Health Division is planning to hold at least one public forum to discuss the assessment’s findings.

Image for this story appears courtesy of The Oregonian.