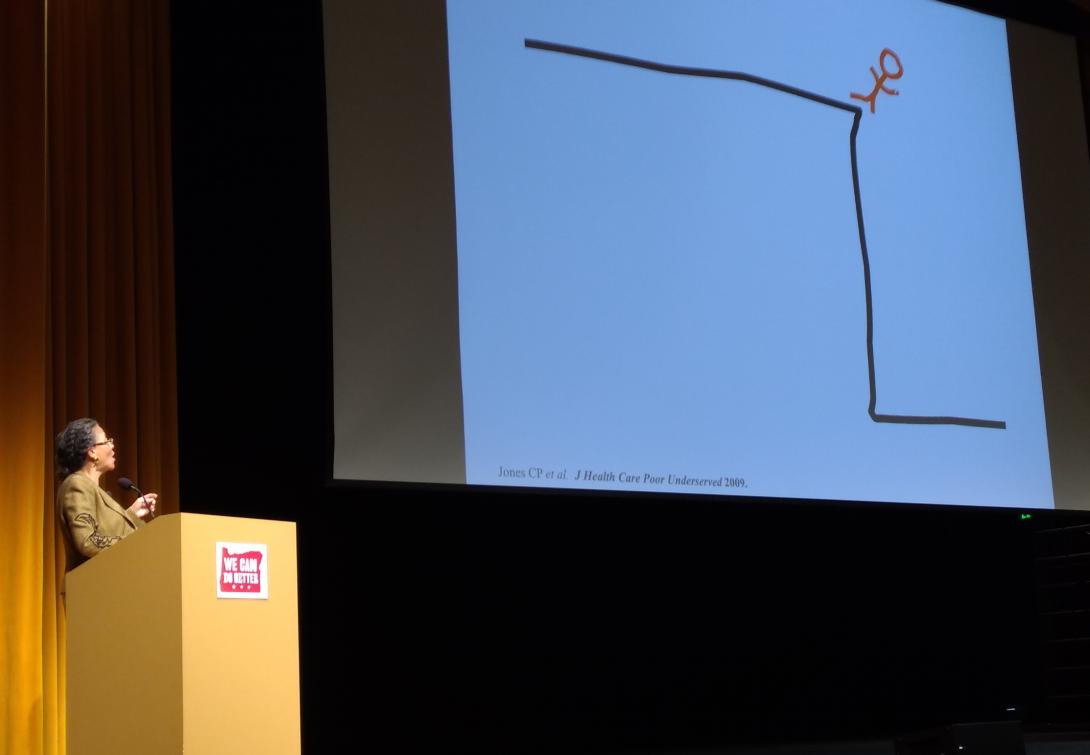

Dr. Camara Jones flashed a childlike diagram on the big screen in a Portland Art Museum auditorium. It depicted six orange and green stick people on a cliff. The three in the orange group were well away from the edge, and a fence shielded them from falling over. The greenies, as she called them, were up against an edge. Nothing protected them from a free fall to the bottom, where an ambulance was parked.

That, Jones said, illustrates racial disparities in health in the United States.

Jones, a medical doctor with a master’s of public health and doctorate and a senior fellow at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute and Cardiovascular Research Institute, addressed several hundred people on Thursday at the annual conference of the group, We Can Do Better, an advocacy organization that works for better health care for all. Jones is an expert in the racial inequities in health care, a lead topic of the conference and one that’s considered a priority for Oregon Gov. Kate Brown and the Oregon Health Authority, which administers the state’s $6 billion Medicaid program, Oregon Health Plan.

Racial barriers to health care have been documented in numerous studies and dating back years. In 2002, the Institutes of Health released a report requested by Congress that examined a range of studies looking at racial disparities in health care. It found that people of color receive lower quality of care, even when insurance status, income, age and the severity of the condition are the same.

Though there’s now more awareness of the problem, it continues to plague the health-care industry. A recent Oregon study showed that that white people received better care from emergency medical technicians than people of color.

Racism is alive, Jones said, when asked by an audience member why everyone is always talking about race. Just look at recent cases of police brutality against black people, Jones said, naming a number of case, including Jermaine Massey, who was kicked out of the DoubleTree hotel in the Lloyd District in December for simply being a black guest talking to his mother in the lobby.

Her stick people illustration aimed to show how some communities end up closer to the edge and others experience a privileged distance. But she said that was only part of the story.

“As useful as this diagram is in starting conversations,” Jones said, “it has a huge fatal flaw. It does not equip us to talk about how health disparities arise."

Inequities in health care are systematic, she said. It starts with who’s invited to the table, what’s on the agenda and who makes the decisions and who doesn’t. She said racism is engrained in the system and that people don’t even recognize there’s a problem until someone falls off the cliff.

She cited three main reasons for that: a focus on the individual rather than the entire community, a lack of awareness of history and the myth that if you work hard enough, you will succeed.

“When we do not acknowledge the unevenness of the playing field, we are complacent to the myth of meritocracy,” Jones said.

In drawing a picture of how racism operates and perpetuates, Jones cited an allegory of a gardener who prefers red flowers over pink ones. That gardener has two pots. One has rich soil, the other has poor soil. Preferring red flowers, she plants those seeds in the rich soil. She puts the pink flower seeds in the other pot. The red flowers blossom beautifully but the pink plants turn out spindly. The gardener feels justified in her preference for red flowers. She replants the seeds from the two plants in similar pots and, as before, on thrives, one does not. The gardener’s children also develop a preference for red flowers. They think pink ones are inferior.

And so the cycle is repeated and it seems as if this is how things must be. No one considers the history of the soil.

Jones said that society needs to start focusing on effective interventions to break the cycle.

“We need to be thinking of investing in opportunity instead of counting outcomes,” Jones said.

That requires patience and a realization that change could come in 20 years.

“We have to push the agenda and see how it shakes out,” Jones said. “If something is important for society, then society will pay for it.”

She said that the current system that assigns opportunity to people depending on how they look unfairly disadvantages some individuals, gives others an unfair advantage and saps the strength of the entire society by wasting human potential.

Everyone has something of value to offer, she said, urging the audience to take an active role in change.

“There is a lot of work to get high-quality access to health care,” Jones said. “We need to join the rest of the world. That’s how a civilized society values its society.”

Her words resonated with the audience, which jumped to its feet and gave her a standing ovation.

“I think her brilliance and compassionate commentary were particularly poignant and relevant in this time, really brings into focus the causes and costs of racism in American, the most pressing and globally confounding issue in our nation and world today,” said Leslie Gregory, a Portland physician assistant and founder of the nonprofit, Right To Health, Inc.

You can reach Lynne Terry at [email protected].