In early December, executives at Bay Area Hospital in Coos Bay received the official notification from outside auditors that every health care leader dreads: The hospital was in such poor financial shape that there was “substantial doubt about its ability to continue as a going concern,” the auditors wrote.

The 172-bed hospital — the largest on the Oregon Coast — was, and remains, in a deep financial swamp, likely the worst of any hospital in the state.

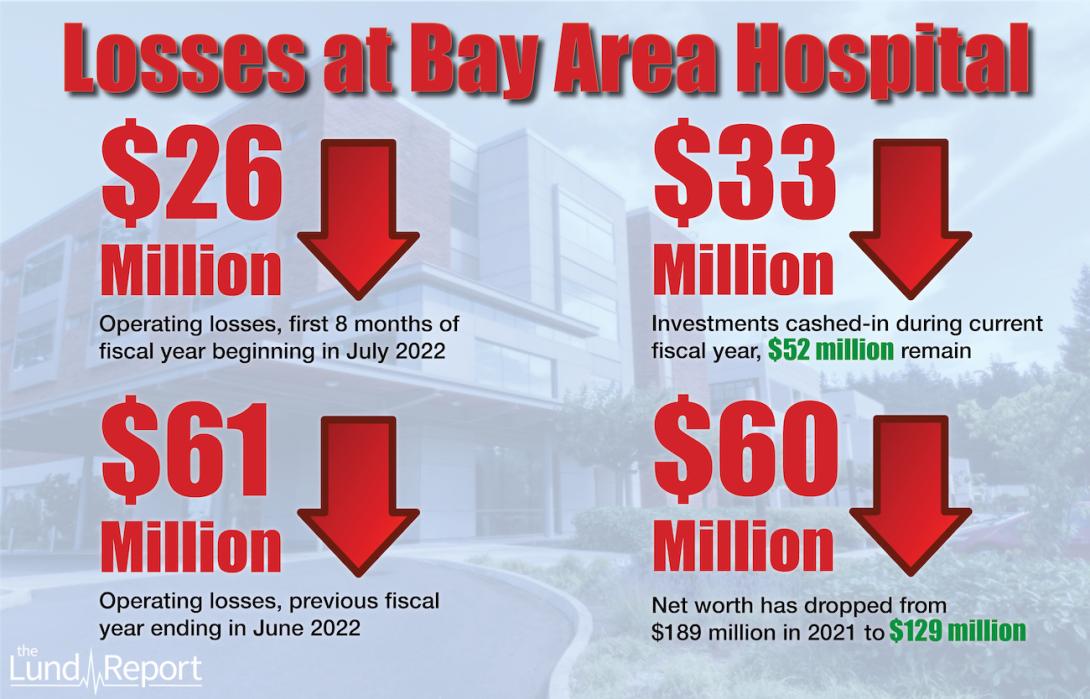

Battling soaring COVID-19-related costs as well as foul-ups in the hospital’s patient and insurance billing computer system, the hospital racked up a staggering $61 million loss in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2022. That put the cash-strapped hospital in violation of the terms of its $47 million loan from Bank of the West. And that meant the bank could demand immediate repayment.

“If Bank of the West did call the note due and payable, which is in their legal right, the hospital probably would not survive that call.”

“If Bank of the West did call the note due and payable, which is in their legal right, the hospital probably would not survive that call,” said Chief Financial Officer Mary Lou Tate in a recent interview with The Lund Report.

The bank hasn’t demanded repayment — although it did nearly double the loan’s interest rate, to 4.5%. The hospital, with the help of outside consultants, is working on a turnaround plan — and updates bank officials weekly. Operating losses persist — $26 million on revenues of $130 million in the eight months through February, the hospital’s finance reports show. But the hospital’s goal is to boost revenues, curb expenses and claw its way to a break-even point in 18 to 24 months, Tate said. It hopes to eke out a small profit after that, she said.

Hospital systems are reporting financial woes around the state: quarter after quarter of operating losses, soaring employee costs, Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements that don’t cover expenses, credit downgrades by bond rating agencies. Last week, the trade group representing Oregon hospitals issued a financial report calling 2022 “one of the worst” years for hospitals since 1993.

But Bay Area Hospital appears to be in a class of its own, with a staggering array of financial difficulties.

The 1,100-employee hospital’s struggle is important. Set in the heart of the city of Coos Bay, the facility draws patients from a 150-mile span stretching from Florence to the California border. In an era when large for-profit and non-profit hospital chains increasingly dominate health care, Bay Area Hospital is an anomaly. It’s a standalone, independent facility; a hospital district that is officially a local government entity. It is legally able to levy property taxes — if voters approve. But it has not done so for nearly 40 years. More than most Oregon hospitals, its patients are overwhelmingly elderly and on Medicare or lower-income and on Medicaid. The hospital is heavily unionized, and management-union relations have been testy.

