This article has been updated to incorporate additional reporting and to include a correction, below.

Gov. Tina Kotek has joined with hospitals, law enforcement and behavioral health advocates to back a legislative push to make it easier to hospitalize and forcibly treat Oregonians with severe mental illness. But some mental health consumers and the nonprofit Disability Rights Oregon say it’s a bad idea.

Like similar laws in most states, Oregon’s statute allows a judge to confine and commit someone to treatment if their mental illness makes them an “imminent” danger to themself or others.

Experts say a series of Oregon court decisions have made it far harder to commit people. Backers of the bill say this means people who need care don’t get it, with potentially fatal consequences.

Efforts to rewrite Oregon’s civil commitment law have failed in recent years. But with a high-powered coalition that includes the Oregon chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, observers say House Bill 2467 may have a better shot, especially after an amendment published Thursday tried to address some criticisms.

“When a person in a crisis doesn't receive the care that they require, it often ends in trauma, catastrophe and even crime,” First Lady Aimee Kotek Wilson, a former social worker, said in testimony in support of the bill last week. “Being able to deliver this care protects people at the most vulnerable movements in their life.”

But Disability Rights Oregon, a group funded by the federal government, is highly critical of Oregon's existing civil commitment system, calling commitment “a terrible investment” that the group says doesn't address long-term issues, can hurt outcomes and is often a “never-ending cycle of trauma” that violates the rights of vulnerable people. The group continues to oppose the bill despite the amendment.

“The changes proposed today to the statute are simultaneously the most expensive and least viable options,” Dave Boyer, managing attorney of Disability Rights Oregon’s Mental Health Rights Project told The Lund Report in a statement last week. “They won’t help individuals in crisis or people who care about them, but they will further burden our already overtaxed system and waste limited resources.”

The bill would broaden the civil commitment criteria, allowing a judge to involuntarily hospitalize someone if they are deemed “likely to inflict significant physical harm” to themself or others within the next 30 days. The judge could also consider a person’s past suicide attempts and “patterns of deterioration” that contributed to them being hospitalized for psychiatric care.

“We know firsthand what it takes to foster a pathway of recovery and healing. And from our experiences, we believe it almost never begins with involuntary treatment.”

The amendment to the bill would also take into account the “person’s particular history and circumstances” and whether they are likely to become dangerous or unable to take care of their basic needs without treatment.

Chris Bouneff, executive director of Oregon NAMI, told The Lund Report that his group, which spearheaded the bill, crafted the amendment to address criticisms and other input. He disagrees with Disability Rights Oregon's critique.

“We weren’t throwing the barn door open for civil commitment,” he said.

He is optimistic some version of the bill will pass this session. A spokesperson for Kotek told The Lund Report that the governor supports the amended language.

The Oregon House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the bill Thursday and is scheduled to vote on it Tuesday.

Civil commitments dropped as civil commitment petitions grew

Oregon lawmakers have poured money into the state’s behavioral system in recent years. Despite their efforts, the state faces a potential contempt order from a federal judge over Oregon State Hospital overcrowding and lack of mental health treatment, which could force more spending.

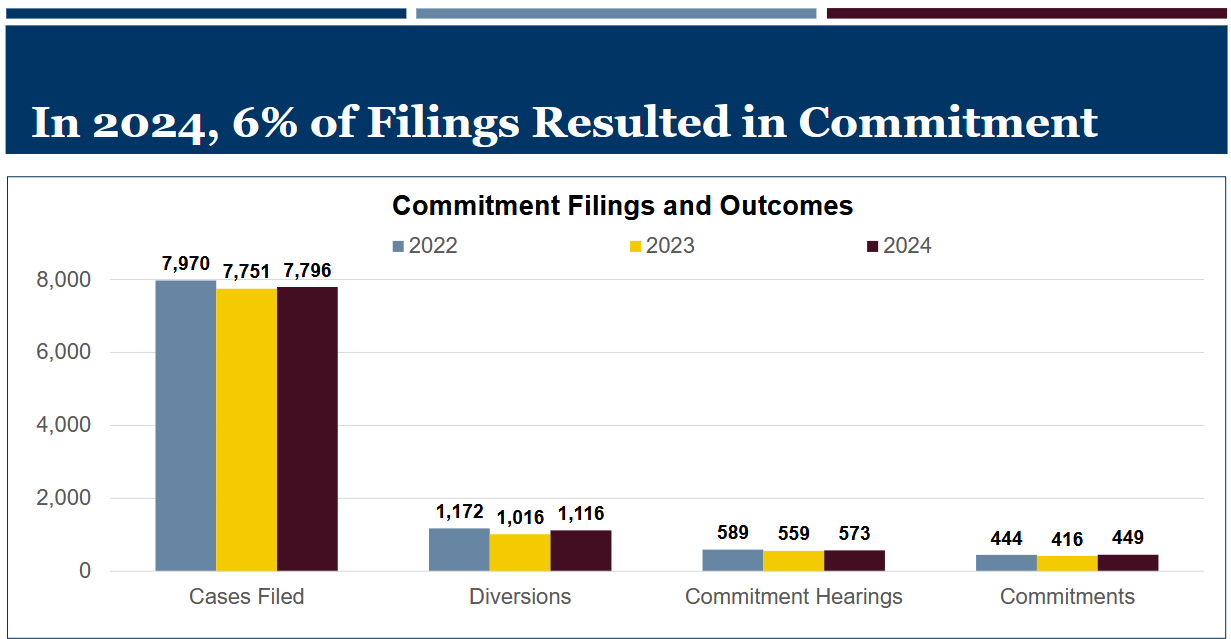

Over time, research shows, the number of civil commitment petitions has grown significantly even as the number of people committed has shrunk. Last year, 6% of roughly 7,800 civil commitment cases resulted in a commitment, which is about the same percentage as the last two years.