The hospital’s trouble with its bank loan seems to be unique in the state. It appears to be the only Oregon hospital whose financial condition is so weak — especially its ratio of cash flow to debt — that it is in violation of its borrowing agreement, is technically in default and lacks the cash to pay off its loan. During 2022, some other financially troubled Oregon hospitals may have fallen out of compliance with their bond or bank loan agreements, or renegotiated them, but they are financially stronger than Bay Area Hospital. For example, since September the Portland-based Legacy Health hospital system has failed to meet some loan terms and has received waivers from lenders, but it has ample cash on hand to pay off the debt if need be, according to the Moody’s bond rating service. Moody’s kept Legacy’s bond rating at A1, but downgraded its outlook to “negative.”

To stay afloat, Bay Area Hospital is open to all options, including merging into a chain or seeking a tax levy, Tate said.

“Nothing is off the table, but no decisions have been made about what the future needs to look like,” she said. “We are committed to make sure that we are here, but it might not look the same as it has in the past.”

The hospital is focused on surviving, said Dr. Tom McAndrew, chair of the board of directors. “Next year, the hospital celebrates its 50th year in the community, and we’re doing everything in our power to be here for the next 50, for this community,” he told The Lund Report.

Coos Bay Mayor Joe Benetti said the hospital is a vital presence. A handful of tiny hospitals dot the south Oregon Coast. These include the16-bed Lower Umpqua Hospital in Reedsport, the 25-bed Coquille Valley Hospital in Coquille, and the 21-bed Southern Coos Hospital in Bandon. All three are public hospital districts partly supported by property taxes. The Bay Area Hospital “helps serve the other hospitals. It provides services that the others do not offer,” Benetti said.

Benetti said he meets monthly with the hospital’s executives for updates. “Unfortunately, they are going through difficult times,” he said.

Never very profitable

Even during the best of financial times for Oregon hospitals — the boom years from the expansion of Medicaid coverage in 2014 to the onset of the pandemic in 2020, Bay Area Hospital was only modestly profitable. In its fiscal year ended June 2019, the hospital had an operating profit margin of 3.5% — $6.5 million on revenues of $187 million. By contrast, many big Oregon hospitals had profit margins in the double digits, or high single digits that year.

With the onset of the pandemic, the hospital barely broke even in the fiscal year ending June 2020, then reported a $10 million operating loss the following fiscal year, capped by the $61 million loss on operating revenues of $182 million.

Some unusual chronic factors have driven the hospital’s historically tight finances.

Only about 17% of the hospital’s patients are covered by commercial insurance, Tate said. Almost all the rest are covered by Medicaid or Medicare. That reflects the demographics of the service area, which is lower-income and elderly. And it is a significant drawback: commercial insurance typically pays much higher reimbursement rates than Medicaid and Medicare. Many major Oregon hospitals, in more prosperous metro areas, have a patient mix with 40% or more covered by commercial insurance. That’s a big driver of their profitability.

A second limitation, said Tate, is that as a government entity, the hospital is legally barred from investing in the stock market or higher-risk bond markets. Instead, it is confined to investing in low-return high-security bonds or mortgage-backed securities. “The rate of return is very small,” Tate said.

As a result, its investment portfolio has been relatively stagnant, while large nonprofit hospital systems, with heavy investments in the stock market and riskier bonds, saw their portfolios leap during the long boom in financial markets after the Great Recession. Heading into its crisis last year, Bay Area Hospital had an investment portfolio of $87 million. But as revenues drooped and expenses rose, the hospital cashed in $33 million of its investments to pay its bills. The portfolio now stands at $52 million.

Labor strife

Nor is the hospital exempt from the labor contract-negotiation friction that has made headlines at other Oregon hospitals. The hospital’s workers have won big pay hikes — which in the short run make it all the more difficult for the hospital to break even.

After a year of increasingly bitter haggling, the hospital and the United Food & Commercial Workers union recently agreed on a three-year contract that sharply boosts wages for the roughly 500 represented workers at the hospital. The deal gives an upfront 7.5% pay raise to all workers, with some jobs getting up to 25%, plus raises in the two following years of up to 7% a year, depending on inflation, plus annual step increases of up to 3%, according to hospital spokesperson Kimberly Winker.

The union is jubilant. “We are proud of our members for standing together and advocating for their rights,” said local union president Dan Clay. “Together, they were able to push Bay Area Hospital into an agreement that we are proud of.”

That deal followed on the heels of a new three-year contract last year with the hospital’s 250 nurses, which provided an immediate raise averaging about 10%, to be followed by annual raises of up to 4%, depending on inflation, as well as annual step increases of about 2.5%. The hospital and the Oregon Nurses Association negotiated for nearly a year.

The hospital needs to pay competitive wages if it wants to find and keep workers, stressed Tate, an experienced health care finance executive who joined Bay Area Hospital last August. “Many of our employees were not being paid fair market wages,” she said. Pay had fallen behind due to the wage inflation that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic, she said. “We did have to come to the table with a larger than normal settlement to get our employees up to fair market wages,” she said.

“Initially the expenses go up, but the plan is when you are paying a fair market wage you are not losing employees,” and can cut the use of extremely expensive temporary contract workers, she said.