In addition to law enforcement groups and the Oregon Psychiatric Physicians Association, Central City Concern and Cascadia Health, two large Portland area social service providers, also support the bill.

But mental health consumers and their advocates have joined Disability Rights Oregon in opposing the bill.

David Oaks is the co-founder of Eugene-based MindFreedom International, underwent forced treatment in the 1970s. He told The Lund Report the bill takes a “crystal ball approach” that tries to predict how dangerous someone is and “directly contradicts the American justice system’s values.”

Oaks said he understands the frustrations around the state’s behavioral health system. But he and others say the focus should be on other solutions.

Hearing shows divide

The longstanding divide on the issue was on display during the legislative hearing on the bill last week.

“The question today isn’t whether Oregon should commit people,” Bouneff told lawmakers. “It already is doing so. Only we are waiting for people with severe symptoms to be arrested and then compelling them into care.”

Bouneff said his group’s helpline counsels desperate families that they have the choice of watching a loved one deteriorate or calling 911 and hoping they get care after being arrested. However, he said that care is only intended to make someone well enough to face prosecution.

“She was harmed so much by her treatment that when she finally got to living home with us, her family, she was just a shadow of herself."

Dr. Andy Mendenhall, CEO of Central City Concern, told lawmakers that the “vague” civil commitment standard is making it difficult for his organization to provide housing or other services to people experiencing psychosis.

Leading up to the incident, the couple watched their son become paranoid, disoriented and “disconnected from reality,” he said. They called the mobile crisis and pleaded with police for help, he said. But he said their hands were tied by the law.

“You should not have to kill your mom to get mental health treatment,” he said.

KC LeDell, the governor’s senior behavioral health policy advisor, told lawmakers that the problem with the civil commitment process is that it requires a judge to determine that someone “will harm themselves or others within minutes or hours.” If someone is held in jail, there is a presumption that their needs are being met, he said, making it harder to commit them.

“We weren’t throwing the barn door open for civil commitment."

The bill’s amendment would allow someone to be committed if it is “reasonably foreseeable” they will harm themselves or others but harm is not imminent. LeDell said this is intended to strike a “careful balance.”

“We do not want people committed based on speculative harm in the distant future, but we also do not want to have to wait to commit people until the absolute last minute,” he said. “If commitment is only available to those on the very brink of disaster, it will fail to catch the people before they go over the edge.”

Civil commitment no panacea, critics say

Others disagreed. One woman told lawmakers that her daughter was civilly committed 12 times in Oregon, undergoing forced injections and being put on powerful antipsychotics that caused cognitive impairment and her mobility.

“She was harmed so much by her treatment that when she finally got to living home with us, her family, she was just a shadow of herself,” the woman said.

Members of the Oregon Consumer Advisory Council, a state advisory panel, submitted testimony on the bill asking lawmakers to consider other options.

They cited state figures showing it costs $32 million to forcibly commit 100 people for 180 days. They argued that money would be better spent on mobile crisis units, behavioral health supports, teaching kids about emotional wellness and peer support programs.

“We know firsthand what it takes to foster a pathway of recovery and healing,” the council members wrote.” And from our experiences, we believe it almost never begins with involuntary treatment.”

“You should not have to kill your mom to get mental health treatment.”

Bob Joondeph, the former longtime leader of Disability Rights Oregon, wrote in his testimony that the bill only addresses one part of the problem and urged lawmakers to devote more resources to mental health services.

To that end, Bouneff said during the hearing that NAMI is backing companion legislation. Senate Bill 1195 a similar bill in the House, HB 2015, are intended to open up space in residential treatment facilities by changing state regulations.

A pending amendment to another related bill, HB 2059, would direct $90 million to establishing additional residential treatment facilities.

(Nick Budnick contributed reporting.)

Correction: An earlier version of this article inaccurately attributed testimony during the legislative hearing. The Lund Report regrets the error.

You can reach Jake Thomas at [email protected] or at @jthomasreports on X.

Thanks for this report, Lund. I was at the Thursday, 4/3, hearing and over decades I have attended more than a dozen legislative hearings, but I was surprised at how unfair Rep. Kropf chaired the meeting. Even though he knew he had a lot of folks wanting to testify, for the first few panels he had no time limit. All of the testimonies were in support.

The very moment that a panel opposed the bill, Rep. Kropf began timing. Especially sad was that until then we had not heard from direct lived experience of involuntary mental health care.

It is very revealing that the Governor and the Committee that formed the bill, totally ignored any input from the main advisory panel in Oregon for lived experience, the Oregon Consumer Advisory Council.

So much of the deeper story was ignored that day, and in general in our society. For those interested in fighting this bill, I recommend contacting MindFreedom based in Eugene.