Lenders are leery

Virtually all Oregon hospitals take on debt through bank loans or bonds, but Bay Area Hospital’s debt has become an uncommonly big thorn. Financial records show the hospital began falling out of compliance with its Bank of the West loan agreement in the spring of 2022, when cash flow sagged and operating losses rose. Since then, the bank, owned by Canada-based BMO, has signed short-term temporary agreements with the hospital promising not to foreclose on the loan, Tate said. The hospital is now negotiating with the bank for a longer forbearance agreement, she said.

“They are working with the hospital because they understand that to call the note would be devastating to the hospital,” she said.

The hospital has searched for a new lender willing to step in and replace Bank of the West, but to no avail. It has approached at least seven other lenders, finance committee records show. Only one expressed interest, and it wanted an interest rate of 12%-15%, the records show.

“They don’t necessarily have the appetite, with us being in forbearance and in default with the current lender. It makes finding a new one very difficult,” Tate said.

The hospital’s net worth — all assets minus all liabilities — stands at $128 million, about the value of its $52 million investment portfolio plus the buildings and equipment. Theoretically, the hospital might be able to pay off the Bank of the West loan by cashing in all its investments. But that would leave the hospital with a perilously thin cash cushion to handle any large rises in monthly expenses or delays in insurance reimbursements.

“You would have to have very quick cash turnaround. Very quickly you would be running out of cash,” Tate said.

Billing losses

Like many hospitals, Bay Area Hospital has been upgrading its computer systems. But the hospital faced an extraordinary problem in 2021-22 with its transition to new technology for billing insurers and patients.

The hospital launched the billing switchover in mid-2021, and glitches quickly led to the hospital not sending bills out on time, according to the annual audit. Under typical insurance contracts, providers must bill promptly or the insurer can refuse to pay. The billing failures persisted for many months. The hospital ended up forfeiting about $18 million in lost billings, Tate said. It can’t recover that money.

That loss, combined with COVID-19-related revenue declines and soaring costs for temporary contract workers created the $61 million operating loss in the 12 months ended June 2022 that plunged the hospital into its current debt crisis, according to the audit.

It’s unclear how aware the Coos Bay community is of the problems of the hospital. Some members of the public attend the monthly finance committee meetings, and hospital employees are paying attention.

“We’re working to make sure the community is aware of the financial concerns of the hospital, but not to the point where they are panicking,” Tate said.

The hospital “has always been very proud that they don’t receive (property) taxes,” said Mayor Benetti. But a tax levy “is something they should think about. Voters might be receptive if it is tied to providing specific services.”

Fixes slow to come

Like other hospitals trying to emerge from COVID-19, Bay Area Hospital is finding that fixes aren’t quick or easy.

One unusual step is asking commercial insurers to increase their reimbursement rates. The hospital has submitted proposals to seven commercial insurers, and one has made a counter-offer, according to finance committee records. Commercial insurers typically lock in multi-year rate contracts with providers such as hospitals, and getting insurers to agree to raise rates mid-stream is not easy.

The hospital is also working with insurers to smooth out kinks in the reimbursement flow to make sure sorely needed money arrives as quickly as possible, Tate said.

Bay Area Hospital suffered a sharp drop in elective surgeries during the pandemic. Surgeries remain below pre-COVID-19 levels. Eye surgeries at the hospital are still low and surgeries overall are hampered by a lack of anesthesiologists, according to finance committee reports. Lab, cardiology and emergency department usages are also low. But in the last few months, surgeries and overall hospital usage appear to be stabilizing or even rising a bit, the reports said. Meanwhile, employee costs continue to push upward, and the hospital still relies heavily on expensive contract workers. But contract labor costs “are beginning to show a slight downward trend,” the most recent report said.

The hospital’s plan for getting to breakeven involves boosting revenues by about $22 million and slicing expenses by about $12 million.

Tate said the hospital wants eventually to reach an operating profit margin of 3%-5%. “That would be a good spot to be at,” she said. “But it will be very challenging to get into that range.”

I have lived in Coos Bay for some 38 years and was sad but unsurprised to learn of the dire financial straits that BAH finds itself navigating. First, as a former reporter for a Portland daily (in the ‘70s) I want to offer kudos to you for some real journalism, an excellent article both well written and very timely. Our local rag sadly has had nothing to say on the subject but perhaps they will rewrite yours since it certainly is a matter of great concern to our community.

In addition to the deserved praise above, there is one point of great importance that you did not cover and that concerns the hospital’s spending history in re: massively overambitious spending on capital improvements over years but especially some 10 years ago that directly https://www.hoffmancorp.com/project/bay-area-hospital-expansion/ relates, imo, to the financial hot water BAH finds itself swimming in. It would be good if some light could be shed on this aspect if you end up doing any sort of followup story since the magnitude of the crisis, again imo, would not be as severe as it is if far more modest and appropriate improvements had been made.

Again, thanks for a great story — very much needed coverage!